|

|

|

|

Dr. Paul Groot

Dr. Paul Groot

|

One Astronomer's Universe

What's it like to think cosmological thoughts all day? How does one get one's

mind around such stupefyingly complex concepts as black holes or billions of

light-years? Where do the greatest satisfactions lie for one in this field?

Interviewed in his office at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics,

Dutch astronomer Paul Groot offers his reasons for pondering the

imponderable.

NOVA: How did you get into studying gamma-ray bursts?

Groot: It was basically by coincidence. I was doing my Ph.D., and my office

mate and friend, Titus Galama, was studying gamma-ray bursts using radio

telescopes. Right at the time he was doing this research, and I was there as

well, the positions in the sky of gamma-ray bursts became so accurate that we

could go after them with optical telescopes. At one point Titus and his

supervisor came to me and said, "You're familiar with optical telescopes, how

they work and how to analyze data from them. Can you help us out? We have a

long-standing problem, and you might contribute something to it." I said

sure.

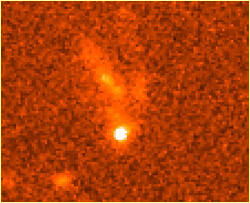

Shot by the Hubble, this image shows

the optical counterpart of one of the most powerful cosmic explosions ever

recorded—the gamma-ray burst of January 23, 1999. At its peak, the burst was

briefly visible with a pair of binoculars.

Shot by the Hubble, this image shows

the optical counterpart of one of the most powerful cosmic explosions ever

recorded—the gamma-ray burst of January 23, 1999. At its peak, the burst was

briefly visible with a pair of binoculars.

|

|

NOVA: And that decision resulted in the most thrilling moment of your career so

far, right?

Groot: Yes, as the NOVA program describes, it was the moment we found the

first-ever visual evidence of a gamma-ray burst. We were trying to see if we

could detect the afterglow of one, but since it was the first time we'd done

this kind of work, we didn't know if anything would be in those images. I had

taken one picture shortly after the gamma-ray burst and another one more like a

week later, and I was analyzing them.

I remember the moment I saw this one source that was bright in the first

picture and was gone in the next. This was a pretty big field in the sky, and

there was this one source that completely disappeared. Titus and I were looking

at it together, and we both said, "That's it." That was very exciting, because

we knew we were helping to solve a puzzle that had been around for 30

years.

|

"We knew we were helping to solve a puzzle that had been

around for 30 years."

|

NOVA: What's it like to work at the frontiers of science? I mean, everything

must be somewhat confused and jumbled, with new theories coming and going all

the time. Do you find that frustrating or stimulating?

Groot: Oh, stimulating, absolutely. We're out there at the edge, and we don't

know what's out there—nobody knows. The fun of it is trying to get a better

picture of how things are out in the universe—how they work, how they

started, how they evolve, and how they will end, things like that. It

constantly challenges you to make a contribution towards furthering our

knowledge of how the universe works. I think I would find it boring if we

already knew everything that was out there, and we were just rediscovering

things or looking at the same things but from a slightly different angle or

whatever.

NOVA: So what's the big issue in astronomy right now?

Groot: Well, there are a couple of big issues. One of them is how the universe

will end, which is very tightly linked to what the universe is made of. We know

that the matter that we see in optical light or in any other kind of radiation

only constitutes a small fraction of all the mass in the universe. That is,

what we see is only like 5 or 10 percent of what's out there.

It is astonishing to think, says Groot, that perhaps 95

percent of the universe is made up of matter that we can't see but we know is

there.

It is astonishing to think, says Groot, that perhaps 95

percent of the universe is made up of matter that we can't see but we know is

there.

|

|

There must be something else that is dark, which we call dark matter. We can't

see it, but we can see its effect on the light matter. There is influence

between the two through gravity, but we don't know what the dark matter is. I

find that astonishing, because we're so used to all the things around us, yet

we know that perhaps 95 percent of the universe is made of something completely

different. So that's one of the biggest issues in astronomy at the moment—the nature of dark matter. If we solve that, then we will be opening a

completely new window onto the universe.

NOVA: What about in the study of gamma-ray bursts? What's the next big

discovery to be made?

Groot: I think the next question that needs to be answered is, What is the

nature of gamma-ray bursts? What causes the explosions? We know now, through

the work we've been doing over the last few years, that they are at

cosmological distances of a billion light-years or more. But we still don't

know what is exploding. There are all kinds of indirect evidences for what is

going on, but there's nothing that really points to any one of several

scenarios that astronomers have proposed.

The amount of energy involved in these gamma-ray bursts is so large that we

have to come up with something exotic. There must be something strange, which

is not common in our own galaxy, that must be exploding. Again, that gives you

a new window onto extreme circumstances in the universe. It's an opportunity to

study some new kinds of physics, and that's very interesting.

|

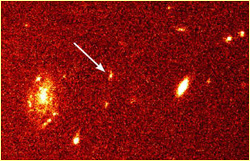

An estimated 12 billion light-years away, the galaxy

indicated in this Hubble image is thought to be the source of a huge gamma-ray

burst that was recorded on December 14th, 1997. Some estimates hold

that the burst released the energy of several hundred supernovae within a few

seconds.

