|

|

|  Zheng He (1371-1433), the great Ming navigator.

Zheng He (1371-1433), the great Ming navigator.

|

Ancient Chinese Explorers

Part 2 | Back to part 1

Exploits of the eunuch admiral

Zheng He commemorated his adventures on a stone pillar discovered in Fujian province

in the 1930s. His mission, according to the pillar, was to flaunt the might of

Chinese power and collect tribute from the "barbarians from beyond the seas."

On his first trip, leading more than 60 massive galleons, Zheng He visited what

would later become Vietnam and reached the port of Calicut, India. On his

return, he battled pirates and established massive warehouses in the Straits of

Malacca for sorting all the goods accumulated on this and subsequent voyages.

While voyaging to India, the ships encountered a ferocious hurricane. Zheng He

prayed to the Taoist Goddess known as the Celestial Spouse. In response, a

"divine light" shone at the tips of the mast, and the storm subsided. This

heavenly sign—perhaps the static electrical phenomenon known as St. Elmo's

fire—led Zheng He to believe that his missions were under special divine

protection.

The emperor launched Zheng He's fourth and most ambitious voyage in January

1414. Its destination was Hormuz on the Persian Gulf, where artisans strung

together exquisite pearls and merchants dealt in precious stones and metals.

While Zheng He lingered in the city to amass treasure for the emperor, another

branch of the fleet sailed to the kingdom of Bengal in present-day Bangladesh.

Here the travelers saw a giraffe that the east African potentate of Malindi had

presented to the Bengal ruler. The Chinese persuaded their hosts to part with

the giraffe as a gift to the emperor and to procure another like it from

Africa. When the giraffe arrived at the court in Nanjing in 1415, the emperor's

philosophers identified it, despite its pair of horns, as the fabled

chi'i-lin or unicorn, an animal associated with an age of exceptional

peace and prosperity. As the fleet's merchants laid treasures from Arabia and

India at the feet of the emperor, this omen must surely have seemed

fitting.

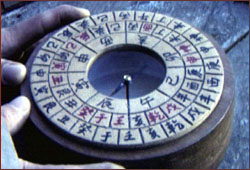

To navigate throughout the Indian Ocean, Zheng

He would have made use of the magnetic compass, invented in China during the

Song dynasty.

To navigate throughout the Indian Ocean, Zheng

He would have made use of the magnetic compass, invented in China during the

Song dynasty.

|

|

The initial diplomatic contact with Malindi now encouraged Zheng He to plan a

direct trading voyage to eastern Africa. Landing at Somalia on the coast, he

found himself offered such exotic items as "dragon saliva, incense, and golden

amber." But even these substances paled before the extraordinary beasts that

were loaded on board his ships. Lions, leopards, "camel-birds" (ostriches),

"celestial horses" (zebras), and a "celestial stag" (oryx), were shipped back

to the imperial court. Here officials showered congratulations on Zheng He and

bowed low in awe before the divine creatures that accompanied him.

End of an era

Toward

the end of his seventh voyage in 1433, the 62-year-old Zheng He died and was

said to have been buried at sea. Although he had extended the wealth and power

of China over a vast realm and is even today revered as a god in remote parts

of Indonesia, the tide was already turning against foreign ventures.

The conservative Confucian faction now had the upper hand. In its worldview, it

was improper to go abroad while one's parents were still alive. 'Barbarian'

nations were seen as offering little of value to add to the prosperity already

present in the Middle Kingdom.

The renovation of the massive Grand Canal in 1411 offered a quicker and safer

route for transporting grain than along the coast, so the demand for oceangoing

vessels plummeted.

In addition, the threat of a new Mongol invasion drew military investment away

from the expensive maintenance of the treasure fleets. By 1503 the navy had

shrunk to one tenth of its size in the early Ming. The final blow came in 1525

with the order to destroy all the larger classes of ships. China was now set on

its centuries-long course of xenophobic isolation.

|  Impressive as they are, Chinese junks today are but pale shadows of medieval

Chinese ships.

Impressive as they are, Chinese junks today are but pale shadows of medieval

Chinese ships.

|

Historians can only speculate on how differently world history might have

turned out had the Ming emperors pursued a vigorous colonial policy. As it is,

porcelain shards washed up on the beaches of east Africa and old men's

folktales of shipwreck are among the few tangible relics of China's epic

voyages of adventure.

Evan Hadingham is NOVA's Senior Science Editor.

Further Reading

When China Ruled the Seas. By Louise Levathes. New York: Oxford University

Press, 1994.

Archaeology and the Social History of Ships. By Richard A. Gould. New

York: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

"The Rise and Fall of 15th Century Seapower." By Michael L. Bosworth. See

www.cronab.demon.co.uk/china.htm.

"1492: The Prequel." By Nicholas D. Kristof. The New York Times, June 6,

1999.

"Chinese Maritime History and Nautical Archaeology: Where Have All the Ships

Gone?" By Hans Van Tilburg. See

www.mm.wa.gov.au/Museum/aima/bulletins/Bulletin18_2/China.html

Photos: (1) Pierre Corrade; (2-4) Courtesy of Instructional Resources Corporation, http://www.historypictures.com.

On China's China |

Ancient Chinese Explorers

Asia's Undersea Archeology |

Date the Dish |

Resources

Transcript |

Site Map |

Sultan's Lost Treasure Home

Editor's Picks |

Previous Sites |

Join Us/E-mail |

TV/Web Schedule

About NOVA |

Teachers |

Site Map |

Shop |

Jobs |

Search |

To print

PBS Online |

NOVA Online |

WGBH

© | Updated January 2001

|

|

|