|

|

|  As this striking animation shows,

China's 15th-century "treasure junks" would have dwarfed European

vessels of the time.

As this striking animation shows,

China's 15th-century "treasure junks" would have dwarfed European

vessels of the time.

View the clip in:

QuickTime | RealVideo:

dialup |

broadband

Get video software:

QuickTime |

RealVideo

|

Ancient Chinese Explorers

by Evan Hadingham

In 1999, New York Times journalist Nicholas D. Kristof reported a

surprising encounter on a tiny African island called Pate, just off the coast

of Kenya. Here, in a village of stone huts set amongst dense mangrove trees,

Kristof met a number of elderly men who told him that they were descendants of

Chinese sailors, shipwrecked on Pate many centuries ago. Their ancestors had

traded with the local Africans, who had given them giraffes to take back to

China; then their boat was driven onto the nearby reef. Kristof noted many

clues that seemed to confirm the islanders' tale, including their vaguely Asian

appearance and the presence of antique porcelain heirlooms in their

homes.

If Kristof's supposition is correct, then this remote African outpost retains

an echo of one of history's most astonishing episodes of maritime exploration.

Six centuries ago, a mighty armada of Chinese ships crossed the China Sea, then

ventured west to Ceylon, Arabia, and East Africa. The fleet consisted of giant

nine-masted junks, escorted by dozens of supply ships, water tankers,

transports for cavalry horses, and patrol boats. The armada's crew totaled more

than 27,000 sailors and soldiers. The largest of the junks were said to be over

400 feet long and 150 feet wide. (The Santa Maria, Columbus's largest

ship, was a mere 90 by 30 feet and his crew numbered only 90.)

Loaded with Chinese silk, porcelain, and lacquerware, the junks visited ports

around the Indian Ocean. Here, Arab and African merchants exchanged the spices,

ivory, medicines, rare woods, and pearls so eagerly sought by the Chinese

imperial court.

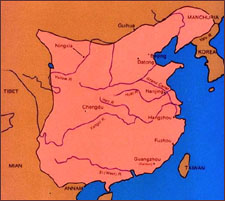

Seven times, from 1405 to 1433, the treasure fleets set off for the unknown.

These seven great expeditions brought a vast web of trading links—from

Taiwan to the Persian Gulf—under Chinese imperial control. This took place

half a century before the first Europeans, rounding the tip of Africa in frail

Portuguese caravels, 'discovered' the Indian Ocean.

Despite the strength and prosperity that marked their empire, Ming

emperors deliberately chose not to try to colonize lands beyond the Middle

Kingdom.

Despite the strength and prosperity that marked their empire, Ming

emperors deliberately chose not to try to colonize lands beyond the Middle

Kingdom.

|

|

With unrivaled nautical technology and countless other inventions to their

credit, the Chinese were now poised to expand their influence beyond India and

Africa. Here was one of history's great turning points. Had the Chinese

emperors continued their huge investments in the treasure fleets, there is

little reason why they, rather than the Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch and British,

should not have colonized the world. Yet less than a century later, all

overseas trade was banned, and it became a capital offense to set sail from

China in a multi-masted ship. What explains this astonishing reversal of policy?

Roots of Chinese seapower

The first Chinese oceangoing trade ships were built far back in the Song dynasty

(c. 960-1270). But it was the subsequent Mongol emperors (the Yuan dynasty of

c. 1271-1368) who commissioned the first imperial treasure fleets and founded

trading posts in Sumatra, Ceylon, and southern India. When Marco Polo made his

famous journey to the Mongol court, he described four-masted junks with 60

individual cabins for merchants, watertight bulkheads, and crews of up to 300.

When the Han Chinese overthrew the Mongols and founded the Ming dynasty in the

later 14th century, they took over the fleet and an already extensive trade

network. The enterprising spirit of the Ming era reached a climax following the

rebellion of the warrior prince Zhu Di, who usurped the throne in 1402.

Disapproved of by the Confucian "establishment," Zhu Di put his trust in the

worldly eunuchs who had always sought their fortunes in commerce. During his

revolt, Zhu Di's right-hand man had been the Muslim eunuch Zheng He, whom he

now appointed to command the treasure fleet.

At the start of the first of Zheng He's epic voyages in 1403, it is said that

317 ships gathered in the port of Nanjing. As sociologist Janet Abu-Lughod

notes, "The impressive show of force that paraded around the Indian Ocean

during the first three decades of the 15th century was intended to signal the

'barbarian nations' that China had reassumed her rightful place in the

firmament of nations—had once again become the 'Middle Kingdom' of the

world."

|  Zheng He's

ships, as depicted in a Chinese woodblock print thought to date to the early

17th century.

Zheng He's

ships, as depicted in a Chinese woodblock print thought to date to the early

17th century.

|

Treasure junks: fact or fiction?

The Ming account of the voyages that followed strains credulity: "The ships which

sail the Southern Sea are like houses. When their sails are spread they are

like great clouds in the sky." Were the reported dimensions of the biggest

galleons—over 400 feet long by 150 wide—gross exaggerations? If accurate,

these dimensions would signal the biggest wooden ships ever built. Only the

mightiest wooden warships of the Victorian age approached these lengths, and

several of these vessels suffered from structural problems that required

extensive internal iron supports to hold the hull together. No such structures

are reported in the Chinese sources.

However, in 1962, the rudderpost of a treasure ship was excavated in the ruins

of one of the Ming boatyards in Nanjing. This timber was no less than 36 feet long.

Reverse engineering using the proportions typical of a traditional junk

indicated a hull length of around 500 feet.

Unfortunately, other archeological traces of this "golden age" of Chinese

seafaring remain elusive. One of the most intensively studied wrecks, found at

Quanzhou in 1973, dates from the earlier Song period; this substantial

double-masted ship probably sank sometime in the 1270's. Its V-shaped hull is

framed around a pine keel over 100 feet long and covered with a double layer of

intricately fitted cedar planking, thus clearly indicating its oceangoing

character. Inside, 13 compartments held the residue of an exotic cargo of

spices, shells, and fragrant woods, much of it originating in east Africa (see

Asia's Undersea Archeology).

The Quanzhou wreck suggests that over a century before Zheng He's fabled

voyages, the Chinese were already involved in ambitious trading exploits across

the Indian Ocean. Even back then, their sturdy ships equaled the largest known

European vessels of the period. By inventing watertight compartments and

efficient 'lugsails' that enabled them to steer close to the wind, Chinese

shipbuilders remained ahead of the west in the following centuries.

Continue: Exploits of the eunuch admiral

On China's China |

Ancient Chinese Explorers

Asia's Undersea Archeology |

Date the Dish |

Resources

Transcript |

Site Map |

Sultan's Lost Treasure Home

Editor's Picks |

Previous Sites |

Join Us/E-mail |

TV/Web Schedule |

About NOVA

Watch NOVAs online |

Teachers |

Site Map |

Shop |

Search |

To Print

PBS Online |

NOVA Online |

WGBH

© | Updated April 2003

|

|

|