|

|

|

by Peter Tyson March 19, 1999 Herodotus, the father of history, said famously that Egypt was the "Gift of the River." The same could be said of obelisks, that they are a gift of the Nile, for without the river, the task of shuttling these massive pillars of stone hundreds of miles from quarry to temple would have been orders of magnitude more challenging. Today, our team set out to investigate such river transport of obelisks using a one-tenth scale model of the obelisk barge pictured in relief at Hatshepsut's mortuary temple (see The Queen Who Would Be King). While the First Cataract at Aswan has always hindered boat traffic south of here, the Nile north of Aswan is a conveyor belt that runs unobstructed some 750 miles to the Mediterranean. As a measure of how vital the north-flowing river was to the Egyptians, the hieroglyph for traveling north is a boat with no mast, while that for heading south is a boat under sail. Fortunately for the obelisk raisers, the granite quarries lay upstream of the major capitals, so those in charge of shipping obelisks could harness the Nile to do most of the work of conveying. As we've seen, scholars have one significant clue as to how the Egyptians transported obelisks on the Nile. The obelisk barge pictured in Hatshepsut's relief has two obelisks on it, laid end to end, and is thought to have been over 200 feet long. Other evidence for such prodigious size exists. Aneni, an high official under Tuthmosis I who saw to the erection of his two obelisks at Karnak, claimed in his tomb that he "built the 'august' boat of 120 cubits (207 feet) in length and 40 cubits (69 feet) in breadth for transporting these obelisks." Indeed, one scholar has estimated that such barges might have reached over 310 feet in length, exhibited a beam of 105 feet, and displaced 7,300 tons. For sheer size, obelisk barges were the Pyramids of ancient boats. Some scholars have suggested that the two obelisks in the relief actually traveled side by side on one barge, but in order to show both, the artist had to depict them end to end. Owain Roberts believes the relief merely indicates that two obelisks were moved by boat, and he designed his model to carry one. Mark Lehner, for his part, likes to think that "what you see in Hatshepsut's relief is what they used." While the relief is open to wide interpretation—it is only, says Reginald Engelbach, "an impressionist view"—scholars generally agree that it portrays a boat with three separate sets of crossbeams for added strength, as revealed by three levels of what might be deck beam ends poking through the hull. The barge also had several hogging trusses, rope-and-wood structures arching over the deck that prevented the bow and stern from collapsing under the monoliths' enormous weight. Roberts designed his model with these aspects in mind.

The plan called for testing one proposed method for how the Egyptians loaded obelisks aboard barges: pulling it lengthwise up a ramp and onto the deck. Experts have suggested other ways the Egyptians might have done it (which, like so much else about their engineering achievements, remains a mystery). One of the most prevalent theories is that they dug a channel inland from the Nile and floated the barge directly beneath a spot where the obelisk waited on its sledge. As the Nile rose during its annual flooding, the barge would rise, too, eventually shouldering the sledge and obelisk, which then could be shipped downstream. (In his Natural History, Pliny describes how King Ptolemy Philadelphus transported an obelisk to Alexandria using this method.) Roberts and his son Iolo rigged an elaborate system of ropes, with which a group of pullers standing on either side of the ramp could haul the obelisk sledge up the slope and onto the barge. Hopes were high as Roberts spaced about 20 hired students along ropes stretched out on each side of the ramp. With the NOVA film crew at the ready, a wiry, mustachioed man named Moustafa began yelling out the cadence: "Hela hop! ... Hela hop! ... Hela hop!" Some scholars believe this chant, which doesn't mean anything in Arabic, may actually be a surviving pharaonic work chant. Each of Moustafa's cries rose in a crescendo, with the emphasis falling on "hop!," which served as the mens' cue to lean back on the rope with all their might. Moments before the tugging began, Moustafa had greased the track's surface with moistened tufla, a clay that becomes very slippery when wet, just as his forebears might have done. And it paid off: With each "Hela hop!," the sledge glided forward a few feet. When it settled on the barge deck, a great cheer went up among the Egyptians. It was Pulling Together all over again, albeit on a smaller scale.

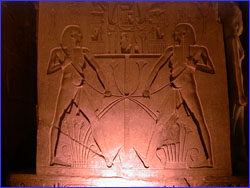

In Hatshepsut's day as in ours, the key element in successfully manipulating obelisks was rope. Lehner today kept stressing the "the power of rope," and the father-and-son Roberts team demonstrated the truth of his statement over and over. They repeatedly relied on "swigging," a means for tightening rope that the ancient Egyptians clearly knew and that we might also use to help raise the big obelisk. They expertly lashed the obelisk to the sledge and rigged the ropes for the ramp pull and for the hogging truss, which they assembled prior to the tow. And they gave a demonstration of the role rope played in holding together the 4,600-year-old Khufu boat (see The Solar Barque). In the midst of the action this afternoon, Lehner reminded me of the so-called "unity of Egypt" emblem. New Kingdom pharaohs liked to inscribe the emblem on their monuments; I've seen at least two on this trip, one on the seated statue of Ramses the Great before Luxor Temple, and another on the Colossi of Memnon. In the emblem, the droopy-breasted Nile god Hapi stands on either side of a post, pulling tight the long stems of a papyrus reed and a lotus plant, which signify northern and southern Egypt, respectively. Striking in its simplicity, the emblem symbolizes the country's unification under the pharaohs. It strikes me that obelisks, brought from Aswan in Upper Egypt not only to Thebes but as far as Heliopolis and other archaic capitals in Lower Egypt, might have symbolized that unity for the pharaohs as well. A unity that is yet another "Gift of the River."

Peter Tyson is Online Producer of NOVA. Obelisk Raised! (September 12) In the Groove (September 1) The Third Attempt (August 27) Angle of Repose (March 25) A Tale of Two Obelisks (March 24) Rising Toward the Sun (March 23) Into Position (March 22) On an Anthill in Aswan (March 21) Ready to Go (March 20) Gifts of the River (March 19) By Camel to a Lost Obelisk (March 18) The Unfinished Obelisk (March 16) Pulling Together (March 14) Balloon Flight Over Ancient Thebes (March 12) The Queen Who Would Be King (March 10) Rock of Ages (March 8) The Solar Barque (March 6) Coughing Up an Obelisk (March 4) Explore Ancient Egypt | Raising the Obelisk | Meet the Team Dispatches | Pyramids | E-Mail | Resources Classroom Resources | Site Map | Mysteries of the Nile Home Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule About NOVA | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Jobs | Search | To print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated November 2000 |

Our two-ton obelisk goes for a ride.

Our two-ton obelisk goes for a ride. "The power of rope" could easily have been our motto

today.

"The power of rope" could easily have been our motto

today.

The "unity of Egypt" emblem on the seated statue of

Ramses II at Luxor Temple, shot after dark.

The "unity of Egypt" emblem on the seated statue of

Ramses II at Luxor Temple, shot after dark.

The NOVA obelisk at its new resting place atop the

ramp.

The NOVA obelisk at its new resting place atop the

ramp.