|

|

|

|

|

With all the heat they've taken for promoting

smoking, cigarette manufacturers have spent fortunes

trying to develop a "safer" cigarette.

With all the heat they've taken for promoting

smoking, cigarette manufacturers have spent fortunes

trying to develop a "safer" cigarette.

|

"Safer" Cigarettes: A History

by Tara Parker-Pope

Although the cigarette industry has spent much of the past

50 years denying a link between smoking and disease, the

industry has also dedicated a significant amount of time and

money to develop a "safe" cigarette. A safe cigarette that

can both satisfy smokers' demands for taste and nicotine

delivery and placate public health concerns is the Holy

Grail of the tobacco industry. The company that comes up

with it first likely could dominate the entire industry by

selling the newfangled smoke at a significant premium and

grabbing market share from its competitors. Indeed, in the

1950s, Philip Morris researchers already saw the potential

of a "healthy" cigarette and had even begun to suggest that

the company could capitalize on health concerns by admitting

that cigarettes were harmful. "Evidence is building up that

heavy smoking contributes to lung cancer," wrote a Philip

Morris scientist in July 1958. He then suggested that the

company have the "intestinal fortitude to jump to the other

side of the fence," and that the company would have a

"wealth of ammunition" to attack competitors who did not

have safer cigarettes.

But several factors have stood in the way of the development

of a safer smoke. Taking the toxins out of cigarette smoke

has turned out to be a technological challenge. The biggest

problem has been maintaining the taste and smoking

sensations that smokers crave—so far, no company has

overcome those obstacles. And industry lawyers have balked

at the suggestions that cigarette makers embark on research

to make safe cigarettes out of fears of the tricky legal

problem such research would create for the entire industry.

Patrick Sheehy, the former chief executive of British

American Tobacco, wrote in 1986 that safe cigarette research

would be tacit admission that cigarettes are dangerous. "In

attempting to develop a "safe" cigarette you are, by

implication, in danger of being interpreted as accepting the

current product is unsafe, and this is not a position that I

think we should take," he wrote.

Among cigarette manufacturers, finding a way to

remove toxins from cigarette smoke is, well, a burning

desire.

Among cigarette manufacturers, finding a way to

remove toxins from cigarette smoke is, well, a burning

desire.

|

|

Finally, the safe cigarette has been stymied by the very

groups who are most concerned about the health effects of

smoking: antitobacco groups and public health officials. The

cigarette industry's efforts to market safer cigarettes have

been met with fierce opposition by antitobacco activists,

who want to see such products labeled as nicotine delivery

devices and subjected to government regulations. Although

the opposition of health groups to a safe cigarette would

seem contradictory, it is borne out of a deep mistrust of

the cigarette companies, whose strategy of denial over the

years has created a credibility gap with the public health

community.

The "tar derby"

The cigarette makers first began making noises about safer

cigarettes in the 1950s during a period now known among

historians as the "tar derby." As a result of growing public

concerns about smoking and health, the cigarette makers

responded with a variety of new filter cigarettes that would

ostensibly reduce tar levels. But the rise of the filter

cigarette was more a marketing ploy than anything else.

There was little evidence to suggest that filter cigarettes

were any healthier than regular cigarettes, and the tobacco

companies' own researchers knew this to be the case. A 1976

memo from Ernest Pepples, Brown & Williamson's vice

president and general counsel, noted that filter cigarettes

surged from less than 1 percent of the market in 1950 to 87

percent in 1975. "In most cases, however, the smoker of a

filter cigarette was getting as much or more nicotine and

tar as he would have gotten from a regular cigarette. He had

abandoned the regular cigarette, however, on the ground of

reduced risk to health," wrote Pepples.

|

One of the competitors in the "tar derby."

One of the competitors in the "tar derby."

|

Even today, many smokers think that low-tar or so-called

light or ultra-light cigarettes are better for them than

full-strength smokes. Because reducing tar levels also tends

to lower nicotine levels, studies have shown that smokers

inadvertently compensate for the loss of the nicotine.

Smokers of low-tar cigarettes inhale more deeply, take puffs

more often, and even cover up the tiny holes near the filter

that were put there to reduce the amount of smoke, and

subsequently the amount of tar, that a smoker inhales. (To

take a closer look at ventilation holes and other design

elements in today's cigarettes, see

Anatomy of a Cigarette.)