An estimated 12 billion light-years away, the galaxy

indicated in this Hubble image is thought to be the source of a huge gamma-ray

burst that was recorded on December 14th, 1997. Some estimates hold

that the burst released the energy of several hundred supernovae within a few

seconds.

|

NOVA: The film mentions a theory that if a gamma-ray burst occurred in our

galactic neighborhood, life on Earth would essentially end, except for those

lucky creatures that live deep within the ground or oceans. Could this

happen?

Groot: I guess it could happen, but it has to happen very, very close by. I'd

say it would have to be within 100 light-years if it is really to affect the

Earth so drastically. And we have to ask the question, What causes gamma-ray

bursts? That's still an unsolved puzzle, and it now looks that at least a

certain class of gamma-ray bursts are caused by very, very massive stars

exploding. If such a star were present within 100 light-years, we would know

it, because it would be the brightest star in the sky. And we've seen no such

thing. So if that's the cause of gamma-ray bursts, I think that the Earth is in

no danger.

NOVA: That's a relief.

Groot: Well, there is another theory which says that gamma-ray bursts might be

caused by two neutron stars—very small, very compact stars—circling

around each other, and at one point they bump into each other. If that's the

case, it is possible that a binary neutron star system like that is present

within 100 parsecs of Earth. [A parsec is 3.26 light-years.]

"My

own personal feeling is that we're not alone."

|

|

If such stars do merge, there's nothing we can do about it until the moment it

happens. We could only say, "Hey, something went off, and it's very close by."

But I think chances of that are very small. If it happens somewhere else in our

galaxy, it will certainly affect us, though I don't think it will affect us to

the extent that life will be wiped out. [For more on this subject, see A Bad

Day in the Milky Way.]

NOVA: Speaking of life, how do you feel about the possibilities for life

elsewhere, and would most astronomers agree with you?

Groot: My own personal feeling is that we're not alone—life exists somewhere

besides Earth. I think most astronomers would agree with me there.

Why? Well, if you look at our sun, you realize how common a star it is. There's

nothing special about it, except for the fact, of course, that it's very close

by, and we're circling around it. And we now know that extrasolar planets

exist, with more and more being found all the time. I think the total count is

now up to 80 or so, and it's just a matter of time before more are identified.

The ones they've found so far are giant gas planets like Jupiter or Saturn, but

someday we'll be able to find Earth-like planets out there, and some of them

will orbit in the right range around their star for life to potentially

exist.

|

Planets beyond our solar system that

astronomers have discovered so far resemble giant gas planets like

Jupiter.

Planets beyond our solar system that

astronomers have discovered so far resemble giant gas planets like

Jupiter.

|

Now, the question is, Where is it? In what form? And will we ever find it or

get in contact with it?

NOVA: People say we're in the golden age of astronomy. Do you agree?

Groot: Absolutely. It could become even more golden, but if you compare to,

say, 50 years ago, the opening up of different parts of the electromagnetic

spectrum has been very, very important in developing astronomy in the last few

decades. [For a self-guided tour of the electromagnetic spectrum, see

Tour the

Spectrum.] We used to be able to see only optical light using normal,

ground-based telescopes. Then radio telescopes became available, allowing us to

look at the universe in radio waves. After that it was X-rays and submillimeter

and infrared. Now basically the whole electromagnetic spectrum has begun to

open up. Soon we may even be able to work with gravitational waves, which would

be completely different from anything that we do at the moment.

There's such a wealth of information coming from those advancements, coupled

with the technical development of detectors, which make it possible to use the

same-sized telescope but with a different detector and thus be much more

sensitive to things that are farther away or faint.

"We see all

these fascinating things, but we have no idea what's going on."

|

|

NOVA: To what extent does the field advance by new technologies versus new

ideas?

Groot: I think it's an interplay between the two. Certainly new technologies

are very, very important. You often see that breakthroughs are driven by the

availability of a new detector or a new satellite, or somebody who builds an

instrument that is able to look in a different part of the electromagnetic

spectrum. But new technology has to be combined with new ideas. Otherwise you

find yourself saying, "Okay, we see all these fascinating things, but we have

no idea what's going on."

Continue: Can amateur astronomers still make contributions to astronomy?

Photo credits

One Astronomer's Universe |

A Bad Day in the Milky Way

Catalogue of the Cosmos |

Tour the Spectrum

Resources |

Transcript |

Site Map |

Death Star Home

Search |

Site Map |

Previously Featured |

Schedule |

Feedback |

Teachers |

Shop

Join Us/E-Mail |

About NOVA |

Editor's Picks |

Watch NOVAs online |

To print

PBS Online |

NOVA Online |

WGBH

© | Updated January 2002

|

|

|

|