|

|

|

|

"Safer" Cigarettes: A History

Part 2 |

Back to Part 1

|

The mouse that roared

The mouse that roared

|

The XA Project

In the 1970s, Liggett Group, Inc. embarked on its own

safe-cigarette program known as the "XA Project." The

project focused on blending additives to tobacco to

neutralize cancer-causing compounds. The company discovered

that blending certain catalysts with tobacco would destroy

PAH's—the dangerous compounds which form behind the

cigarette's burning tip. The problem was, the company had

demonstrated this in mouse skin painting tests—the

same type of test conducted by Ernest Wynder that the entire

tobacco industry had spent years debunking. Nonetheless,

skin painting tests related to the XA Project showed that

cancerous tumors were virtually eliminated when the catalyst

was added to tobacco.

Liggett faced a marketing problem if it pursued the XA

Project cigarettes. How could the company market the

benefits of the XA Project cigarettes without making health

claims that would subject it to government scrutiny? And how

could the company promote mouse skin tests as proof their

new cigarettes worked at the same time its lawyers were in

courtrooms challenging the validity of mouse tests while

defending the company against smokers' lawsuits? A former

industry lawyer now says that Liggett was pressured by other

cigarette makers to abandon the effort because the

"marketing and sale of a safe cigarette could result in

infinite liability in civil litigation as it would

constitute a direct or implied admission that all other

cigarettes were unsafe." Liggett eventually abandoned the

project.

By the early 1980s, other cigarette makers also had

abandoned many of their efforts to develop a safe cigarette.

In addition to the technological hurdles they faced,

industry lawyers had grown increasingly wary about the

research, and the concession, implicit in such research,

that existing cigarettes weren't safe. Nonetheless, more

than 150 patents related to designing safe cigarettes have

been filed in the United States and the United Kingdom

during the past 25 years. Tobacco executives say the fact

that a patent has been filed doesn't mean the product is

necessarily marketable or acceptable to consumers, but the

sheer volume of patents shows that the industry has invested

heavily in developing a safer cigarette even as its own

executives were denying any link between smoking and

disease. And there are now several claims from former

industry workers that many tobacco companies shelved

research into safer products out of fear of exposing

themselves to additional liability. In 1998, for instance, a

former Philip Morris researcher testified that the company

shelved promising research to remove cadmium, a lung

irritant, from tobacco plants.

Smokers didn't give Premier a chance, its maker

maintains.

Smokers didn't give Premier a chance, its maker

maintains.

|

|

High-tech cigarettes

Despite such criticism, the major cigarette makers have

attempted to market several versions of safer cigarettes. In

1988, RJR introduced a high-tech cigarette called Premier.

Premier, touted as a virtually smokeless cigarette that

dramatically reduced the cancer-causing compounds inhaled by

smokers, was made of aluminum capsules that contained

tobacco pellets. The pellets were heated instead of burned,

thereby producing less smoke and ash than traditional

cigarettes. Although the product looked like a traditional

cigarette, it required its own instruction booklet showing

consumers how to light it.

From the beginning, Premier had several strikes against it.

RJR had spent an estimated $800 million developing the

brand, and the total cost was expected to soar to $1 billion

by the time it was placed in national distribution. The

costly project was put into test market just as Kohlberg

Kravis Roberts & Co. had embarked on a $25 billion

leveraged buyout of RJR that had saddled the company with

debt. And the cigarette faced a lengthy regulatory battle

after public health officials argued it should be regulated

by the FDA as a drug. But the biggest problem with Premier

was the fact that consumers simply couldn't get used to it.

Many smokers complained about the taste, which some smokers

said left a charcoal taste in their mouths. RJR had also

gambled that smokers would be willing to give Premier

several tries before making a final decision about whether

to smoke it. RLR estimated that to acquire a taste for

Premier, smokers would have to consume two to three packs to

be won over. But as it turned out, most smokers took one

cigarette and shared the rest of the pack with friends, and

few bothered to buy it again. RJR scrapped the brand in

early 1989, less than a year after it was introduced.

In 1989, Philip Morris entered the fray with a virtually

nicotine-free cigarette called Next that it claimed was

better than other low-nicotine varieties because its taste

was indistinguishable from regular cigarettes. The nicotine

was removed from Next using high-pressure carbon dioxide in

a process similar to the method used by coffee companies

when making decaffeinated coffee. Next cigarettes were

touted for their "rich flavor" and referred to as "de-nic"

cigarettes. But tobacco critics complained that Next

actually had higher tar levels than many cigarettes, and

that heavy smokers would simply smoke more Next cigarettes

to give their bodies the nicotine they crave. (To learn how

the brain becomes dependent on nicotine, see

The Dope on Nicotine.) The product flopped and was withdrawn.

|

In RJR's Eclipse, most of the tobacco doesn't burn

but rather heats up, producing a smoke-like vapor.

