|

From the eighth to 11th centuries, as Norsemen from Scandinavia conducted raids

into Europe and elsewhere, they became known as Vikings—named after a

place called viken in the Oslo fjord. Over time, the word viking

became synonymous with piracy, and the Vikings garnered a reputation as brutal

plunderers that endured for a thousand years. But as archeologist William

Fitzhugh makes clear in this interview, their sordid reputation wasn't entirely

warranted. Fitzhugh, who curated a major retrospective at the Smithsonian

Institution, has done much to dispel myths and broaden understanding of the

Vikings. Here he offers his insights into what drove the Vikings on their

global explorations, how Norse scholars today view the Vinland Map, and

more.

Brutality in a brutal age

Brutality in a brutal age

NOVA: What did the Vikings actually do in their attacks into Europe?

Fitzhugh: Well, the attacks were very diverse. One misconception we

have is that swarms of Vikings raided constantly all over the place, and it

really wasn't that way. For the most part, the raids were totally independent.

They were not the result of national armies or navies moving down into Europe,

but rather the actions of individual Viking chieftains who grouped together

followers and had one or maybe several boats. Occasionally, as in some of the

invasions of Normandy, they organized whole flotillas and made a purposeful

kind of attack, but generally they were much more individualistic. They had to

find food, and they couldn't carry their food with them. They had to live off

the land, so they drove people out and took whatever money and other valuables

people had. And, of course, the church centers and monasteries like Lindisfarne

[a monastery in Northern England that Vikings pillaged in A.D. 793] constituted

the major sources of wealth at that time.

NOVA: What must it have been like for the monks at Lindisfarne to be suddenly

attacked out of the blue?

Fitzhugh: For them, the attack represented the vengeance of Satan on the

Christian outposts of Europe. It was a terrible event, because the monks and

the church centers had set themselves up in small, fortress-like places where

they could pursue their studies and writings in peace, and it was an invasion

of the sanctitude of Christ and their religion. This was totally unlike

anything that had happened before. There had been outlaws, but to have

shiploads of brawny characters show up at your isolated, supposedly sacred

center, this was the ultimate horror.

NOVA: Did they kill a lot of people in their various raids?

Fitzhugh: In many cases they did. I think they were relatively ruthless, but

remember, this was a ruthless age with far more than just peaceful farmers

living peaceful lives. All sorts of things were going on in the British Isles

and mainland Europe, including constant battles between rival princes vying for

kingship and control of local regions. The Vikings were just another crowd,

though a crowd that was non-Christian and had no compunction about killing

churchmen or women or children.

“They weren’t out to kill everyone in the countryside but rather to find a way

to live, to set up shop...”

That said, in general I think the victims were men, because the Vikings were

great at absorbing people. They needed slaves, they needed people to help row,

they needed people to help maintain their lifestyle. They regularly set up

small villages and centers where they could overwinter or stay for months at a

time, and they needed people to help run these establishments. So I think if

you were able to put yourself back into the camp of a raiding Viking group, you

probably would find Italians and Spaniards and Portuguese and French and

Russians—a very diverse group built around a core of Vikings from a

particular region, say, southern Denmark or an Oslo fjord. It wouldn't just

be blond, blue-eyed Norsemen.

A distorted history

A distorted history

NOVA: What are the main challenges in finding the truth about the Vikings?

Fitzhugh: Well, one of the major problems in Viking studies is that we're

biased towards the historical accounts—early chronicles that all came

from the church centers or official reports to the kings or regional

authorities. It's always been that way. Only in the past 20 years or so have

archeological and other studies begun to provide information that fleshes out

and in some cases contradicts or even replaces the historical record. These

findings are giving us a totally different view of the Vikings. We see them

archeologically not as raiders and pillagers but as entrepreneurs, traders,

people opening up new avenues of commerce, bringing new materials into

Scandinavia, spreading Scandinavian ideas into Europe. This contrasts sharply

with the early accounts. They were inevitably based on victims' reports and

were extremely one-sided.

NOVA: Are the Icelandic sagas as unreliable?

Fitzhugh: The Icelandic sagas are phenomenal documents that for hundreds of

years provided everything we knew about the Vikings. If we were interested in

Vinland [the Viking name for a far-off land they visited, which scholars now

believe is eastern Canada in and around Newfoundland], it was the sagas. If we

were interested in the history of the kings of Norway, it was the sagas. But

then, beginning with the discovery of Viking burial ships a century ago,

archeology started to poke its nose into Viking affairs, and today, excavations

have become an invaluable new source of information. Scholars have gone back to

the sagas and asked, "How much of this is history? How much fabrication? How

much just the elaboration of family storytelling?"

