|

|

|

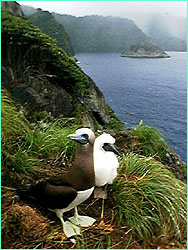

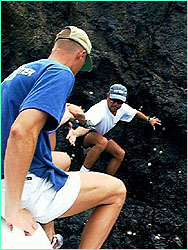

by Peter Tyson October 15, 1998 We should have known it was going to be a rough day when Howard Hall slipped. The panga had eased to within spitting distance of the jagged northern tip of Manuelita, the small island off the north coast of Cocos. Foamy chop threatened to heave the boat into the cliff, but with deft movements Pepe Monge skilfully held it just close enough for our fearless leader to make the pioneering leap onto the islet. Alas, the rocks were sheathed in booby guano and seaspray, and he lost his grip. He plunged up to his chest in the rocky surf, leaving a nasty gash on his right calf. Undeterred, Hall quickly regained the cliff and began the process of ferrying gear from the panga to the island along a rope held by people on both sides. IMAX camera, film rolls, tripod, and other gear, all safely sealed in dry bags, dangled momentarily over the waves before settling safely on solid rock. We were heading up to film booby birds for the IMAX film, and perhaps a sunset as well. No matter that it was pouring rain; weather at Cocos can change at the drop of a filmmaker. At the moment, though, Manuelita did look imposing. William Beebe ("bee- bee"), an ichthyologist and explorer who visited Cocos in 1925, said every time he looked at Manuelita it reminded him of Arnold Böcklin's Island of the Dead. I know that painting, and Beebe is right. Manuelita, particularly in gloomy weather or in the brief tropical twilight, looks like some great sea monster rearing out of Chatham Bay. A quarter mile long by less than a 100 feet wide at its thickest, its colossal curved back of gray columnar basalt arches 150 feet into the sky. Tufts of grass cling impossibly to its sheer flanks like some kind of strange fur, while green-leaved fig trees with long, dangling roots make it appear as if the monster has just burst forth from a bed of seaweed. "There's one thing I won't miss when I leave Cocos," Billy Holdson told me. "Booby stench." As we started up the island's rugged spine, I had to laugh. The pungent fragrance of booby poop hit us with the force of a squall. Whenever I reached up for a solid grip, my hand came away with a smear of greenish goo. Every rock, every leaf, every blade of grass was greased with the stuff. We moved as if on ice, using fixed ropes that Hall's crew had left in place from previous excursions there. It was too hot to wear raingear, and our t-shirts were soon soaked through. To add insult, brown boobies nesting everywhere on the ground thrust their rapier beaks at our bare ankles when we passed too close. Mark Conlin received a slice or two not unlike the one Hall had gotten earlier.

These bigger chicks had the routine down. Whilst left alone, they stood defiantly on the twiggy nest, feet splayed wide, pecking just as their parents do at those who approached too close. But when mom or dad returned with lunch, they made as if their wings had been broken and flopped about in the nest, looking helpless. Squawking obstreperously, they poked so determinedly at their parent's beak that I was amazed they didn't put an eye out. Maybe it took the adults awhile to bring up the half-digested fish, or maybe they were just trying to teach their offspring a little patience. But eventually, with the youngster's beak thrust deep into its parent's crop, up it came. "Ugh!" "Yuck!" "Regurgitated fish again, Mom? Can't I have something else for a change?" Watching greenish slop spill off a chick's beak inevitably sent the film crew into paroxysms of imitation gagging and vomiting. They stuck their fingers down their throats or turned away and made ghoulish faces. The same occurred whenever a booby let fly with an explosive burst of freshly minted guano. On a previous visit up there, Holdson had fallen victim to one such four-foot blast. Hall, seeing it coming, told me later that "I thought of holding something in the way, but then thought, 'Nah.'" It hit Holdson right in the back of the head. More paroxysms. Anything to relieve the monotony of waiting for hours in the pouring rain. For hours it was. The rain would let up, then pick up, let up, pick up, over and over. Conlin pointed to a patch of sun far out to sea: "Look, it's coming our way." Yeah, right. It just sat there, three or four miles distant, tantalizingly out of reach. Cocos itself lay largely hidden beneath a blanket of saturated clouds. After his visit in 1925, Beebe wrote that the island is "very often veiled by such heavy mists and rainstorms that a ship may pass within a few miles without glimpsing a trace of [Cocos], the very existence of [which] has been denied in comparatively recent times." Beebe had an experience with boobies—one that the Halls have also had—that shows just how far off the beaten track Cocos lies. A fierce storm came up one night, and booby birds, dazed by the electric lights of Beebe's ship, began alighting on the deck by the hundreds. "Nothing showed the complete absence of man from this island as much as this," Beebe wrote. "The terrific wind and blinding rain utterly confused the birds. All doors had to be closed, for otherwise they filled the staterooms and laboratory, and their long, thrashing wings worked havoc until we ousted them." Ever the curious scientist, Beebe at one point tied a handkerchief to the leg of a booby and cast the bird to the winds. "[A] minute later it was again at my feet, and I retrieved my property."

One second Hall was sitting as he had been for three hours, staring through sheets of rain at the ocean. The next, without so much as a word, he was donning his backpack. The weather had won. As we made our way back along the slippery rocks and fixed ropes, Conlin said he was astonished Hall had given up. Normally he'd wait till the bitter end, long after everyone else was ready to throw in the towel. And more than once he'd been rewarded, with a late-breaking sun on Manuelita, or an enormous school of hammerheads. Such devotion to the cause is what makes Hall such a successful filmmaker. ("Patience and perseverance," Conlin told me later. "The two things that Howard has taught me most of all.") Looking at the horizon as we descended, I knew Hall had made the right decision. It was socked in. No sudden clearing was in the offing, such as that Beebe saw one day when "one cloud lifted with amazing rapidity and revealed Cocos Island, clear and green, as the handkerchief of a conjurer is raised and displays a bouquet of exquisite flowers where a moment before there had been nothing." At least Hall wasn't leaving anything to chance. And that included renegotiating those slick rocks that had done him mischief on the way in. As the rest of us clambered one at a time back aboard the bouncing panga, Howard and Michele stripped down to their suits and leapt into the ocean. Peter Tyson is Online Producer of NOVA. Hammerheads or Bust (Sept. 23) Get Used To It (Sept. 25) Nature Reigns at Cocos (Sept. 27) The PIG and the Process (Sept. 29) Hammerheads Sighted (Oct. 1) Assault on Cocos (Oct. 3) The Director's Cut (Oct. 5) Swimming with Whitetip Reef Sharks (Oct. 7) The Magnificent Seven (Oct. 9) The Search for Lake Cocos (Oct. 11) Courtship of the Marbled Rays (Oct. 13) Of Booby and Beebe (Oct. 15) Taken by Surprise (Oct. 17) "This is Cocos, This is Cool" (Oct. 19) Cocos Island | Sharkmasters | World of Sharks | Dispatches E-mail | Resources | Site Map | Sharks Home Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule | About NOVA Watch NOVAs online | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Search | To Print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated June 2002 |

Brown booby and nestling, with a rainy Cocos in the background.

Brown booby and nestling, with a rainy Cocos in the background.

Billy Holdson (in shades) and Peter Kragh lend a hand getting the film crew

onto Manuelita.

Billy Holdson (in shades) and Peter Kragh lend a hand getting the film crew

onto Manuelita.

A lone booby chick courageously stands its ground.

A lone booby chick courageously stands its ground.