|

|

400 Years of Subs Introduction | 1580-1861 | 1861-1900 |1900-1918 1918-1939 | 1939-1945 | 1945-1972 | 1972-2000

Early in the Civil War, the Confederate government authorized citizens to operate armed warships as 'privateers.' A New Orleans consortium headed by cotton broker H.L. Hunley gained approval for the operation of Pioneer, a 34-foot-long submarine designed and built by James McClintock. The boat held three persons, one to steer and two to crank the propeller. In a March 1862 demonstration on Louisiana's Lake Pontchartrain, a submerged Pioneer sank a barge with a towed floating torpedo. In April 1862, the U.S. Navy captured New Orleans, and its builders scuttled Pioneer. Soon discovered, the boat was sold for scrap in 1868.

Villeroi obtained a contract from the U.S. Navy for a larger submarine, the 46-foot-long Alligator. Its propulsion was originally 16 oarsmen with hinged, self-feathering oars, but an improved version had a three-foot-diameter, hand-cranked propeller. Weapon: an explosive charge that a diver would set against an enemy hull. Alligator entered service on June 13, 1862, the first submarine in the U.S. Navy. Towed south from Philadelphia for operations in the James River, the boat proved too large to hide and support divers in the relatively shallow water, and it foundered and sank in a storm in 1863.

In Charleston, a team comprised of Dr. St. Julius Ravenel, David Chenoweth Ebaugh, and William S. Henery created the low-freeboard steamboat known as David (as in David and Goliath). It could either directly ram an enemy vessel or make use of a spar torpedo, an explosive on the end of a long pole. Spearheaded by Army Captain F. D. Lee, the Southern Torpedo Boat Company built several as a profit-making venture (anyone who could sink a blockading Union warship could earn substantial bounties).

Hunley's New Orleans consortium shifted operations to Mobile, Alabama, and built a second, slightly improved submarine, which may have been called American Diver. McClintock spent a lot of time and money trying to replace hand-cranking with some sort of electrical motor, but without success. This submarine sank in rough weather in Mobile Bay; the crew was rescued.

Hunley's consortium built a third submarine about 40 feet long. Crew: probably nine, eight to crank the propeller and at least one to steer and operate the sea cocks and hand pumps to control water level in the ballast tanks. The Confederates sent the submarine to Charleston to try to break the Federal blockade. It sank almost immediately, perhaps swamped by the wake of a passing steamer, and some crew members were lost. Confederate Commanding General P.G.T. Beauregard became disenchanted, but Horace Hunley persuaded him to allow "one more try" under Hunley's personal supervision. The boat sank again, killing Hunley and the crew.

