|

|

|

|

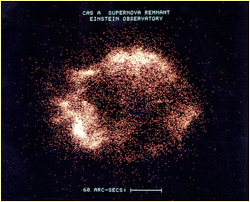

X-ray

photograph of the remnant of Supernova Cassiopeia A taken by the Einstein

Observatory.

X-ray

photograph of the remnant of Supernova Cassiopeia A taken by the Einstein

Observatory.

|

One Astronomer's Universe

Part 2 | Back to Part 1

NOVA: So, in this golden age, can amateur astronomers still make contributions

to astronomy?

Groot: Yes, absolutely. No doubt there. For one thing, when we professional

astronomers go observing, we apply for time on a telescope, and inevitably

there are too many people, so cuts have to be made. We end up being able to use

the telescope for only a very limited number of nights, say four or five, a

week perhaps, two weeks if we're very lucky. That means we can only study

stars, for instance, for that short period, and what happens after that and in

the long-term remains unknown.

Amateur astronomers have the luxury of having a telescope all to themselves,

because it's in the backyard, and they can observe whenever they want. It's

through amateur observers that we often find, for instance, new stars. People

look at a patch of sky, and all of a sudden there's a new star appearing there,

which is a star that was already there but it has suddenly become much

brighter. A lot of the work of discovering supernovae is actually done by amateur astronomers.

NOVA: It sounds like collaboration, or openness, comes naturally to

astronomers. But isn't there fierce competition as well, in which people sort

of horde their data until they get the right place to publish it, say?

Groot: It's a bit of both, I would say, but I think the openness prevails.

Astronomers in general are quite relaxed and quite open about their

observations. As an observer, often you're the only one looking at a particular

patch of sky, so it's very hard for other astronomers to steal your results.

Hoarding does happen sometimes; people do keep data to themselves. But I think

in general it's quite relaxed, and I like that.

"Doing science is

partly coming up with wild ideas once in a while."

|

|

NOVA: When somebody else presents an idea that you think is really out there,

do you ever find yourself saying, "Oh, come on?"

Groot: Oh, yeah. I mean, doing science is partly coming up with wild ideas once

in a while. Sometimes you read papers or go to a talk where somebody presents

his or her ideas, and you think, "Ah, that's just too fantastic to be true."

Your gut feeling tells you something can't be right. Maybe you don't know

exactly what it is from the start, but something in there doesn't feel right.

But you can be fooled. I've heard things that I thought, "No, that can't be

true," and later on it turned out to be true. So it works both ways.

NOVA: So as an astronomer, how do you get your brain around such mind-bending

concepts as wormholes or spacetime or even light-years?

Groot: Well, basically you have to get used to it. I don't think it is very

good to think about those things too deeply all the time, because that might

literally drive you mad. You treat it in an abstract way. For example, you

might say "This source is nine billion light-years away." But when you say

that, you're not thinking, "Okay, this is nine billion times so many miles, and

the circumference of the Earth is 26,000 miles, so it's so many circumferences

of the Earth away," because that doesn't say anything.

|

One can perhaps imagine the distance light travels in a year, but to scale

that up to a billion years, says Groot, "that becomes hard."

One can perhaps imagine the distance light travels in a year, but to scale

that up to a billion years, says Groot, "that becomes hard."

|

These numbers are so large that it's very hard to express them in human terms,

so to speak. A light-year—the distance light travels in a year—is still

something that you can understand. The time it takes light to travel from the

sun to the Earth is eight minutes. You can scale that up, and that's still

doable up to a year. But then to go to a billion years, that becomes

hard.

NOVA: So what makes a good astronomer?

Groot: Keeping an open mind, and being on the lookout for things that you don't

expect. For instance, say you're analyzing data that comes in from observations

you're doing, and you see something strange, something out of the ordinary. You

should have the openness of mind to say, "Hey, that's interesting, that doesn't

fit into the picture. What's going on?" Then you can go after it and adjust

your ideas about how stars work or how galaxies work, because there's some new

information.

That's not just for astronomers; that's for all scientists. But in astronomy it

happens a lot, because we can't predict the universe. We can't predict what's

going to happen tomorrow.

"Many astronomers have no idea how

telescopes actually work."

|

|

NOVA: Do you have to be a techno-wizard?

Groot: Absolutely not. I know many astronomers who are not techno-wizards. Even

among astronomers who use telescopes, many have no idea how telescopes actually

work. They know how to get the observations they want, but if the telescope

breaks and you ask them to fix it, they have no clue where to begin.

NOVA: What about math? Do you have to have an affinity for it?

Groot: Well, yeah. They always say math is the language of physics (and

astronomy is part of physics—it's astrophysics). So you should have a

certain affinity for math, but you don't have to be a superstar. I myself am

not a superstar in math. I mean, the lowest grade I had in my high-school exams

was in math.

|

Astronomers-in-the-making should follow their interests, Groot advises, not the latest

trends or fashions.

Astronomers-in-the-making should follow their interests, Groot advises, not the latest

trends or fashions.

|

NOVA: Do you have a single piece of advice that you'd put at the top of a list

for budding astronomers?

Groot: Go after the things that you like, that you think are fun. If you want

to be an astronomer or any kind of scientist, the reason why you do it should

be because it's fun and you like it. You should always try to follow that path.

If you like stars, go and study stars; if you like galaxies, go and study

galaxies. If you like to do theory, go and do theory. I think that's far more

important than following trends or fashions in astronomy or in physics or in

any research. That and having an inquisitive mind, wanting to know how things

work.

