|

|

|

by Peter Tyson March 8, 1999 As I write this, the recorded voices of muezzin urging the faithful to prayer waft in the open, fourth-floor window of my hotel in Luxor. We arrived here this afternoon from Cairo, prepared to investigate some of the finest monuments of the New Kingdom, including three standing obelisks, before heading south to Aswan. The air is sultry and languid, and the only sound to compete with the muezzin is the collective chirp of a flock of birds in garden trees below. The tranquil scene could not be further from that of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo yesterday. The museum made my head spin. And not because of the crowds. We spent most of the day within the museum's musty, high-ceilinged rooms, and I barely noticed my fellow oglers, even though at times I was half-conscious of bobbing amidst a roiling sea of humanity. No, it's the sheer quantity of stunning artifacts—the mummies of Ramses the Great and other pharaohs, the amazingly lifelike wooden statue known as the "Headman of the Village," and, of course, the luxurious golden treasures of King Tut.

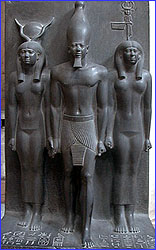

Carved from a single piece of schist, the sculpture epitomizes the Egyptians' skill in working with stone. Even if you've never visited, you know that Egypt's early inhabitants had a remarkable way with rock. Our team spent the weekend on the Giza Plateau, where some of the two-and-a-half-million blocks of the Great Pyramid alone fit so snugly together that, as the 12th-century Arab historian Abd el-Latif noted, neither a hair nor a needle could be edged between them. In the Valley Temple of Khafre, builder of the second-largest pyramid, similarly tight blocks "turn" corners (see photo). And then there's the Sphinx—the Greek word may derive from the Egyptian Shesepankh or "living statue"—one of the most famous stone sculptures ever produced.

Once inside the vast, classical-style museum, Mark Lehner led us into a broad atrium, where my eye was immediately drawn to the enormous seated statues of the pharaoh Amenophis III and his wife perched at one end. But Lehner stopped at the lidless granite sarcophagus of a lesser-known pharaoh of the 21st Dynasty. (The top lay a few feet away.) Leaning over the coffin, he pointed to a rectangular, cigarette-box-sized hole cut into the upper edge of one end. Matched by similar holes on the other three sides, it once held the sarcophagus lid in place. I could see cylindrical marks etched into its sides, ending in dime-sized circles. We were looking at ancient drill holes (see photo). Iron tools did not come into wide use until the 26th Dynasty, about three centuries after this coffin was carved. To the assembled team, Lehner explained how Egyptologists believe the ancients used copper or bronze drills enhanced by sand, whose quartz crystals performed the actual cutting. They're only guessing—no one really knows. (Denys Stocks, an ancient tools specialist, will join the team in Aswan to demonstrate his notion of using copper tools to cut granite.)

"What confidence they had to risk cutting the lid off the base like this," Lehner laughed, running his finger down the striated slice. The sawyer had abandoned his task after the lid broke in half, leaving half a lid half- attached to the bottom of the sarcophagus. (Scholars live to find such cast-offs, which can tell far more about archaic techniques than finished pieces can.) Confidence: Throughout the museum, it showed both in the superior craftsmanship of pieces and in the faces like that of Menkaure gazing out from his schist statue. As we drove back to the Pyramids through Cairo's traffic-clogged streets, thoughts of Menkaure's bold gaze were fixed in my mind. Tomorrow we head to the Valley of the Kings, where the tomb of Ramses VI and Merenptah lie. Peter Tyson is Online Producer of NOVA. Obelisk Raised! (September 12) In the Groove (September 1) The Third Attempt (August 27) Angle of Repose (March 25) A Tale of Two Obelisks (March 24) Rising Toward the Sun (March 23) Into Position (March 22) On an Anthill in Aswan (March 21) Ready to Go (March 20) Gifts of the River (March 19) By Camel to a Lost Obelisk (March 18) The Unfinished Obelisk (March 16) Pulling Together (March 14) Balloon Flight Over Ancient Thebes (March 12) The Queen Who Would Be King (March 10) Rock of Ages (March 8) The Solar Barque (March 6) Coughing Up an Obelisk (March 4) Explore Ancient Egypt | Raising the Obelisk | Meet the Team Dispatches | Pyramids | E-Mail | Resources Classroom Resources | Site Map | Mysteries of the Nile Home Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule About NOVA | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Jobs | Search | To print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated November 2000 |

The funerary mask of King Tut.

The funerary mask of King Tut.

Menkaure's schist statue.

Menkaure's schist statue.

Curved lintel joint in Khafre's Valley Temple.

Curved lintel joint in Khafre's Valley Temple.

Drill holes in granite sarcophagus.

Drill holes in granite sarcophagus.