In RJR's Eclipse, most of the tobacco doesn't burn

but rather heats up, producing a smoke-like vapor.

|

Despite those setbacks, both RJR and Philip Morris have

tried again with high-tech versions of smokeless cigarettes.

In 1994, RJR began testing the Eclipse smokeless cigarette,

which claimed to reduce secondhand smoke by 85 to 90

percent. Eclipse is more like an ordinary cigarette than its

predecessor Premier because it contains tobacco and

reconstituted tobacco. But it also includes a charcoal tip

that, when lighted, heats glycerin added to the cigarette

but does not burn the tobacco. The result is a cigarette

that emits tobacco flavor without creating ash and smoke.

But RJR isn't touting Eclipse as a safe cigarette, instead

marketing it as a more socially acceptable product less

offensive to non-smokers. Indeed, because Eclipse still

burns some tobacco, it has tar levels similar to those of

ultra-light cigarettes already on the market. Eclipse emits

lower tar levels of cancer-causing compounds than many

existing cigarettes, but it still produces carbon monoxide

and nicotine. And questions have also been raised about the

effects of heating glycerin. When burned, glycerin is known

to be carcinogenic. It also remains unclear whether the FDA

will attempt to regulate Eclipse if RJR launches it

nationally.

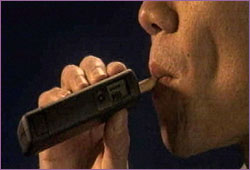

Philip Morris is testing its own high-tech cigarette called

Accord, which has been described as a cigarette encased in a

kazoo-shaped lighter. Consumers buy a $40 kit that includes

a battery charger, a puff-activated lighter that holds the

cigarette, and a carton of special cigarettes. To smoke the

cigarettes, a smoker sucks on the kazoolike box. A microchip

senses the puff and sends a burst of heat to the cigarette.

The process gives the smoker one drag and does not create

ashes or smoke. An illuminated display shows the number of

puffs remaining, and the batteries must be recharged after

every pack. It's unclear whether smokers will find the

low-smoke and -ash benefits desirable enough to justify

learning an entirely new smoking ritual. Although Philip

Morris doesn't make health claims about Accord, the company

in 1998 told the Society of Toxicology that Accord generated

83 percent fewer toxins than a regular cigarette.

For $40, the Accord smoker gets a battery charger,

heating device, and carton of special cigarettes.

For $40, the Accord smoker gets a battery charger,

heating device, and carton of special cigarettes.

|

|

Lowering nitrosamines

Perhaps the most promising new technology to make a safer

cigarette lies in research to lower nitrosamines, those

prevalent and deadly cancer-causing compounds in cigarettes.

Brown & Williamson and RJR are developing cigarettes

that use a special tobacco with lower nitrosamine content.

The tobacco is cured with a special process that inhibits

the formation of nitrosamines. But Brown &Williamson

isn't planning to tout the health benefits of the

nitrosamine-free smoke. "We can't be sure nitrosamine-free

tobacco is necessarily safer," a B&W spokeswoman told

the Wall Street Journal. "We don't want to claim the

product is safer unless we are sure it is. It's a bit of a

muggy area."

Although public health officials describe the quest for a

nitrosamine-free cigarette as a step in the right direction,

the research still raises concerns that smokers could be

lulled into a false sense of security. Cigarettes without

nitrosamines still produce other carcinogens, scientists

say, and more smokers die of heart-related ailments than

cancer. As Dietrich Hoffmann of the American Health

Foundation says, "The best cigarette is no cigarette."

Tara Parker-Pope, a reporter for the

Wall Street Journal, is the author of

Cigarettes: Anatomy of an Industry from Seed to

Smoke

(The New Press, 2001), from which this article was

excerpted with permission.

|

|

Anatomy of a Cigarette

|

"Safer" Cigarettes: A History

|

The Dope on Nicotine

|

On Fire

Resources

|

Teacher's Guide

|

Transcript

|

Site Map

|

Search for a Safe Cigarette Home

Search |

Site Map

|

Previously Featured

|

Schedule

|

Feedback |

Teachers |

Shop

Join Us/E-Mail

| About NOVA |

Editor's Picks

|

Watch NOVAs online

|

To print

PBS Online |

NOVA Online |

WGBH

©

| Updated October 2001

|

|

|

|