Toward "safer" smokes

During the 1960s cigarette makers embarked on extensive

research to create a safe cigarette. The goal was to remove

the toxins from a conventional cigarette without altering

the taste or smoking experience. Memos from that time period

show that some tobacco company executives were genuinely

interested not only in profits but in making their products

healthier. In 1962, Charles Ellis, a British American

Tobacco research executive, noted that painting mice with

"fresh" smoke condensate, more similar to the "fresh" smoke

inhaled by smokers, might prove to be more harmful than the

older, stored condensate often used in such experiments.

"This possibility need not dismay us, indeed it would mean

that there really was a chemical culprit somewhere in smoke,

and one, moreover, that underwent a reaction fairly quickly

to something else. I feel confident that in this case we

could identify this group of substances, and it would be

worth almost any effort, by preliminary treatment,

additives, or filtration, to get rid of it."

Industry documents show that tobacco companies focused their

safe-cigarette research on several areas, including the

development of synthetic tobacco, boosting nicotine levels

in low-tar cigarettes (so smokers wouldn't have to

compensate for a loss of nicotine), and selective filtration

of the most toxic substances in cigarette smoke, such as

carbon monoxide. Research into safe cigarettes also has

focused on the removal or lowering of four types of

carcinogenic compounds: nitrosamines, widely viewed as the

most deadly cancer-causing agents in tobacco smoke;

aldehydes, formed by the burning of sugars and cellulose in

tobacco; polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH's), which

form in the cigarette behind the burning tip; and traces of

heavy metals present in tobacco as a result of fertilizers

used on the plant.

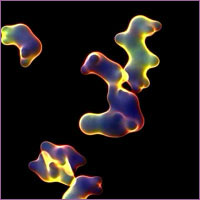

This animation shows how the heat from tobacco

combustion causes molecules to fragment into unstable

arrangements, which recombine to form carcinogenic

compounds of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, or

PAH's.

This animation shows how the heat from tobacco

combustion causes molecules to fragment into unstable

arrangements, which recombine to form carcinogenic

compounds of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, or

PAH's.

See the animation in:

QuickTime

|

RealVideo

Get video software:

QuickTime

|

RealVideo

|

|

But despite the industry's early optimism about simply

removing the toxic elements from a cigarette, the quest for

a safe cigarette proved to be a technically and politically

daunting challenge. Industry researchers often found ways of

lowering one or two of the dangerous compounds, only to

discover that their tinkering had either increased the level

of some other harmful compound or so dramatically altered

the cigarette that it wouldn't be accepted by consumers. In

1975, Brown & Williamson introduced a new cigarette,

Fact, which had been designed to selectively remove certain

compounds, including cyanide, from cigarette smoke. But the

product was pulled from the market after just two years.

Scientists also experimented with tobacco substitutes,

including ingredients made with wood pulp, that were said to

be less toxic than tobacco. But those products ran into a

new set of problems because they were no longer a naturally

occurring tobacco product but a synthetic creation about

which health claims were being made. That meant government

regulators viewed the tobacco substitutes more like drugs,

subjecting them to a regulatory morass that the cigarette

makers wanted to avoid. In 1977, a few British tobacco

companies, Imperial, Gallaher, and Rothmans, which could

avoid U.S. Food and Drug Administration scrutiny, launched

several versions of cigarettes made with tobacco

substitutes. But the products met with resistance from

health groups, who claimed the new cigarettes were still

unsafe, and the products floundered and were withdrawn after

just a few months.

Continue: The XA Project

|

|

Anatomy of a Cigarette

|

"Safer" Cigarettes: A History

|

The Dope on Nicotine

|

On Fire

Resources

|

Teacher's Guide

|

Transcript

|

Site Map

|

Search for a Safe Cigarette Home

Search |

Site Map

|

Previously Featured

|

Schedule

|

Feedback |

Teachers |

Shop

Join Us/E-Mail

| About NOVA |

Editor's Picks

|

Watch NOVAs online

|

To print

PBS Online |

NOVA Online |

WGBH

©

| Updated October 2001

|

|

|

|