|

|

|

by Peter Tyson October 7, 1998 "Listen to them whine about a simple night dive," said Bob Cranston of his fellow divers, who were kvetching last night about having to dive after such a nice dinner of barbecued pork chops and vanilla ice cream with chocolate sauce. Howard Hall wanted to shoot yellow cup corals off Manuelita. "Howard," Cranston continued, "I think you should fire them all at the end of this trip." "I plan to," Hall said, not missing a beat. "Adios, you blood-sucking leeches." It was easy for them to joke. If you include the Undersea Hunter's owner and divemaster, both of whom have been assisting the film crew, they have 191 years of scuba diving experience among them. Some of them were doing night dives while I was sleeping off another day at elementary school in the late 1960's. I, by contrast, had made precisely one night dive. It took place in Boston Harbor a month ago, in 20 feet of murky water that we walked into off a beach. It was so tame it might as well have been in a swimming pool. As we pulled on our wet suits, I thought with a twinge of despair, I'll probably win the Scuba Tuba Award tonight. The award is named for a balloon- like safety device we all carry with us; if you get swept out to sea while diving, you add air from your tank to the Scuba Tuba, which blows up to six feet tall so someone can see you and come get you. You don't get the Scuba Tuba for doing something stupid, Hall informed me, but for getting caught doing something stupid. Cranston is the current trophy holder, having come up just too far off the Halls' dive boat in a ripping current while filming in British Columbia that he had to be picked up. Being plucked out of the water by a skiff is de rigueur for your average sport diver, but for professional divers like these, who pride themselves on 191 years of experience, it's akin to being caught with your pants down. So fearful are the members of Hall's crew of earning this dubious distinction, Hall says, that on more than one occasion he's found himself relaxing on the dive platform sipping a beer while one of his returning divers swims against a vicious current a few feet from the stern, finning for all he's worth and puffing through his snorkel as if hyperventilating. "All he has to do is hold up his hand, and I'll throw him a rope," Hall laughs. Not a chance. The story reminded me of that Roy Lichtenstein cartoon in which a young woman treading water with her ship sinking the distance cries out, "I'd rather drown than call Brad for help!"

Not going? Who was I to buddy with? "Just go on down, you don't need a buddy." What? No buddy? Then I remembered Michele Hall's comment that, for these guys, you're buddy-diving when you're in the same ocean. It was just another cardinal rule of sport diving being broken with impunity. Always dive with a buddy. Another is: Never hold your breath. Why? Because as you ascend, the air in your lungs expands; if you hold it in, you can do serious damage. But I wasn't with sport divers, was I? No; it turns out these guys hold their breath all the time. They don't teach you this in beginner diving, but you can hold your breath just fine if you remain at any one depth, even if it's 100 feet. In fact, Kragh told me he'll regularly hold his breath and ascend from, say, 100 to 70 feet while chasing hammerheads that he doesn't want to scare away with his bubbles. (Don't try that at home.) As we gathered up our gear, Mark Conlin told me, to a general guffaw from his Übermensch pals, "We're the last people to stick to those rules you learned in your scuba certification class." That was reassuring. I thought again of those four divers who were carried out to sea last year while diving the very site we were about to dive—Manuelita—only to be found five hours later five miles out to sea. They were fine, but that was during the day. (Fortunately, Hall didn't tell me till this morning the story of six Japanese divers swept out to sea in Palau while he was doing a shoot there not long ago; they weren't found for four or five days, and all had died from exposure.) An arm of the Humboldt Current swings right past Cocos, sideswiping Manuelita, to end up ultimately in Hawaii. Would I be on my way to Honolulu within the hour, blowing up a Scuba Tuba that nobody could see in the dark anyway? As I made my way to the panga past wet suits dangling from hangers like the bodies of hanged men, I felt like I was being sucked into a black hole, and no one could even be bothered to notice. We motored only 50 feet away from the Undersea Hunter before stopping. The film crew quickly dispersed beneath the black waves. I sat on the edge of the boat, checking my gear.With Reiner the panga driver beaming in the harsh light of a bare bulb swinging from the boat's canopy, I turned on my dive light, held my mask, and flipped backwards into the night. At first the water looked as murky as it had in Boston Harbor, only it was green rather than brown (and there were no old tires or rusted beer cans). Soon, however, I could see the powerful movie-camera lights of the film crew through the gloom. Half-wondering if I'd get snatched away by an errant current, I made a beeline for those lights. A minute later, I was on the bottom, 50 feet down, with the surrounding coral reef lit up by Halls' lights like a night game at the ballpark.

There were other creatures as well, of course. As with a big city, a whole new set of dwellers comes out at night. The sea urchins were out in force; you had to be mindful where you put your hand. Bright red squirrelfish swam about unconcerned, while other fish hid in coral crannies too small for the sharks to penetrate with their broad snouts. I watched two or three moray eels, including a brown-and-white-striped zebra moray, slink between coralline boulders like snakes. Every now and then I swam closer to Hall to watch him and his team park the giant IMAX camera on a tripod in front of a tiny yellow cup coral. At night, these delicate animals blossom like flowers to feed on plankton in the passing current. But it was the ever-circling whitetips that held me spellbound. It was as if we had dropped down into a nest of piscine vipers. ("The place was swarming with them," Mark Thurlow said later.) Some of the sharks were shorter than my forearm, others outsized me. Hovering on the edge of the light spilling forth from Hall's lamps, I periodically shut off my own light—and held my breath, by God—in order to encourage these sleek, awe-inspiring animals to accept me to a slightly greater degree into their alien world, to feel slightly less a stranger in a strange land. Billy Holdson, who'd agreed to be my buddy at the last moment, came over at one point and signaled that he was heading up—did I want to come? Not a chance. I hung out down there for nigh on an hour, till my air ran low. All I could think was, I can hardly wait to do this again. I mean, why whine about a simple night dive? Peter Tyson is Online Producer of NOVA. Photos: (1) ©Michele Hall/Howard Hall Productions; (2,3) Peter Tyson; (4) ©Howard Hall/Howard Hall Productions. Hammerheads or Bust (Sept. 23) Get Used To It (Sept. 25) Nature Reigns at Cocos (Sept. 27) The PIG and the Process (Sept. 29) Hammerheads Sighted (Oct. 1) Assault on Cocos (Oct. 3) The Director's Cut (Oct. 5) Swimming with Whitetip Reef Sharks (Oct. 7) The Magnificent Seven (Oct. 9) The Search for Lake Cocos (Oct. 11) Courtship of the Marbled Rays (Oct. 13) Of Booby and Beebe (Oct. 15) Taken by Surprise (Oct. 17) "This is Cocos, This is Cool" (Oct. 19) Cocos Island | Sharkmasters | World of Sharks | Dispatches E-mail | Resources | Site Map | Sharks Home Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule | About NOVA Watch NOVAs online | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Search | To Print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated June 2002 |

Whitetip Reef Shark

Whitetip Reef Shark

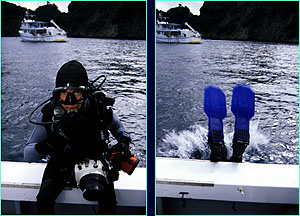

Diver Mark Conlin . . . takes the plunge.

Diver Mark Conlin . . . takes the plunge.

A moray at Manuelita.

A moray at Manuelita.