|

|

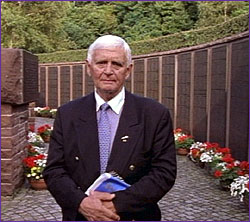

When a shorter version of the NOVA program "Hitler's Lost Sub" aired in Germany in April 1999, a remarkable thing happened. A 78-year-old man came forth and announced that he was the sole survivor of U-869. It turns out that Herbert Guschewski, one of two radio operators aboard the sub, had been taken off the U-boat with pleurisy just before it set sail on its final voyage. In June 1999, NOVA producer Rush DeNooyer interviewed Guschewski at a monument to the U-boat service in the northern German coastal town of Möltenort. Below is Guschewski's emotional response to the film and to the wrenching memories it resurrected of his lost comrades and his life aboard U-869 more than a half century ago. NOVA: What did you feel upon seeing the film about U-869? Guschewski: I must say that I can't bear to see it anymore. I am so agitated inside that I can hardly stand it. I had a vision of the bones of my body lying right there, if I hadn't been lucky enough to miss that voyage on U-869. I was able to live another 55 years, and I thank the Lord for that. NOVA: Why did you go into the submarine corps?

NOVA: Did you have an idol? Guschewski: Prien's attack at Scapa Flow was the initial reason I joined the submarine forces. [In October 1939, in the most famous U-boat patrol of the war, Lieutenant Commander Günther Prien snuck his U-47 into Scapa Flow, Britain's chief fleet anchorage, and sank the British battleship HMS Royal Oak. See Map of Lost U-boats.] That attack was highly glorified in the press back then. NOVA: Did you feel part of an elite as a U-boat officer? Guschewski: Without a doubt. You had to be totally healthy, no illnesses, not even a filled tooth. Before each mission we were checked several times. Yes, we were an elite, I have to say. NOVA: How did that feeling of eliteness manifest itself? Guschewski: The more ships sunk, the greater the admiration of the sailors and other officers became. If a boat sunk a lot of ships, it was celebrated accordingly back in the harbor and in the press. NOVA: And that was incentive enough?

NOVA: What was your job aboard U-869? Guschewski: There were two sergeants aboard. One was the Radio Operator Martin Horenburg; the other was me. [A wood-handled knife found with Horenburg's surname carved into it was the first clue as to the identity of U-869.] The two of us had three wireless operators beneath us. We had to operate the transceiver. We had to be ready to launch at all times, ready to contact the flotillas that sent us our orders. When we launched, the first thing was to fire the torpedo. The radio operators had to follow up via radio location and see whether the torpedo was a hit or a miss. And then we always had to be ready to send out radio messages, in case of an emergency on board. NOVA: Were you familiar with the equipment?

NOVA: With the good times of the submarines pretty much over, what was the morale of the crew at the time? Guschewski: The boat was put into service in the beginning of 1944. Nobody talked about the fears that they may have had. Maybe they just didn't want to say it, but they were frightened. I can only speak for myself. I did know how many boats and commanders didn't return. It was a known fact, because of well-aimed attacks by Allied aircraft at night, that the Allies must have invented new location machines and that we didn't have any real resistance to them yet. So there was fear, and more so than before. Especially us as the radio operators. We were located by Allied aircraft day and night—the beeping in the headsets, it went right through me. [Guschewski operated the radar search-receiver, which detected the 'beeping' of radar waves emanating from Allied aircraft as they homed in on the U-boat.] So the radio operators were especially in fear. Towards the end, in fact, the order to submerge didn't come from the commander anymore but from the radio operator, who said "We've got Volume 5" [refers to sound intensity of detected radar signal] and the boat went under. The next moment the bombs fell. So the crew had to completely rely on the radio operator—when I served in the Mediterranean it was me—otherwise we would have never returned and all been dead. Continue: Establishing identity Tour U-869 | Sole Survivor | Hazards of Diving Deep 400 Years of Subs | Map of Lost U-Boats | Fire a Torpedo Resources | Transcript | Site Map | Hitler's Lost Sub Home Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule About NOVA | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Jobs | Search | To print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated November 2000 |