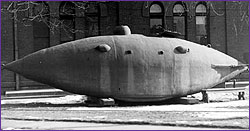

A group of Northern speculators formed the American Submarine Company to take advantage of a vote in the U.S. Congress to approve the use of privateers. However, when President Abraham Lincoln declined to accept the authority, construction of this consortium's submarine, the Intelligent Whale, languished. The boat was not completed until 1866, long after the war ended. The then ostensible owner, O.S. Halstead, made several efforts to sell it to the government, and the U.S. Navy finally held formal acceptance trials in 1872. The Intelligent Whale failed. Halstead was not present, having been murdered the year before by his mistress's ex-lover. 1863 The French team of Charles Burn and Simon Bourgeois launched Le Plongeur (The Diver). It was 140 feet long, 20 feet wide, and displaced 400 tons. Power: engines run by 180 pounds-per-square-inch compressed air stored in tanks throughout the boat. To operate it, crew members filled ballast tanks just enough to achieve neutral buoyancy, then made adjustments with cylinders that they could run in and out of the hull to vary the volume (Bourne's concept). Le Plongeur proved too unstable: A crew member's movements could send her into radical gyrations. 1864 On February 17, after months of training and operational delays, the spar-torpedo-armed CSS H.L. Hunley attacked the USS Housatonic, which bears the dubious distinction of being the first warship ever sunk by a submarine. Shortly after the attack, Hunley disappeared with all hands, not to be found until 1995 (by a team led by the author Clive Cussler), about 1,000 yards from the scene of action. With hatches open for desperately needed ventilation, the boat may have become swamped by the wake of a steamer rushing to the aid of the Housatonic. In summer 2000, Hunley was recovered and is now undergoing conservation and study. 1864 Wilhelm Bauer, a visionary ahead of his time, proposed powering submarines with internal combustion engines. All told, he spent 25 years developing (or at least proposing) submarines on behalf of six nations: Germany, Austria, France, England, Russia, and the United States. His plebeian origins and autocratic style, not to mention his lowly army rank, proved serious handicaps in dealing with the aristocratic brethren who ran most of the navies of the day. Essentially ignored by his native Germany in his lifetime, Bauer became a posthumous hero in the Nazi era. 1867 English engineer Alfred Whitehead developed a self-propelled mine, which he called the "automobile torpedo." This was the true ancestor of the modern submarine-launched torpedo. 1869 The U.S. Navy began manufacturing the Whitehead torpedo for use by both surface ships and a new class of vessel: the torpedo boat. This spawned the development of another new class, the torpedo-boat destroyer. Some navies flirted with yet another class, the destroyer of torpedo-boat destroyers. Whatever, surface-launched torpedoes had marginal military effectiveness and found their true home underwater. 1870 French novelist Jules Verne brought submarines to full public consciousness with Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, in which the despot Captain Nemo uses his submarine Nautilus to sink, among others, the then fictional USS Abraham Lincoln. Verne's research was impeccable: He even computed the compressibility of seawater—'0' for most purposes—to be a factor of .0000436 for each 32 feet of depth. 1870 The German Frederich Otto Vogel built a submarine but it sank during trials.

Recent Irish emigré and Patterson, New Jersey schoolteacher John Phillip Holland submitted a submarine design to the Secretary of the Navy, who passed the paperwork to a subordinate. No one would willingly go underwater in such a craft, that officer suggested, and, even if the idea had merit, he warned Holland, "to put anything through Washington was uphill work." 1878 Finding sponsorship with the Fenians, a group of Irish revolutionaries seeking a way to harass the British Navy, Holland built a small prototype submarine, Holland No. 1, to test out his theories, including the use of a gasoline engine. The trial was successful enough to encourage building a larger, more warlike boat (see 1881). 1879 Anglican Reverend George W. Garrett tested the steam-powered Resurgam, which relied on steam from a boiler for surface operations, steam stored in pressurized tanks for submerged operations. The boat passed initial trials but sank while under tow (it was rediscovered in 1996). Broke but not deterred, Garrett took his ideas to a wealthy Swedish arms manufacturer, Thorsten Nordenfeldt (see 1885). 1881 Holland launched the Fenian Ram, 31 feet long and armed with a ram bow and an air-powered cannon. The craft reached speeds of nine knots, depths of 60 feet, and stayed down for as long as an hour during tests, which took up to two years to complete. The Fenians became increasingly frustrated with Holland's delays and, faced with internal legal squabbles, stole their own boat and hid it in a shed in New Haven, Connecticut, where it remained for 35 years. Holland had nothing more to do with the Fenians, and the boat was eventually donated to the city of Patterson, where it is now on display in West Side Park.

Holland and several investors formed the Nautilus Submarine Boat Company, hoping to sell a submarine to the French, then at war in Indochina. The company launched its prototype, dubbed the Zalinski Boat, in 1885, but the vessel proved too heavy for the launching ways and smashed into some pilings. Her damage repaired, she made some token trial runs, but the war ended and the company went bankrupt.

French designer Claude Goubet built a battery-operated submarine that proved too awkward and unstable to meet with any success. He followed up in 1889 with Goubet II, also small, electric, and ineffective.

