|

|

|

Mark Lehner, Archaeologist NOVA: Can you describe what your every day work is like, when you're not called off to Egypt to help raise an obelisk? LEHNER: I'm an archaeologist and I study ancient Egypt. I work at the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago and the Harvard Semitic Museum. When I'm not doing field work or lecturing, I prepare the maps and drawings of all the excavations we've done. I'm working on a database of all the different kinds of ancient material that we excavate—ancient bones, animal bones, ancient plant remains, pottery, artifacts, mud sealings. And I'm working on a complex topographical model of the Sphinx and the pyramids on the Giza plateau. I'm looking into many other research reports on excavations of other sites in Egypt—some close in time to when we're digging, and some of periods that are far later—for parallel structures. If we find a bakery, what do other bakeries look like? If we find a copper working shop, what do other copper working shops look like? I'm also doing very general reading about Egyptologists' interpretations of Egyptian society, how they organize themselves for big projects, whether it's the pyramid age or thousands of years later, say in Tutankhamun's time. I'm trying to understand what their society was like; it helps me think about the material that we're finding. NOVA: Have you had any previous experience on a project like this one? LEHNER: I was part of the NOVA team that successfully built a small-scale pyramid, using tools that would have been available to the ancient Egyptians, and I was also part of the NOVA team that unsuccessfully tried to raise an obelisk back in 1994. This is our second chance.

LEHNER: I think it's pretty important, in the way of putting the brakes on the other experts. Just one example of that is diamonds. One of the questions we're going to be looking at is, how did they cut granite? Diamonds are used in modern saws for cutting granite. So, some experts have concluded, even those who have worked in Egypt, that they had to have used diamond. The archaeologist immediately thinks along the following lines: All right, how much granite were they cutting? How many hieroglyphs were they cutting? How many obelisks and statues? And how many diamonds would they have required? Where would they get diamond? Where is diamond located as a natural resource? What does it take to get it? Was there any word for diamond? And is there any evidence that Egyptians went that far? We also look at representations of ships, of the pharaoh Hatshepsuts' ship, in particular, carrying an obelisk on a big barge. What do art historians who are also Egyptologists say about the extent that we can trust the way Egyptians show things as being realistic depictions of the way they actually did things? NOVA: Can you give us an example?

NOVA: What about the actual raising of the obelisk? Are there depictions of that? LEHNER: This is something that lay people ask all the time, not just about obelisks but about the pyramids: Why don't they show them building it? And somehow, Egyptologists are so used to this that they would be totally amazed if Egyptians did show themselves building something. Egyptians didn't choose to show these things as structures of their creation. They always emphasized that it was done according to a divine plan. It's my interpretation that they didn't show these things because they didn't want it to be the work of humans. They wanted it to be a thing that was divine. They also liked the idea that once something was created, it was instantly old, because divine things, in a sense, are very hoary and old. They'll say of a temple that it was laid out according to a plan that was devised in the time of the gods, so to speak. That's my take on it. NOVA: What about your understanding of how people were organized? How will that help in the actual raising of the obelisk? LEHNER: Well, there's some issue there. I have some questions in my mind, because there's a model of coercive forced labor, on a military scale, and there's a model of households turning out—as in the NOVA program about building the Incan bridge—where it's kind of a festival. I think it gets a bit ambiguous. In the age of the pyramids I'm really curious as to how much natural communities were turning out labor for it, rather than it being a huge Stalinist kind of cooperative forced-labor situation. The massiveness and difficulty of the project make us think coercion, but the care with which it's finished, and that includes obelisks, makes us think conscientiousness, or conscience. Therein lies the paradox.

LEHNER: I think we have some really good people this year. I think Owain Roberts is enormously insightful. He will look at the knots tied in rope that once held the Khufu ship together, and he will say things like, "there's a whole range of thinking in those knots." So, he looks at knots and, almost like a clairvoyant, he's reading a way of thinking. And I think rope was the linchpin of just about all of this—obelisks, pyramids, and so on. Engineers Mark Whitby and Henry Woodlock, they're the ones you've got to hold in check. They want to get very clever, in an engineering way. But if you hold them in check and say, "Well, hold on there," I think they're very insightful—they're trained engineers. They know where the center of gravity is. They know why you don't actually tip the obelisk on its center of gravity; you tip it a little ahead of its center of gravity so that the center of gravity acts as a brake, and that kind of thing. NOVA: But you say to the engineers, "Hold on, the Egyptians wouldn't have done it this way, because of...." LEHNER: Well, because engineers want to get clever, and they want to gain advantage. That's the engineer's whole thing. So, for example, Mark Whitby was very keen on raising the obelisk up and having a big heavy block on it that slides to the end and tips the obelisk down, like the old scales when the doctor weighed you and he tipped the little weight over? NOVA: Like the method Mark Whitby used to raise the stone in the NOVA Stonehenge project? LEHNER: Exactly. And I'm saying that that seems just a little too tricky. First of all, you've got to get this ten-ton block up on top of a 400-ton obelisk, or however many tons the block was. Why can't you just pull the nose of the obelisk down with ropes on the butt end? And in the conversation, Mark actually said, "Well, because you can't do this with ropes," Owain said, "No, wait a minute, sure you can, they do it in boats all the time." So that's how the whole technique that we're going to use evolved. NOVA: It sounds like a really great team.

