|

|

|

The Search for Lake Cocos by Peter Tyson October 11, 1998 "[T]hat which contributes most to the Pleasure of the Place is, that a great many Springs of clear and sweet Water rising to the top of the Hill, are there gathered as in a deep large Bason or Pond...."

We reassembled our old team from the Yglesias climb: the biologists Claudine Sierra, Roberto Plaza, and Alvaro Farias, and myself. Avi Klapfer, owner of the Undersea Hunter, also joined us. Our goal was to hike from Wafer Bay on the north coast to Yglesias Bay on the south. (We had planned to hunt pigs for Sierra's research, but the park ranger who would do the hunting chose not to come.) On the way, we would pass through the Plains, where signs of an ancient lake might lie. We would also pass through parts of the island that few, if any, had ever seen. A map from the 1920s that I use as reference declared the part of the south coast to which we were headed "uncharted," an alluring word if ever there was one. Even Sierra, who has covered more of the island on foot than perhaps anyone else alive, had not visited the area. After a large breakfast aboard the Undersea Hunter, Klapfer and I motored over to Wafer Bay to join the others. As ever, the myriad waterfalls spilling out of the heights made for an impressive sight. Wafer, furthering his argument for a lake, wrote that the top of "the Hill" subsided inwards "quite round; and the Water, having by this means no Channel whereby to flow along, as in a Brook or River, it overflows the Verge of its Bason in several Places, and runs trickling down in many pretty Streams." I could see how someone standing on the deck of a ship below might think that all those waterfalls, many of which appear to fall from the same height, might be draining a lake out of sight over the brim.

That despite the rocky substrate. The Plains was so rocky that the roots of giant fig trees had nowhere to go but out to the sides like fire hoses flung on the ground. And the Plains were flat as a plate for a good mile. Could this be the bed of an erstwhile lake? I asked Sierra, even though I knew her answer; I could see it for myself. "How could it be?" she said, surprised at my question. "Los Llanos drops off on all sides." Indeed, the Plains were more a Plateau, raised like an island amidst the surrounding Wafer Bay watershed. A large puddle might have existed here, but no lake. When we left the Plains behind, we entered the "uncharted" territory of my 1920s map. There were no trails, no landmarks that Sierra could use to find her way through more of what my map labeled as "dense tropical forest and a thick undergrowth of tall grass, vines, shrubs, and bramble bushes." I asked her how we'd find Yglesias Bay, which lay on the other side of a 1,300-foot mountain. "Common sense," she said, and then added, "which we don't have a lot of." But I knew she did, and over the next few hours I watched her work skillfully with the two tools we had to ensure our release from the confines of the forest: a compass and a laminated topo map of Cocos. With our legs smeared with mud and our shirts soaked with half rain, half sweat, we climbed up and down one steep, slippery slope after another, grasping thin tree trunks for balance and trying to avoid a species of grass that left wounds like paper cuts on any exposed flesh. Whenever we gained a ridge, it was tempting to follow its quasi-level surface. But then Sierra's arm would shoot up, pointing out our heading, which inevitably led down or up rather than along. Every now and then, sensing something close behind me, I'd turn to see a fairy tern flapping silently a few feet away, its marble-like black eyes throwing out a challenge to me. The Costa Ricans call this dove- like white bird "Espiritu Santo," the Holy Ghost bird.

Gaining the summit of the long-awaited 1,300-foot peak, we dropped to the ground amidst a garden of moss-draped tree ferns and ate a lunch of ham sandwiches, chocolate, and water. Afterwards, we climbed into the loftiest trees we could find for a glimpse of Yglesias Bay far below. It looked so close, and yet was so far. Felipe Aviles Briceno, the park ranger, had warned us not to try to reach the bay via the famous waterfall; we'd find ourselves at a vertical drop of several hundred feet. So, rested from our short break, we headed straight downhill towards the coast. That's when things got hairy. The mountainside was so steep that every step became an act of extreme delicacy and precision. Once I lost my footing and slid 30 near-vertical feet down the remains of a landslide before somehow stopping myself. Another time, to get below a bluff, I had to shimmy down a tree trunk like a fireman down the pole. I chose a diagonal path down the hill, because rocks dislodged by those above me kept zipping past my head at high speed. By the time we reached the river below the waterfall, our legs and arms were a tracework of bloody scratches. But the falls made it all worth it. The lower of the two stages, it poured over a lip of lava and free-fell 200 feet into a deep pool. It reminded me of Bridal Veil Falls in Yosemite, with its self-generated wind whipping curtains of water off to either side, staining the surrounding escarpment black. This same "wind" blasted water out from the base of the falls, making it impossible to look in that direction while swimming in the pool, as we did. I was afraid those hurricane-force gusts might snatch the contact lenses right off my eyeballs. Belcher was probably describing this very waterfall when he wrote that "the magnificent S.W. cliffs and waterfalls, like silver threads, leaping from the richest and varied tints of green that can be imagined, would put a painter in ecstasy." While shoring up his claim for a lake, Wafer, too, might have been thinking of this cascade when he wrote that "in some places of its overflowing, the rocky Sides of the Hill being more than perpendicular, and hanging over the Plain beneath, the water pours down in a Cataract, as out of a Bucket, so as to leave a Space dry under the Spout, and form a kind of Arch of Water...."

Wafer and Belcher were mistaken, in my humble opinion. There was never a lake on Cocos. Belcher's men were either delusional or lying, and neither Belcher nor Wafer saw a lake. It was simply the only way to explain so much water flowing off such a small island. I might have reached the same conclusion had I not traversed a good portion of the island since I arrived here two weeks ago. But Wafer was right about one thing when he wrote that "together with the advantage of the Prospect, the near adjoining Coco-nut Trees, and the freshness which the falling Water gives the Air in this hot Climate, [the waterfalls make] it a very charming Place, and delightful to several of the Senses at once." Peter Tyson is Online Producer of NOVA. Hammerheads or Bust (Sept. 23) Get Used To It (Sept. 25) Nature Reigns at Cocos (Sept. 27) The PIG and the Process (Sept. 29) Hammerheads Sighted (Oct. 1) Assault on Cocos (Oct. 3) The Director's Cut (Oct. 5) Swimming with Whitetip Reef Sharks (Oct. 7) The Magnificent Seven (Oct. 9) The Search for Lake Cocos (Oct. 11) Courtship of the Marbled Rays (Oct. 13) Of Booby and Beebe (Oct. 15) Taken by Surprise (Oct. 17) "This is Cocos, This is Cool" (Oct. 19) Cocos Island | Sharkmasters | World of Sharks | Dispatches E-mail | Resources | Site Map | Sharks Home Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule | About NOVA Watch NOVAs online | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Search | To Print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated June 2002 |

Mt. Yglesias from afar.

Mt. Yglesias from afar.

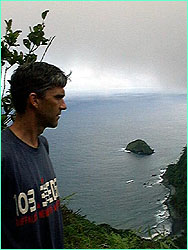

Peter Tyson high over Yglesias Bay.

Peter Tyson high over Yglesias Bay.

The lower stage of the waterfall above Yglesias Bay.

The lower stage of the waterfall above Yglesias Bay.

Soaking from a day in the rain, we enjoy a fire while awaiting our ride home.

Soaking from a day in the rain, we enjoy a fire while awaiting our ride home.