|

|

|  Tung Wu is author of Tales from the Land of Dragons:

1,000 Years of Chinese Painting. He has been at Boston's

Museum of Fine Arts since 1971.

Tung Wu is author of Tales from the Land of Dragons:

1,000 Years of Chinese Painting. He has been at Boston's

Museum of Fine Arts since 1971.

|

On China's China

For many centuries China held the secret to making the world's finest porcelain—white, translucent ceramic ware of such high quality that it produced a

musical tone when struck. The envy of potters and collectors in Europe and the

Middle East, Chinese blue-and-white porcelain owed its excellence to the fine

clay available to the Chinese as well as to their high-temperature kilns and

the cobalt pigment they used to produce the pieces' brilliant hues. Here,

Tung Wu, Head of the Department of Art of Asia, Oceania, and Africa at Boston's

Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) and consultant for the NOVA program

"Sultan's Lost Treasure," reveals some of the

carefully held secrets of early Chinese porcelain-makers.

NOVA: As a curator of Asian art, you must have a keen interest in Chinese

ceramics and in Chinese porcelain. What is it that makes Chinese porcelain so

special?

Wu: It is quite remarkable that ceramic art in China is the longest,

continuously evolving art form, which dates all the way back to 7,000 B.C. No

wonder we call porcelain "china," because it's perhaps China's most significant

contribution to world culture and art. The Chinese started with earthenware, as

did many others, but then moved to stoneware very early on, I think about the

12th or 11th century B.C., with added alkaline glaze to enhance the beauty of

stoneware. And further on, about the 8th century A.D., they had a prototype of

porcelain in the making.

By the Sung Dynasty, 12th century A.D., the Chinese had totally mastered the

art of porcelain. But it wasn't really until the Mongolians, who conquered

China as well as the Eurasian continent, came on the scene that Chinese

porcelain became widely known to people outside of China. The Mongolians were

not only conquerors but also able traders. They were the ones who brought the

cobalt material [blue pigment] from Iraq and Iran all the way to China to

decorate blue-and-white porcelain. Then they turned around and exported such

new wares to the Near East for a huge profit.

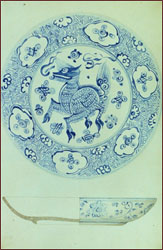

The body of Chinese blue-and-white porcelain is made from a

fine, white clay. The blue designs are painted on the piece

before it is fired in the kiln.

The body of Chinese blue-and-white porcelain is made from a

fine, white clay. The blue designs are painted on the piece

before it is fired in the kiln.

|

|

NOVA: I understand that people in Europe and the Middle East tried to duplicate

the porcelain art. What happened?

Wu: They all tried very hard but were not successful at first. Their kiln

temperatures were only high enough to create earthenware, not porcelain, and

their clay was not the same white porcelain clay as that from China. Though in

appearance such copies may resemble Chinese porcelain, their clay bodies are

merely as hard as earthenware. The Boston museum has a number of outstanding

Islamic copies that can be compared with those Chinese porcelain pieces.

NOVA: What made the white of the Chinese porcelain so pure?

Wu: The Chinese had a special type of kaolin clay with very low iron content.

After further refinement, the clay appeared rather white.

NOVA: And what makes Chinese porcelain so durable?

Wu: There are two conditions that contribute to porcelain's durability: the

tense physical structure and chemical composition of kaolin clay, which is a

local white clay from Jingdezhen, the great ceramic center in south-central

China, and the high firing technique adopted by potters to fuse kaolin clay and

china stone with a translucent alkaline glaze into forming a crystallized hard

porcelain body.

|  This bowl, retrieved during the excavation covered in the

NOVA program, is an example of porcelain produced for export.

This bowl, retrieved during the excavation covered in the

NOVA program, is an example of porcelain produced for export.

|

NOVA: Can you explain the differences between porcelain produced for imperial

use and porcelain made for export?

Wu: The court-commissioned porcelains, so-called Imperial porcelain, are of the

highest quality. The potters would throw out anything with imperfections and

submit only perfect ones to the court. Therefore, when you say it's court

porcelain, that implies quality and rarity, and therefore high value.

NOVA: And the porcelain made for export?

Wu: As for the Chinese export porcelains, the quality could be mixed. It could

be very high, only one level below the imperial ones. Or it could be very

coarse and ordinary, and the resulting porcelain inexpensive, depending upon

which group of consumers they were marketing for. The Japanese tea masters in

the 17th century, for example, commissioned Jingdezhen potters to make tea

porcelains in Japanese taste. These pieces needed to be styled a little

asymmetrically rather than perfectly, because Japanese preferred the aesthetic

of imperfection. The Jingdezhen potters would try hard to comply and make a

perfect one imperfect. Such tea utensils were often of high quality, with

unique decorations. These are still treasured by the Japanese tea community

today. Other high-quality porcelain wares are those exported to Europe in the

16th and 17th centuries. Again, they were made according to European tastes in

terms of shapes and designs.

Chinese porcelains were also exported to Chinese communities throughout

Southeast Asian countries, because overseas Chinese had great demands for

Chinese porcelain as well. Such works could be of mediocre quality, since they

were intended for daily usage rather than for display purpose.

NOVA: Is it true that porcelain made for export didn't have reign marks and

other types of marks?

Wu: In general, yes, because export porcelains were not supposed to have such

reign marks, simply because they were not made for the court consumption.

However, some commercial potters would add some kind of marks, but not quite

the same as the reign marks, in order to increase the value of their export

pieces. For example, the standard court mark would read "made during the Xuande

era of the great Ming Dynasty." A commercial potter would make a mark that just

read "made during the great Ming period," without including the reign name—"in the Xuande era." In the MFA's collection is a lovely 16th-century Chinese

blue-and-white wine ewer discovered in Indonesia. The ewer bears a simplified

and sketchy four-character mark reading "Made in the Zhengde era."