Current saga scholarship is wonderful, because it's giving us a lot of insights

as to why the sagas are the way they are. The sagas were compiled in the 13th

century and later based on stories that originated as early as 400 or 500 years

before that. This is a long time for an oral tradition to be handed down. Even

the Vinland sagas, which chronicle events around A.D. 1000, were not recorded

for a couple of hundred years after that. Some now believe the sagas are

basically family stories relating the ancestry, say, of Erik or of Gudrid and

her family. But archeology is actually proving that a lot of these stories have

a good basis in fact, so much so that Helge Ingstad could use them to find the

L'Anse aux Meadows site [an archeological site in Newfoundland believed to have

been a Viking settlement established hundreds of years before Columbus arrived

in America].

Vikings in North America

Vikings in North America

NOVA: Why did they abandon L'Anse aux Meadows?

Fitzhugh: Well, I think after a few years of using L'Anse aux Meadows as a

staging area, the Vikings simply found it untenable in terms of supporting a

sizeable group in that new environment. Too far from home, too many dangers. We

know from the sagas that they lost people, and they probably lost ships. L'Anse

aux Meadows reached a point where it had to move beyond the exploration phase

to the settlement phase, and that was not possible. We have to remember that

this was in the early days of the Greenland colony, which had only a small

number of settlers itself, and to have so much of its resources directed toward

a perilous new enterprise was not sensible. So I think the sagas are probably

correct when they say, "It's a beautiful, rich land, but we can't defend

ourselves in it."

NOVA: But this wasn't the end of the Norse in North America, right?

Fitzhugh: No. We've seen as a result of archeological research large amounts of

Viking material turning up in native sites in the arctic regions of North

America. This material dates to perhaps as much as 300 years after the initial

Vinland voyages. We seem to have a time period that began with the Vinland

contact episode, explorations, and so forth, and then after the society in

Greenland got rolling and people were settled, walrus-ivory trade with Europe

started to be really important. Probably more than any other factor, this

stimulated the continuous western orientation of the Greenland Norse, not only

up into the Greenland walrus-hunting territories but across the Davis Strait to

Ellesmere and Baffin islands and south into Labrador. These are areas where the

Vikings were exploring and trading, and where native populations were trading

Viking materials through their own trade networks. Of course, the continuing

need for wood in treeless Greenland prompted return visits to Markland, which

we know to have been today's Labrador.

NOVA: What happened to the Greenland colonies?

Fitzhugh: There are lots of different theories. This is a wonderful area of

exploration in terms of archeological and historical theory, because we have

environmental changes, we have growing human populations, we have an important

economic and climatic downturn. You see a society that is reaching a peak and

then just maintaining itself, but all the forces are going against it after

1300 or so. The western colony disappears around 1350. The eastern settlement

continues for another century, but it seems not to be doing too well, and then

it just drops off the line. The last historic record is from 1408, a church

wedding of Hvalsey. There are also theories of pirate raids and other kinds of

trauma that may have occurred in these settlements. All in all, I think we have

here a real human experience. This is not the wrath of God coming down, it's

not an Ice Age descending. When pondering this extinction story, one has to

consider a multiplicity of factors.

The map that unleashed a fury

The map that unleashed a fury

NOVA: When Yale first publicized the Vinland Map in 1965, was it a surprise

to most Norse scholars?

Fitzhugh: The publication of the Vinland Map was a total surprise to all

scholars, as it had been kept completely under wraps between the time it was

acquired by Yale [in 1959] and the publication of the Yale Press book. Only a handful of

Yale's inner circle and a few others knew about it. This was a major point of

concern among historical cartographers as well as archeologists, since the

publication of the map came as a public fait accompli before the scholarly

community had had a chance to consider its veracity in the normal vetting

process. It was, in fact, a slap in the face of the scholars most knowledgeable

about medieval cartography.

NOVA: You were a young archeology student at the time. Do you recall your

personal reaction?

Fitzhugh: I was still only a neophyte in northern archeology and not even in

graduate school. At the time, I was in the U.S. Navy cruising off the east

coast of Greenland, and I was simply incredulous. Of course, like everyone

else, I believed it and only later began to hear about the astonished scholarly

reactions. It actually took several years before the publication's evidence

began to be assessed and rejected by most specialists.

NOVA: Among Norse scholars today, what's the general consensus about the map?

Authentic medieval document—or a great hoax?

