|

The art of forging literary and historical documents is nearly as old as

writing itself. Two thousand years ago, early practitioners put reed pens to

papyrus to mimic the writing of Socrates and other ancient authors whose work

was highly valued. Today, the motive of most forgers remains the

same—create something "priceless," then find a sucker willing to pay an

exorbitant price. Yet as this collection of famous fakes illustrates, sometimes

the forger's aim is not profit but power, and even a crudely executed forgery

like the Protocols of the Elders of Zion can have devastating, long-term

consequences. To learn the details of this and other cases, click on the links at right or simply scroll down through the gallery of forgeries.—Susan K. Lewis

|

|

|

A medieval fresco at the Church of Santi Quattro Coronati in Rome depicts

Constantine's generous, but fictitious, donation.

| |

Donation of Constantine

This ancient letter, which helped bolster the Catholic Church's power for

roughly 700 years, was probably the first forgery to significantly impact the

course of history. Allegedly sent by the Roman emperor Constantine the Great to

Pope Sylvester I in the fourth century A.D., the letter testifies to the

emperor's conversion to Christianity and grants vast authority to the pope and

his successors. Among other privileges, the emperor gives the pope dominion

over "Rome and the provinces, districts, and towns of Italy and all the Western

regions."

Constantine's conversion is an historical fact, but the letter is a pure

fabrication. While its origin is debated, the Donation was likely

concocted between A.D. 750 and A.D. 850, perhaps by a church official. Various

popes used it over the ensuing centuries to defend their political power, and

the Donation was even celebrated in a painting in the Vatican. It was

revealed as a fake in the 15th century.

|

In the preface to this 1832 edition of the script, Ireland admits his guilt.

| |

Shakespeare's Lost Play

After passing off as genuine what were counterfeit fragments of the scripts of Hamlet and

King Lear he claimed were penned by the bard himself, late 18th-century

forger William Henry Ireland became foolishly daring. He announced the

discovery of a completely unknown Shakespeare drama called Vortigern.

Thrilled by the thought of a new Shakespeare, a renowned theater producer

signed on to premier the play at Drury Lane. But when Ireland handed over the

text, his game was up. The producer quickly came to suspect that the hackneyed

script was written by Ireland himself. Not only did he refuse to bill it as a

Shakespeare original, but he planned to stage the play as an April Fool's Day

joke—along with a musical farce about the gullibility of an art

collector. The play eventually premiered a day late, on April 2, 1796.

|

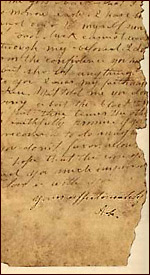

The unknown author made little attempt to match Lincoln's handwriting, let

alone his refined prose.

| |

Lincoln's Love Letters

The stumbling, awkward English in this exchange of letters would have

horrified Abraham Lincoln, a master of prose with impeccable grammar. The

letters are supposedly between Lincoln and his real-life clandestine love Ann

Rutledge. In them, "Beloved Ann" professes, "if you git me the dictshinery...I

no I can do both speeking and riting better...my hart runs over with hapynes

when I think yore name..." While slightly more literate, "Lincoln's" letter to

Rutledge is peppered with anachronisms and signed "yours affectionately,

Abe"—a nickname the proper Mr. Lincoln abhorred.

Despite the crude nature of the forgeries, The Atlantic Monthly

published a series of articles based on them entitled "Lincoln the Lover: The

Courtship," in January 1929. As soon as the articles went to press, several

Lincoln scholars, including biographer Carl Sandburg, identified the letters as

outlandish fakes.

|

Newsweek proclaimed in its May 2, 1983 issue that the "secret diaries" could

"rewrite history."

| |

Hitler's Diaries

Kenneth Rendell, a dealer in historical documents who helped unmask the

Hitler diaries, called them "bad forgeries but a great hoax." The hoax began in

1981, when a reporter for the German magazine Stern caught wind of

diaries recovered from a Nazi plane crash and stowed away for decades. Over 50

journals, purportedly handwritten by Hitler, revealed a kinder, gentler

dictator whose "final solution" to the "Jewish problem" was not genocide but

merely the deportation of Jews.

Stern hired experts to authenticate the diaries but gave them only a few

select pages to review. Even worse, many of the examples of "genuine" Hitler

documents Stern provided for comparison were from the same dealer who

had proffered the diaries. They were, of course, all in the same

hand—that of the forger.

