|

|

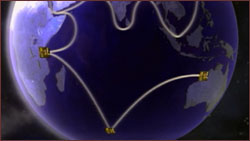

|  Overseas trading of fine porcelain and other

objects began in China during the Song Dynasty.

Overseas trading of fine porcelain and other

objects began in China during the Song Dynasty.

|

Asia's Undersea Archeology

by Richard Gould

Seaborne commerce on a large scale in Asia dates to the Song Dynasty of

China (A.D. 960-1270). The Mongols in the succeeding Yuan Dynasty (ca.

1271-1368) went on to build even more ships on a grand scale, and during his

stay at the imperial court from 1275 to 1292, Marco Polo described four-masted,

seagoing merchant ships with watertight bulkheads and crews of up to 300. Early

in the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), an expansion of seaborne trade took place with

the construction of an immense treasure fleet—reported to consist of 317

ships when it was assembled in Nanjing in 1405—that made trading cruises

throughout the Indian Ocean and the China seas (see Ancient Chinese

Explorers).

Ming seaborne commerce declined rapidly during the mid-15th century as a result

of conflict between the court and the merchants over control of the trade. The

emperor eventually declared the construction of any ship with more than two

masts a capital offense, authorized the destruction of all oceangoing ships and

the arrest of merchants who sailed them, and declared it a crime even to go to

sea in a multimasted ship.

Shipbuilding in the Song, Yuan, and Ming

Although shipwreck archeology is relatively new in Asia, important finds are

pointing the way toward the broader use of archeological evidence relative to

the documentary history of this era of Chinese maritime expansion. One cannot

always assume the documents to be detailed or accurate. As the English maritime

historian G.R.G. Worcester pointed out,

No writer of nautical experience has described these vessels [large ships of

the Mongol Dynasty] or provided us with information on which reliance can be

placed. Writers on shipping were, or seemed to be, practically unknown in those

days; the few that refer to [shipping] are so inaccurate and laconic, or both,

that their works have little real value, and so everything relating to the

ships of the period is in a great degree a matter for conjecture.

Ming merchants sailed as far as Africa to trade goods.

Ming merchants sailed as far as Africa to trade goods.

|

|

No less an authority than the historian of technology Joseph Needham shared

this view. Needham pointed out that "systematic nautical treatises did not

arise in Chinese culture, or at least did not get into print." Furthermore,

European observers in medieval-era Chinese ships, including Marco Polo, were

characteristically impressed by their seaworthiness but at the same time

described them in Eurocentric terms on the basis of what they lacked—such as

keels, sternposts and stemposts, centerline rudders attached to the sternpost,

and masts that were not positioned along the ship's longitudinal centerline.

Often the interpretation based upon such observations was that Chinese

ship-building evolved in isolation from the rest of the world, especially from

the West. "As in so many other areas of activity," wrote maritime archeologist

Keith Muckelroy, "the craftsmen of China developed their own designs and

techniques, owing little if anything to outside influences and having

surprisingly little impact on ideas in neighboring lands."

It remains to be seen how isolated Chinese shipbuilding was during its zenith

in the Song, Mongol (Yuan), and Ming Dynasties, but it seems appropriate here

to remind archeologists to be wary of the fallacy of affirming the consequent.

That is, archeologists have a tendency to assume the very thing they should be

trying to find out. Most often this takes the form of the discovery of

something in the past to prove information derived from historic texts or

present-day observations.

Instead of assuming cultural isolation on the part of historic Chinese

shipbuilders and sailors, perhaps we should be using archeological evidence to

find out whether this was the case. The Australian maritime archeologist Jeremy

Green points out that following the imperial ban on overseas voyaging during

the Ming Dynasty, shipping increased along China's inland waterways and coasts.

This suggests that 19th- and early 20th-century

historical accounts of later Chinese ships were biased toward shallow-water

craft intended for use on canals, rivers, and close to shore—quite a

different maritime tradition from this earlier period in Chinese

history.

|  Gould argues that scholars should use

archeological evidence to prove or disprove the validity of historical

accounts, not vice versa.

Gould argues that scholars should use

archeological evidence to prove or disprove the validity of historical

accounts, not vice versa.

|

The Quanzhou wreck

The best archeological evidence available so far for this period comes from the

wreck found during canal dredging in 1973 of a large ship buried in muck at

Houzhou. Houzhou lies about six miles from Quanzhou, an important Song trading

port in what is now Fujian Province. In a series of reports, People's Republic

of China archeologists excavated and reported on the hull remains of the

Quanzhou ship, which are now on display at the Overseas Communications Museum

at Quanzhou.

The ship was about 114 feet long by 32 feet wide, with a displacement of

roughly 375 tons. The archeologists found more than 500 copper coins associated

with the wreck, 70 of which were minted during the Southern Song period (ca.

1127-1279), with the latest ones dating to 1272. The ship probably sank soon

after that date.

Associated with the ship remains were about 5,000 pounds of fragrant wood,

probably from either mainland or island Southeast Asia, and assorted materials

such as cowrie shells, ambergris, cinnabar, betel nut, pepper, and

tortoiseshell, all attributed to sources in Somalia—in other words, a

priority cargo. (Priority cargoes were processed and/or packaged in

archeologically identifiable ways that set them apart from unprocessed or

unpackaged bulk cargoes.) Although historical accounts of Chinese seaborne

commerce described organized trading expeditions, these archeological

associations could just as easily have resulted from tramping—that is, ships

not making point-to-point voyages but taking on and trading cargo at various

ports along the way—or even sustained cross-cultural trading partnerships.

The archeological team also found remains of supplies relating to the ship's

provisioning and operations, including faunal remains of possible food animals

(bird, fish, goat, pig, and cow) and dogs and rats (eaten, too?) as well as

plant remains of food items (coconuts, olives, lychees, peaches, and plums).

Portable artifacts included an axe, a wooden ruler, and a bronze ladle—all

useful items for maintaining the ship during its voyages—and assorted

celadon bowls, a stoneware wine jar, Chinese chessmen, glass beads, and other

personal items and tableware.

Like the

Brunei wreck, on which this diver has uncovered a porcelain artifact, the

Quanzhou wreck held an enormous cargo of goods.

Like the

Brunei wreck, on which this diver has uncovered a porcelain artifact, the

Quanzhou wreck held an enormous cargo of goods.

|

|

Remains of the Quanzhou ship's hull were preserved up to the waterline,

permitting detailed study of important elements of the ship's construction. The

presence of transverse bulkheads agrees with early historical accounts such as

Marco Polo's, but in other respects, such as the claim for alternately stepped

masts and the absence of a keel, the archeological findings differ from

literary and ethnographic sources. The archeology of the Quanzhou ship presents

evidence of an oceangoing commercial vessel comparable in size to the largest

known European merchant ships of its time, which was engaged in trade of

priority goods around the Indian Ocean from East Africa to the southeast coast

of China. The archeological associations of both the ship's structure and its

contents are ambiguous about the conduct of the trade, beyond the general

implications of long-distance commerce and about whether the ship followed a

coastline route or engaged in true oceanic voyaging.

Continue: Evidence from South Korea

On China's China |

Ancient Chinese Explorers

Asia's Undersea Archeology |

Date the Dish |

Resources

Transcript |

Site Map |

Sultan's Lost Treasure Home

Editor's Picks |

Previous Sites |

Join Us/E-mail |

TV/Web Schedule

About NOVA |

Teachers |

Site Map |

Shop |

Jobs |

Search |

To print

PBS Online |

NOVA Online |

WGBH

© | Updated January 2001

|

|

|