Black Ink

When researchers at the British Museum first subjected the faded black pigment

to scientific scrutiny in 1967, they were struck by how different it seemed

from most medieval inks. Medieval iron-gall inks, including those used on the

Tartar Relation and Speculum Historiale, usually appear dark

under ultraviolet light, but this pigment fluoresces. In the 1990s scientists

Robin Clark and Katherine Brown, using a newly developed technique known as

Raman probe spectroscopy, confirmed that the pigment is carbon-based and unlike

the iron-based inks historians would expect to see on a genuine medieval

map.

Yellow-Brown Lines

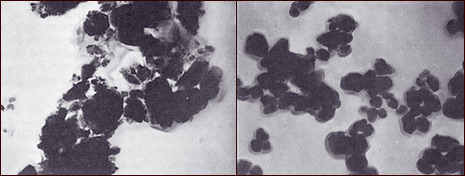

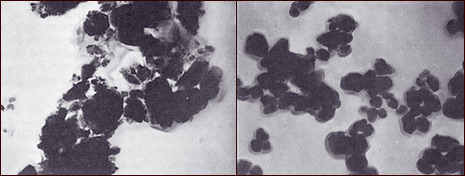

A debate has raged for decades over whether or not the yellow-brown lines of

the map hold the telltale sign of forgery. In the 1970s, researchers at Walter

McCrone and Associates, a firm specializing in chemical analysis, examined

ultramicroscopic samples from the yellowish lines. They identified crystals of

the mineral anatase in a particular rounded form that was manufactured only

after around 1920. In the 1980s, a group of researchers lead by physicist

Thomas Cahill of the University of California, Davis challenged the McCrone findings, suggesting that

the McCrone team mistakenly sampled paint that had fallen onto the inked lines

of the map from a modern ceiling. More recent work using Raman probe

spectroscopy has corroborated the McCrone discovery of the suspicious mineral

crystals.

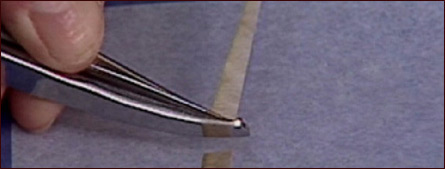

Off-Register Lines

The lines of the map appear aged and worn, yellow-brown in color with flakes of

black pigment on top. Was the map drawn with a single application of black ink,

most of which flaked off, leaving behind a yellow-brown stain or binding agent?

Or, as chemical analyst Walter McCrone asserts, did a forger mimic this effect?

At one spot on the west coast of Great Britain, the yellow-brown and black

lines appear out of register. Smithsonian scientist Kenneth Towe points to this

as evidence that the yellow-brown line was drawn separately. Researchers at the

University of California, Davis who defend the map's authenticity counter that this is the only

place on the map where the lines don't match up and that it could be the mark

of a medieval scribe retracing a sketchy line with fresh ink. Even some

skeptics of the map reject the idea of a "double-inking."

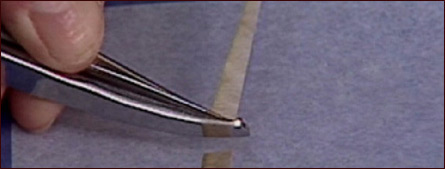

Parchment Date

The map is drawn on parchment, animal hide that can be radiocarbon dated.

University of Arizona researchers, who had to destroy a sliver of parchment for

the test, selected a fragment at the bottom edge unmarked by text or drawing.

Their results dated the parchment to within 11 years of 1434, the time frame

noted by the map's defenders. But the test merely proved that the parchment was

medieval, not the ink of the map itself. A forger would likely have used an old

parchment to give his or her work an authentic air and could have even used parchment

from the Speculum Historiale itself, which appears to have at least one

section missing.

Atomic-Era Substance

The researchers who dated the parchment first had to clean off a carbon-based

coating either on the map's surface or embedded in its fabric. The exact nature

of this coating remains controversial, but it clearly contains carbon dating to

the mid-20th century. It appears to have been deliberately applied

to the parchment around the time of the map's emergence in the 1950s. The

atomic-era substance may simply reflect an undocumented attempt in the 1950s to

conserve an authentic medieval map, but it may also be a sign of forgery. If a

forger used a 15th-century parchment, he or she likely would have

scrubbed it clean of markings and then prepared a smooth surface on which to

draw, perhaps with this substance.