Fitzhugh: Today's scholarly community is almost universally united in its

condemnation of the map and the process by which it was published. The problem

has been that during the past couple of decades there have been numerous

studies that have taken pro and con stances, each validating report stimulating

a succeeding contrary view. So only the most serious students of the Vinland

Map have been able to keep up with events. The fact that [Norse historian]

Kirsten Seaver has spent a decade parsing the issues in a Stanford University

Press book is an indication of the general academic view.

“When we look into the future now, I think we implicitly look back to the

Vikings as the origin of this kind of human endeavor to find new

horizons...”

At present there are only one or two scholars arguing in its favor, and even

they admit that their studies do not prove the Vinland Map is genuine. They

only show that it is presented on an old piece of parchment and could be

genuine, or that early inks might have had ingredients similar to the ink on

the Vinland Map. In fact, almost all serious scholars now believe it is a hoax

but despair of ever being able to prove it conclusively. It is one of those

great cases of a story being kept alive by the persistent efforts of a few

"true believers" who refuse to accept the obvious.

End of an era

End of an era

NOVA: What contributed to the end of the Viking age?

Fitzhugh: The end probably came about as a result of tired Vikings who had

become citizens of many places in Europe. They had become Christians back in

their homelands, kings had evolved and were instituting taxes, and the economy

had become such that you could get along much better as a trader rather than as

a raider. The force of Viking onslaughts had caused European kingdoms to become

centralized and focused. They had basically gotten their act together, learning

how to defend themselves and to gain by trading and negotiating with the

Vikings rather than just trying to fight them.

NOVA: What was it about the Vikings that made it so easy for them to assimilate

into foreign cultures?

Fitzhugh: I think the Vikings were very adaptive. They learned to take

advantage of whatever situation they found themselves in. When they settled in

Europe, they took farmlands, yes, but they also met new people; they took

slaves, but the slaves became part of their families. Their languages were not

that different; they were all Germanic-based languages. (Many of the

place-names in the British Isles, in fact, date from Viking times.) And the

Vikings were not on a special crusade. They weren't trying to bring paganism to

Europe. Quite the opposite, in fact: They were receiving influences from a

Europe that they saw as somehow technologically and maybe in some ways

politically superior. They weren't out to kill everyone in the countryside but

rather to find a way to live, to set up shop, and I think they just readily

mixed in.

NOVA: In the end, what do you feel was the Vikings' greatest impact on the

world?

Fitzhugh: I think that without question it was reconnecting humanity, making

the world a smaller place by travelling huge distances, connecting peoples from

Baghdad to Scandinavia to southern Europe to the north Atlantic to the mainland

of North America.

From a social or economic or religious point of view, no matter what you think

of it, the Viking period was a kind of hinge in European history. It was the

time you went from early history and classical civilization into what we know

as modern Europe and a modern world, in which people are exchanging ideas and

moving around rapidly and exploring new frontiers, looking for new resources

and new connections. When we look into the future now, I think we implicitly

look back to the Vikings as the origin of this kind of human endeavor to find

new horizons, go new places, use new technology, meet new people, think new

thoughts.

In a millennium era as we're in now, this is the inspiration of the Vikings:

It's not only the historical impact that they had on Europe and in discovering

the North American continent for the first time. These things are interesting

and important, but I think that we should look at the Vikings in a broader

sense, as a kind of a human myth come true that we can draw on—that is,

we can look to space, to the oceans, to explorations among our own peoples,

finding new ways of getting along, mixing, and sharing.

|

William Fitzhugh, curator in the Department of Anthropology at the

Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History, says the Vikings were far

from simply brutish barbarians in horned helmets.

| |

While ruthless, Viking attacks were more about survival than subjugation,

historians now say.

| |

A typical Viking settlement would not have contained blond, blue-eyed Norsemen

alone, but a cosmopolitan group of inhabitants.

| |

With new archeological evidence at hand, scholars are trying to separate fact

from fiction in the Icelandic sagas.

| |

Viking merchants continued to trade and hunt in American waters long after

their compatriots abandoned their Newfoundland toehold.

| |

Erik the Red's Greenland colonies succumbed to a synergy of forces working

against the Viking settlers.

| |

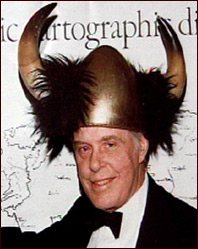

At the party celebrating Yale's unveiling of the map, Alexander Vietor, curator

of Yale's map collection, playfully donned a helmet sent by the King of

Norway.

| |

The Norsemen did things their own way, including building graves in the shape

of boats, but they also readily absorbed outside influences.

| |

|