When Stern broke the story of the diaries in late April of 1983, it

triggered banner headlines around the world. But they were soon revealed as

fakes. At his trial, forger Konrad Kujau, a German dealer in military

memorabilia, openly admitted guilt and gladly signed Hitler "autographs" for

the crowd.

|

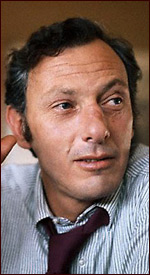

Clifford Irving, photographed in February 1972, as his forgery scheme was

unraveling.

| |

Howard Hughes's Autobiography

Even the most brazen forgers don't usually ape the writing of a living

subject. But Clifford Irving went even further, composing an entire

"autobiography" of Howard Hughes in 1971 while Hughes was still alive. Irving

miscalculated that the reclusive 65-year-old billionaire, who hadn't appeared

in public since 1958, would be too ill to step forward and call his bluff.

Together with his wife Edith, Irving forged not only the autobiography but also

correspondence with Hughes discussing the book and various legal documents. The

contract Irving and "Hughes" signed with McGraw-Hill guaranteed an advance of

$750,000 for the manuscript.

Just before the book was to be published in 1972, the real Hughes did come

forward—if not in person at least in a telephone call with

reporters—to expose the fraud. Irving was sentenced to two and a half

years in prison, but he later cashed in on his escapades with an authentic best-seller entitled The Hoax.

|

Details in the diary hinted that "Jack the Ripper" was James Maybrick, a

Liverpool cotton merchant and arsenic addict.

| |

Jack the Ripper's Diary

A publicity brochure for The Diary of Jack the Ripper declared

October 7, 1993 "the day the world's greatest murder mystery will be solved."

On that day the book, which already had advanced sales of over 200,000 copies,

would be available to countless fans of the true-crime genre in England, the

U.S., Australia, continental Europe, and Japan.

The gruesome diary's author wrote, "I place this now in a place where it shall

be found," yet it apparently took more than 100 years for it to emerge. In

1992, an Englishman named Mike Barrett announced he had acquired the diary from

a deceased friend and had deduced the real identity of its author.

When forgery expert Kenneth Rendell analyzed the diary, he was struck by the

handwriting style, which seemed more modern than Victorian. It was written in a

genuine Victorian scrapbook, but 20 pages at the front end had been torn out,

as if a forger had removed pages used by the scrapbook's original owner.

Rendell and other experts ruled the diary a fake, but the book's British

publisher went ahead with its release, noting the diary's dubious authenticity

only on the dust jacket.

|

Mussolini strikes a pose before an Italian audience in 1934. His forged

diaries had a similarly forceful and convincing style.

| |

Mussolini's Diaries

One of the experts who authenticated the diaries of Italian dictator Benito

Mussolini when they emerged in 1957 was emphatic: "Thirty volumes of

manuscripts cannot be the work of a forger," he declared. "You can falsify a

few lines or even pages, but not a series of diaries." Yet an Italian woman

named Amalia Panvini, aided by her 84-year-old mother, had done just

that—producing masterful forgeries that fooled even the dictator's son,

Vittorio.

Italian police confiscated most of Panvini's prolific output. But 11 years

later, despite the widely publicized forgery case, the Sunday Times of

London purchased four remaining volumes for a sizeable sum. Fortunately, the

Times's editors caught their mistake before publishing the fakes.

|

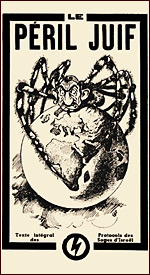

The Protocols have spurred anti-Semitism in many different languages

over the decades.

| |

Protocols of the Elders of Zion

Hitler and his fellow Nazis used a preposterous forgery from

late-19th-century Russia as a brutal weapon of propaganda against the Jewish

people. An agent of the Imperial Russian secret police had devised the

Protocols in the 1890s both to demonize Jews and to target Russia's

minister of finance, Sergei Witte, whose policies threatened many conservative

Russians. The Protocols link Witte with a Jewish conspiracy to

destabilize governments and take over the world, a mission supposedly plotted

at a clandestine meeting among Jewish leaders in Basel, Switzerland in 1897.

The Protocols, the "minutes" from this fictitious meeting, were first

published in full in Russia in 1905, but tens of thousands of copies soon

spread throughout Europe and the U.S. In August 1921, the London Times

exposed the Protocols as a forgery, but this didn't stop Hitler and

other anti-Semites from using it as fuel in their war of hatred. Joseph

Goebbels, who helped orchestrate the Nazi propaganda campaign, had the

Protocols translated into many languages and widely distributed. Even

today, the infamous forgery remains in circulation among the Ku Klux Klan and

neo-Nazi groups, and it continues to inflame anti-Semitism around the world.

|

|

|