NOVA: I've heard, though, that in astronomy graduate school is hell, the

competition for the few jobs out there is mercenary, and once you get a job

you're poorly paid, you're at the mercy of your equipment, and you must publish

or perish. You spend a lot of time traveling to remote mountaintops, where you

stay all night for days on end—that is, if bad weather doesn't delay your

project for months. Does this jibe with your experience, and, if so, why would

anybody willingly become an astronomer?

"Somewhere deep inside I

have this urge to know what's out there."

|

|

Groot: Well, it's all true! The reason I still want to be an astronomer is

because I think it's fun. Somewhere deep inside I have this urge to know what's

out there and how it works and what our place in the universe is and how the

universe started and how it will end—all these questions. As long as you

like what you're doing, it outweighs all the other things you just mentioned.

The thing I like about astronomy over, say, physics is the fact that you can't

choose what's going to happen next. If you work in a physics lab, you can

adjust the temperature or the pressure or whatever quantity you're trying to

measure. But in astronomy you can't do that. You're at the mercy of what comes

from the universe towards us.

So you need to sit on that lonely mountaintop in the middle of nowhere—which, I have to say, can be in a very nice place as well. I mean, Hawaii's not

the worst place to go; the Canary Islands are not the worst place to go. It's

not all gloom and darkness out there. But something completely unexpected may

happen right at the moment when you're observing, and that makes it exciting.

It's the thrill of making new discoveries.

|

One of the joys of observing, Groot says, is that something

utterly unexpected could occur at the very moment you're using the

telescope.

One of the joys of observing, Groot says, is that something

utterly unexpected could occur at the very moment you're using the

telescope.

|

I'm an observer myself, so I often go to those mountaintops and sit there from

night to night. And one of the nicest things is when the data come in and you

get your first chance to shed light on what you've recorded. You say, "Okay,

what's in there? Is it what I expect, or is it different?" That stays exciting

no matter how often you go to a telescope to observe.

NOVA: When you're not on a mountaintop, what's your average day like?

Groot: It sounds very boring, but I have to go into the office and work from

nine to five. I have to reduce the data that I've collected from the telescope.

That is, I get something I can use from the raw format that came from the

telescope. Then I analyze that data. It's a lot of computer work, because

nowadays all major telescopes are equipped with electronic devices like video

cameras that capture the images or the spectra or whatever you get from the

telescope. It's all stored on hard disks and little tapes that you take with

you.

After you do the reduction and analysis and hopefully find something, you write

a paper to be published in a scientific journal. As part of that you have to go

through the literature, and you have to talk a lot with colleagues about

strange things that might happen and things you don't understand. It's very

much like being in an office.

"If you write 100 papers a year but

they're all crap, you won't make it."

|

|

NOVA: And must you publish or perish?

Groot: Yes and no. It's very important to publish, which is an inherent problem

in science nowadays, because sometimes it does feel like publish or perish. But

the quality of the papers is also very important. If you write 100 papers a

year but they're all crap, you won't make it. If you write only three or five

papers a year, but they're of very good quality and high impact, then you will.

Luckily, quality still wins out.

NOVA: So what's the difference between astronomers and astrophysicists, and do

they get along?

Groot: There's basically no difference between the two. Astronomy is the

old term, which literally means naming the stars, and astrophysics is

trying to understand the physics of the stars. Nowadays, they're the same, so

yes, I think astronomers and astrophysicists get along very well, because

they're the same people. And I generally get along very well with

myself.

NOVA: Can you sum up the life of an astronomer in five words or less?

Groot: "Fun." That's less than five words, I think! "International" would be a

very good one as well, because astronomy's a very international science, so you

have a lot of contact with people abroad, and you travel a lot. "Beautiful," in

that the observatories I go to are often in very remote places, and I always

find those places beautiful, even though they're usually in the middle of the

desert, and it's completely dry, and nothing grows there.

|

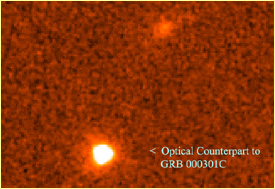

Recorded by the Hubble Space Telescope on March 1,

2000, this image shows the optical counterpart of a gamma-ray burst that

occurred on the far side of the visible universe.

Recorded by the Hubble Space Telescope on March 1,

2000, this image shows the optical counterpart of a gamma-ray burst that

occurred on the far side of the visible universe.

|

NOVA: You have two words left.

Groot: "Opportunity," I would say. Opportunities arise very quickly in

astronomy, because things can happen all of a sudden, like the work I did with

gamma-ray bursts. One week I was doing my own science, which is not really in

the limelight, and the next week I discovered, with Titus Galama, the first

optical counterpart of a gamma-ray burst. The whole astronomy world fell over

us, because that's what they've been aiming for for 30 years. It is still one of

the hottest topics in astronomy even now, five years later.

That's four. The fifth one.... Well, "fun" again, if that's allowed, to put fun

in twice.

Interview conducted by Peter Tyson, editor in chief of NOVA Online

Photo credits

One Astronomer's Universe |

A Bad Day in the Milky Way

Catalogue of the Cosmos |

Tour the Spectrum

Resources |

Transcript |

Site Map |

Death Star Home

Search |

Site Map |

Previously Featured |

Schedule |

Feedback |

Teachers |

Shop

Join Us/E-Mail |

About NOVA |

Editor's Picks |

Watch NOVAs online |

To print

PBS Online |

NOVA Online |

WGBH

© | Updated January 2002

|

|

|

|