NOVA: What do you think is the most difficult aspect of this whole project? LEHNER: Well, one of the most difficult aspects is actually getting a big obelisk—that's no easy thing. And it's just a wonder that they were able to get such huge pieces without fissures and cracks, because we're being challenged to do it with modern quarrymen, with modern flame jets and pneumatic drills. The other most difficult aspect is actually tipping the obelisk without losing control, using some kind of a mechanical advantage—whether it's a height and a pivot. And then, in our day and age, a very difficult thing is the safety of everyone involved. I think maybe the priorities would have been different in ancient times. Finally, a difficult thing is doing it within the film production schedule. I don't think that would have been a priority in ancient times either. NOVA: Do you think that the way you're going to try to raise the obelisk this time was the way the Egyptians did it? LEHNER: Well, you know, it's very hard to know, because you can only go so far in the evidence—the positions of the obelisks that are standing, the bases, the turning grooves—and then you're sort of out in the realm of, "It could have been done this way." I think it's very possible, however, because one of the insights that's come to me is that they probably wouldn't have gone too far out ahead of the most complex technological ensemble that they had in their everyday life, and that would have been in nautical technology—in their boats and in their seagoing ships, where they were using something like an A-frame for a mast—and using a lot of the mechanical advantages of rope and windlasses and so on. It's the kind of knowledge that Owain Roberts brings to the project. NOVA: What do you expect to learn from this experience? LEHNER: All kinds of things. I expect to learn a lot from Owain Roberts about the mechanical advantage you get from rope. Obviously, what we're doing is very audacious, to go out and actually carve these things and try to do these things. I know a lot of experts think it's popularizing and therefore not really a scholastic endeavour. In fact, it is; I think we're learning a lot from it. I think it's a learning experience for everybody. And that's the neat thing about these NOVA ancient technology films. They really are a learning experience, even for the experts involved, as they are for the audience. NOVA: What odds do you give the project of succeeding this time? LEHNER: If we actually get a big obelisk out, or even replicate one in cement, if necessary, I'd give the project pretty good odds of raising it, with the combined expertise. But it also makes you wonder how many times the Egyptians experimented and tried and failed, before they got it right. Explore Ancient Egypt | Raising the Obelisk | Meet the Team Dispatches | Pyramids | E-Mail | Resources Classroom Resources | Site Map | Mysteries of the Nile Home Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule About NOVA | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Jobs | Search | To print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated November 2000 |

Mark Lehner

Mark Lehner During the 1994 attempt to raise an obelisk, Mark

Lehner demonstrated one possible way the ancient

Egyptians carved hieroglyphs.

During the 1994 attempt to raise an obelisk, Mark

Lehner demonstrated one possible way the ancient

Egyptians carved hieroglyphs.

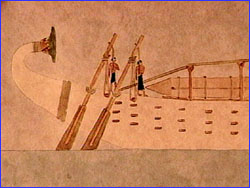

This modern depiction of the pharaoh Hatshepsut's

obelisk barge, drawn from a faded painting on her

mortuary temple in Luxor, offers one of the few clues

left by the ancients as to how they transported their

obelisks.

This modern depiction of the pharaoh Hatshepsut's

obelisk barge, drawn from a faded painting on her

mortuary temple in Luxor, offers one of the few clues

left by the ancients as to how they transported their

obelisks.

Mark Lehner hefts a dolorite stone that the ancients

used to quarry granite.

Mark Lehner hefts a dolorite stone that the ancients

used to quarry granite.

Mark Lehner shares a laugh with stonemason Roger

Hopkins.

Mark Lehner shares a laugh with stonemason Roger

Hopkins.