|

|

|

by Peter Tyson March 18, 1999 Once a pharaoh's builders had quarried an obelisk, the next step—an atrociously labor-intensive one—was to get it from the quarry to the Nile, where they would load it on a barge for shipping to Thebes or elsewhere. As daunting as it would have been to haul away the Unfinished Obelisk, at least its movers wouldn't have had to go too far: The Nile lies only a few hundred yards from the granite quarry. And it would have been all downhill, along a series of road-like embankments the Egyptians built expressly for the purpose. But what if you were pharaoh and you wanted your obelisk fashioned out of the handsome red quartzite found in the Gebel Simaan quarry west of Aswan? Gebel Simaan lies far out in the desert, on a plateau several miles west of the Nile. How could your workers possibly convey such a gargantuan stone that far? To investigate this question, I traveled yesterday to the quarry, where another unfinished obelisk—this one the work of Seti I (1318-1304 B.C.)—lies abandoned in the sand. The only way to get to Gebel Simaan is by camel, so that's what I took. First I hired a boat to take me across the river to a camel staging area on the west bank. There, several dozen saddled dromedaries, the one-humped camels of Africa, stood or sat gawkily in the hot sand, blinking away flies wallowing in the viscous fluid of their enormous eyeballs. My camel driver was a Nubian named Mohammed. (Nubians are the people of southern Egypt and northern Sudan.) With a gesture from Mohammed, I threw one leg over the saddle. Then, with a lurch that almost sent me cartwheeling over its head, the camel heaved itself up onto its feet with a grunt, and I was off on my "ship of the desert," as the Arabs call the camel. Rambo—for that was the creature's name—immediately recognized that I was a camel-riding ignoramus. Without the periodic "Hut! Hut!" of Mohammed, who flopped along in his plastic sandals just behind us, Rambo would have come to a stubborn stop. Sometimes he did anyway, voicing his anger with a phlegmy hack like that of the Wookie in Star Wars. Now and then, I got back at him and his insolence by clicking on and off my tape recorder while taking notes; the unnatural sound spooked him a bit, I think.

The landscape grew steadily more striking. As soon as we got past the ruins of the 6th-century monastery of St. Simeon, which overlooks Aswan from a sandy ridge, great vistas of golden sand swept off uphill, broken only by occasional outcrops of eroded rock. Here and there, a towering wave of dune, its smooth sides rippled like the surface of a lake, hung in an eternal curl. Aswan vanished behind us, swallowed by intervening hills. With the sun hovering over my left shoulder like Big Brother, I fell into a kind of a trance while watching Rambo's lengthening shadow slide along the ground. I thought of that scene in Lawrence of Arabia in which Lawrence slips into his own trance while crossing the desert to Aqaba. Looking back at Rambo's rounded footprints in the sand, I was surprised at how much each resembled a pair of cartouches, the pharaohs' oval hieroglyphic nameplates. An endless string of nameless cartouches. When Rambo stepped past a bone bleached white as talcum powder, I said to myself, "Bones tell stories," then snorted at how absurd that sounded. Suddenly Rambo Wookied and jerked to a halt, startling me out of my reverie. I had dropped the rein, the end of which had fallen under his feet. Handing it back up, Mohammed shooshed Rambo back into haughty complacency, and we continued on.

Not much else is known about Seti I's obelisk. Why was it abandoned? Where did the pharaoh intend it to stand? What happened to the rest of the shaft? Was its stone appropriated for other building projects, or perhaps reshaped into a smaller obelisk? Musing on these unanswerable questions, I wandered about the site, stepping amidst a pastiche of potsherds, bird tracks, and camel dung. It was not until I clambered atop an outcropping that I noticed the road. That's right, way out there in the desert, a broad, paved road of rock-thickened sand. It swept in from the direction we'd come right up to the obelisk, as if built just for it. How had I missed it? By walking right along it as we approached from the east, I'm embarrassed to admit.

As we started home, I noticed that the road ended at the edge of the plateau, not more than a quarter mile from the obelisk. Did it disappear beneath the sand? Or would the Egyptians simply have rolled the obelisk down the sandy hillside toward the Nile? Two miles lay between us and the river. How many laborers might it have taken to move it that distance? We have one clue. Records show that Ramses IV dispatched an expedition to Wadi Hammamat in southeastern Egypt to procure some monumental stone. When it set out, the party numbered more than 9,000 men:

One line from the list keeps jumping out at me: "Dead (excluded from total)." The list reveals not only how many people were needed for such an excruciatingly difficult enterprise, but also how many of them perished in the undertaking. How many Dead (excluded from total) did the road to Gebel Simaan claim, I wonder? At dusk, we rounded the barren mountain Qubbet el-Hawa, or "Dome of the Wind," and descended the final slope to the Nile. The vanished sun still caught wispy clouds high overhead. Before hopping on the boat for the trip back across the river, I shook hands with Mohammed, paid him off, and cast a final sneer at Rambo.

Peter Tyson is Online Producer of NOVA. Obelisk Raised! (September 12) In the Groove (September 1) The Third Attempt (August 27) Angle of Repose (March 25) A Tale of Two Obelisks (March 24) Rising Toward the Sun (March 23) Into Position (March 22) On an Anthill in Aswan (March 21) Ready to Go (March 20) Gifts of the River (March 19) By Camel to a Lost Obelisk (March 18) The Unfinished Obelisk (March 16) Pulling Together (March 14) Balloon Flight Over Ancient Thebes (March 12) The Queen Who Would Be King (March 10) Rock of Ages (March 8) The Solar Barque (March 6) Coughing Up an Obelisk (March 4) Explore Ancient Egypt | Raising the Obelisk | Meet the Team Dispatches | Pyramids | E-Mail | Resources Classroom Resources | Site Map | Mysteries of the Nile Home Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule About NOVA | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Jobs | Search | To print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated November 2000 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Rambo at the camel staging area along the Nile.

Rambo at the camel staging area along the Nile.

Seti I's unfinished obelisk lies abandoned in the

desert several miles west of Aswan.

Seti I's unfinished obelisk lies abandoned in the

desert several miles west of Aswan.

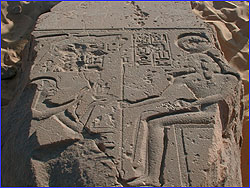

Hieroglyphic carving on Seti I's fragmentary obelisk.

Hieroglyphic carving on Seti I's fragmentary obelisk.

The ancient road at Gebel Simaan, with the broken

obelisk in the foreground.

The ancient road at Gebel Simaan, with the broken

obelisk in the foreground.

Will the NOVA obelisk stand upright on this granite

plinth in a few days?

Will the NOVA obelisk stand upright on this granite

plinth in a few days?