NOVA: I understand that quality and intensity of the blue pigment used in

blue-and-white porcelain changed over time.

Wu: Yes, the cobalt the Chinese potters first encountered in the late Yuan to

early Ming period (14th century) was imported from the Near East. Its cobalt

was a type with an arsenic impurity. The mixture of arsenic and cobalt seemed

to intensify that blue color after high firing. The Chinese call such a rich,

dense, deep blue color "Huihuiqing" or Muhammadan blue.

Later in the late 15th century, the Chinese discovered cobalt in their own

country, which is a kind of cobalt with a manganese mixture. The manganese

tended to make the blue color lighter, less intense than the imported cobalt.

Afterward, in the second half of the 17th century, Chinese potters learned to

combine the lighter and richer cobalt colors to create more vivid and dramatic

decorations.

The Nine Dragons Wall at Beihai Park in Beijing, China.

The Nine Dragons Wall at Beihai Park in Beijing, China.

|

|

NOVA: The dragon seems to be a popular motif in Chinese art. What is its

significance?

Wu: Well, the Chinese have regarded themselves as the descendants of the

dragon. That's why I named my 1997 exhibition at the MFA "Tales from the

Land of Dragons." In ancient China, the Emperor's face used to be called the

dragon face. The emperor's throne was referred to as a dragon throne, and his

robe dragon robe. The dragon is also one of the four direction animals,

representing the East. The dragon motif has been around with the Chinese for a

long while. The earliest figurative presentation of a dragon took place in

China's Neolithic period, dating back to the 5th millennium B.C. However, no

one knows what exactly a dragon is. There are many theories—maybe it's a

stylized crocodile, or a dinosaur, or a mixture of several wild animals. Most

importantly, the Chinese dragon symbolizes auspiciousness, just the opposite of

the Biblical dragon in Western cultures.

NOVA: Could you tell us a little about yourself? What turned you on, so to

speak, to the study of Chinese art?

Wu: I have always loved to draw and paint. In my high-school years I learned

surrealist paintings. I especially liked Paul Klee. But during my freshman year

in college, a professor who was a Manchu prince and was renowned for his

Chinese calligraphy, ink painting, and poetry, turned me around 180 degrees. I

then started to devote myself to classical Chinese learning—from literature

to poetry, to calligraphy, to painting, to connoisseurship in ancient

paintings. After I finished my B.A. degree in 1962, I became a part of the

curatorial staff at the National Palace Museum in Taiwan, where 12 centuries of

imperial art collections have been kept since 1949.

Then, by luck, several American scholars came to the Palace Museum with a large

grant to photograph tens of thousands of masterpieces, and I was assigned to

assist with this important project. Since this large body of photographs was to

be housed at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, and Professor Richard

Edwards from U. of M. was very kind to me, I was able to receive scholarships

to pursue a graduate degree there. During my years in Michigan, I also worked

for projects at the Cleveland Museum and the Nelson-Atkins Museum.

NOVA: How did you end up here in Boston?

Wu: In 1970 an opening suddenly appeared at the MFA. Mr. Sickman, then the

director of the Nelson-Atkins Museum in Kansas City, recommended me for the

position. I had already heard about the outstanding art collections at the MFA

and was willing to interrupt my Michigan Ph.D. program in order to take up the

job. I started in Boston as a Research Fellow for Chinese Art in 1971 and was

named Curator of Asiatic Art in 1985. Now I serve as the Head of the Department

of Asia, Oceania and Africa.

|  This Ming dynasty "fish jar" sold for a record-setting

$5.7 million at a Hong Kong auction.

This Ming dynasty "fish jar" sold for a record-setting

$5.7 million at a Hong Kong auction.

|

NOVA: Can you describe what you look for when you bid or purchase a piece for

the museum?

Wu: When I acquire an artwork for the museum, I always consider five key

issues: its quality, its authenticity, its rarity, its historical, cultural and

religious significance, and how it would fit in our permanent collection. If

the answers are thumbs up, then I'll recommend the artwork to the museum

director and deputy director for approval.

NOVA: Do you usually buy pieces at auction?

Wu: Auction is a major source, of course. Donations are another important

source. Individual dealers, too, approach us with photographs or the original

works for us to consider. Sometimes a private collector might be interested in

selling his or her collection to us.

NOVA: Any final thoughts for our NOVA Online readers?

Wu: I am truly grateful for how much I have experienced and learned and

benefited from working in the United States. Your country, of course, is a much

younger country than India and China, which each have several thousand years'

history. On the other hand, you also do not have the heavy burden of history

and tradition and conventions. I think Americans are always looking forward,

whereas people in old countries like China and India are often looking back. That's why

India and China cannot move forward as easily or as fast as the United States.

I think because of working here, my knowledge and my scholarship have grown to

a degree that you cannot even get from leading universities. It's not something

you can learn from classrooms. You have to learn through working with the art,

with people who love art, and with administrators who care for art.

Photos: (1) Rick Groleau; (2, 4-5) Corbis Images; (3) Courtesy of Gedeon Communications.

On China's China |

Ancient Chinese Explorers

Asia's Undersea Archeology |

Date the Dish |

Resources

Transcript |

Site Map |

Sultan's Lost Treasure Home

Editor's Picks |

Previous Sites |

Join Us/E-mail |

TV/Web Schedule

About NOVA |

Teachers |

Site Map |

Shop |

Jobs |

Search |

To print

PBS Online |

NOVA Online |

WGBH

© | Updated January 2001

|

|

|