American Josiah H.L. Tuck demonstrated Peacemaker. It was powered by a chemical (fireless) boiler, with 1,500 pounds of caustic soda providing five hours of endurance. Tuck's inventing days ended when relatives, angered that he had squandered most of a significant fortune, had him committed to an asylum for the insane. 1885 Thorsten Nordenfeldt launched Nordenfeldt I - 64 feet long and armed with one external torpedo tube. It took as long as 12 hours to generate enough steam for submerged operations and about 30 minutes to dive. Plus, once underwater, sudden changes in speed or direction triggered, in the words of a U.S. Navy intelligence report, "dangerous and eccentric movements." Good public relations overcame bad design, however. Nordenfeldt always demonstrated his boats before a stellar crowd of crowned heads, and many regarded his submarines as the world standard. 1887 The U.S. Navy announced an open competition for a submarine torpedo boat, with a $2 million incentive. The Navy based specifications on presumed Nordenfeldt-level capabilities and a steam power plant packing 1,000 horsepower. Bidders included Nordenfeldt, Tuck, and Holland. Holland's design won, but because of contractor-related complications, the Navy withdrew the award. The Navy reopened the competition a year later, and Holland won again. But a new Secretary of the Navy diverted the $2 million to surface ships. Nordenfeldt lost interest in submarines, Tuck went into the asylum, and Holland got a job as a draftsman, earning $4 a day. 1888 Gustave Zede assembled Gymnote for the French Navy. A 60-foot, battery-powered boat capable of eight knots on the surface, the submarine was limited by the lack of any method for recharging the batteries while at sea. Her naval service was largely limited to experimentation. 1889 Spaniard Isaac Peral's Peral successfully fired three Whitehead torpedoes during trials, but internal politics kept the Spanish Navy from pursuing the project. 1893 With a new administration in office, the U.S. Congress appropriated $200,000 for an "experimental submarine," and the Navy announced a new competition. There were three bidders: Holland, George C. Baker, and Simon Lake.

1895 Taking a leaf from the Nordenfeldt playbook—in this case, good public relations to overcome political intransigence—Holland let it be known that he was entertaining offers from foreign navies. His tactic may have succeeded, for on March 3, the U.S. Navy awarded the John P. Holland Torpedo Boat Company $200,000 to build an 85-foot, 15-knot, steam-powered submarine called Plunger. 1897 Even before Plunger had failed, Holland began construction of a smaller (54 feet), slower (7 knots), gasoline-powered boat, Holland VI. Armament: one dynamite gun (air-launched, 222-pound projectile with seven loads) and a Whitehead torpedo (three loads). Crew: six men. Habitability: included a toilet to support operations as long as 40 hours. Holland began a series of public demonstrations. The New York Times, May 17, 1897: "The Holland, the little cigar-shaped vessel owned by her inventor, which may or may not play an important part in the navies of the world in the years to come, was launched from Nixon's shipyard this morning." 1898 The impending Spanish-American War intruded on Holland's efforts to sell his new boat to the Navy, although Theodore Roosevelt, then Assistant Secretary of the Navy, told his boss, "I think that the Holland submarine boat should be purchased." The war begun, Holland offered to go to Cuba and sink the Spanish fleet—on the condition, if he proved successful, that the Navy buy his boat. The Navy was properly horrified at the thought of a private citizen using a private warship to sink foreign ships; times had changed since Bushnell and Turtle and the days of the privateers. In September, Simon Lake's 36-foot Argonaut I made an open-ocean passage from Norfolk, Virginia, to Sandy Hook, New Jersey, prompting Jules Verne to send Lake a cable: "The conspicuous success of submarine navigation in the United States will push on underwater navigation all over the world . . . . The next war may be largely a contest between submarine boats."

The French fielded the 148-foot, 266-ton Gustav Zede, named for the recently deceased designer. On maneuvers, the submarine 'torpedoed' an anchored battleship to the consternation of some, and pride among other, French naval officers. The boat's success prompted an international competition for a submarine with a surface range of 100 miles and a submerged range of 10 miles. The winner (out of 29 entries) was Maxime Laubeuf's 188-foot, 136-ton Narval, which began life with a steam engine but soon switched to a diesel engine. 1899 After a modified Holland VI passed the Navy trials, the company made a formal offer to sell the boat to the Navy and moved it down from New York to Washington, D.C. to enhance the PR effort with some demonstrations for members of Congress. Meanwhile, Simon Lake's Argonaut I was enlarged, improved, and redesignated Argonaut II. Continue: 1900-1918 Tour U-869 | Sole Survivor | Hazards of Diving Deep 400 Years of Subs | Map of Lost U-Boats | Fire a Torpedo Resources | Transcript | Site Map | Hitler's Lost Sub Home Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule About NOVA | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Jobs | Search | To print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated November 2000 |