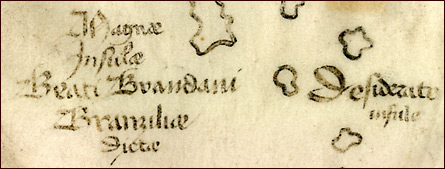

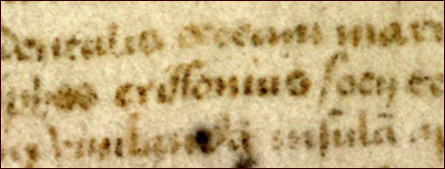

Vinland Text

The longest caption, and certainly the most discussed part of the map, claims

that Viking adventurers reached American shores hundreds of years before

Columbus. It was hardly the first such claim—two Icelandic sagas include

tales of Vinland, and a forger could have garnered details from these sagas and

other historical sources. The map's Latin text notes that Leif Eriksson was

together with a companion named Bjarni when he discovered Vinland, a curious

detail that Norse scholar Kirsten Seaver says runs counter to the information

in the sagas and originated with a history of Greenland written in 1765.

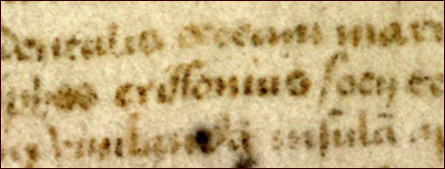

Skeptics of the map also point to the Latin translation of Eriksson

("erissonius") as a red flag. A medieval scribe would likely have used the

separate word "filius" for "-sson." The use of "-sonius" became common only

after 1600.

Island of Greenland

The appearance of Greenland as an island troubled even the experts who helped

"authenticate" the map for Yale in the 1960s. The Norse undoubtedly colonized

Greenland by A.D. 1000, but medieval Scandinavian accounts suggest that

Greenland was not perceived to be an island. An undisputed map from 1427

depicts Greenland as the end of a peninsula stretching toward the arctic north.

Arctic ice conditions made sailing along Greenland's northern coast

treacherous, if not impossible, and the first piecemeal circumnavigation of

Greenland was completed around the turn of the 20th century. What's more, the

outline of Greenland—with its detailed coastline—is suspiciously

similar to Greenland's depiction on modern maps.

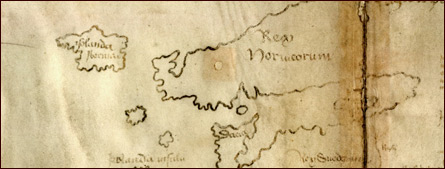

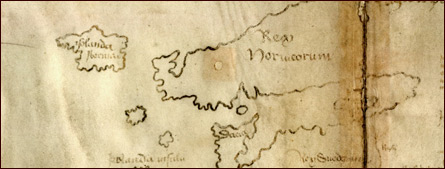

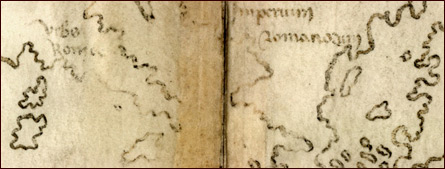

Scandinavia

It is odd that a map providing intricate details of Viking exploration depicts

the Viking homeland of Scandinavia in such a sketchy and inaccurate way. The

map shows Norway—Rex Noruicorum—as an immense peninsula

stretching over the Baltic Sea and wrongly locates Sweden—Rex

Suedorum—south of the Baltic. Defenders of the Vinland Map never

claimed that the map's author was Scandinavian, but they have suggested that

the medieval scribe used Scandinavian as well as Venetian maps as

references.

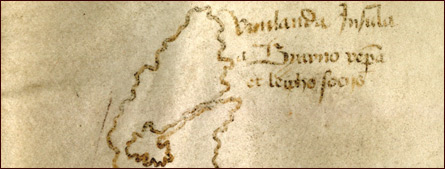

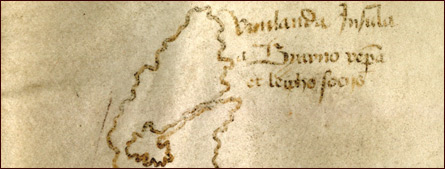

Vinland

This large island with two deep bays gave the map its name and propelled it to

fame and notoriety. To the right of the island, a Latin label reads, in

translation, "Island of Vinland discovered by Bjarni and Leif in company." The

Norse sagas tell of Vinland as a fertile place of wild grapes, but they offer

only a vague geographic description, lacking the quite specific details shown

on the map. It is also puzzling why a medieval scribe would have singled out

Vinland and not have included other locations in North America that the Norse

explored and later described in the sagas, such as Helluland and Markland.

Wormholes

Rare book collector Laurence Witten, who bought the map from an Italian dealer

in 1957, was thrilled to find that holes in it lined up with holes in the front

pages of the Speculum Historiale. In turn, a hole in the later

pages of the Speculum had a match in the front pages of the Tartar

Relation. This evidence, linking the map with two medieval documents,

helped seal Witten's sale of it to Yale for an undisclosed but exorbitant

price. The map's nine holes don't appear to have been made with a drill, and

some go directly through lines of ink. But skeptics point out that they are

located more in the center than at the edges of the map, where worms would

likely nibble. A forger could have bound the map together with the authentic

documents and then set some hungry worms to work. No one knows the age of the

holes.

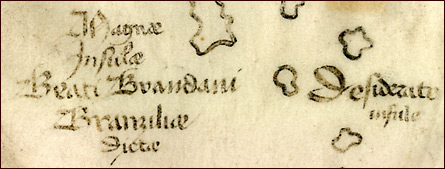

Handwriting

The Yale team that declared the map authentic in the 1960s believed it was

written in the same hand as the Tartar Relation and Speculum

Historiale, but others don't agree. When the map was shown to the Keeper of

Manuscripts at the British Museum in 1957, he rejected it in part because he

thought the handwriting had a 19th-century look. Several paleographers (experts

in ancient writing), including the woman who catalogued the map and the other

two texts for Yale in the 1980s, point to differences in the handwriting of the

map and its supposed companions. Kirsten Seaver goes further—spotting

similarities, including a horizontally looped "d" and a wavering tendency, in

both the map's writing and the hand of Father Josef Fischer (1858-1944), a

Jesuit expert on medieval geography whom Seaver considers the map's true

author.

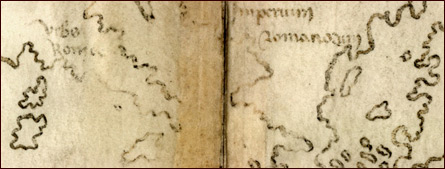

Page Fold

Whoever drew the Vinland Map appears to have done as much as possible to avoid

drawing across the page fold. Geographic names are positioned to either side of the

fold, rather than crossing it. The Adriatic Sea is even widened so that Greece

and Italy lie safely to the sides of the fold, and some European rivers appear

re-routed to avoid it. Knowing that the map would be folded, would a medieval

scribe have avoided marking this area? Or is this fold-avoidance a clue that a

modern map was made on an old piece of parchment, long after the fold crease

developed?

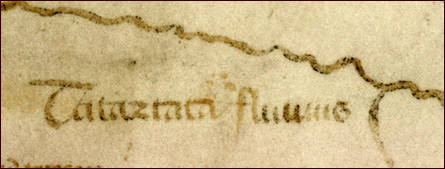

River Tatartata

This name, like many of the geographic labels on the map, appears to have been

copied from the first few pages of the Tartar Relation. On the first

page of this authentic text, two words, "tatar" and "tata," are next to one

another. Punctuation that should separate the two words is missing. The Vinland

Map author mistakenly joins them as one word on the map. Was this copying

mistake made by a medieval scribe or a 20th-century forger trying to

draw links between an authentic text and a forged map?

|

|