|

|

The Sky's Eyes:

Remote Sensing in Archaeology

Some would argue that the greatest advancement in archaeology since the shovel

is remote sensing, or being able to "see" an archaeological site without

actually excavating it. (If nothing else, it's certainly easier on the lower

back.)

This type of "seeing" can take place either from the air or the ground. Ground

Penetrating Radar (GPR), dubbed "the red sled" on the Ubar dig, is a radar

device that, when dragged over a site, can give a rough picture of any

structure that may lie beneath. Geophysical Diffraction Tomography (GDT)

accomplishes the same thing with sound waves coming from an 8-gauge shotgun.

But perhaps the most spectacular remote sensing tools are those that create

images of earth from the sky. This type of "seeing" can take place either from the air or the ground. Ground

Penetrating Radar (GPR), dubbed "the red sled" on the Ubar dig, is a radar

device that, when dragged over a site, can give a rough picture of any

structure that may lie beneath. Geophysical Diffraction Tomography (GDT)

accomplishes the same thing with sound waves coming from an 8-gauge shotgun.

But perhaps the most spectacular remote sensing tools are those that create

images of earth from the sky.

The first known aerial photographs of an archaeological site were taken from a

war balloon by Lieutenant P. H. Sharpe in the early 1900s. The target was

Stonehenge. In World War I, photographers conducting military reconnaissance

flights kept running across sites of archaeological interest. It wasn't long

before military officers began actively seeking out such sites on their own.

One pioneer was Lieutenant-Colonel G. A. Beazeley, who discovered the extensive

outlines of ancient canals in Mesopotamia's Tigris-Euphrates plain. But as

useful as aerial photographs are, they have their limitations: namely,

airplanes can fly only so high and human eyes can see only so much.

"Our eyeballs are tuned-up for finding lunch, not for differentiating rocks or

terrain," explains Ron Blom of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, NASA's center for

unmanned planetary exploration. "If our eyeballs could see the longer

wavelengths on the electromagnetic spectrum, what looks like a red soil to your

eye right now would actually turn out to be all sorts of beautiful colors.

There's a lot of information out there that our eyes just can't see."

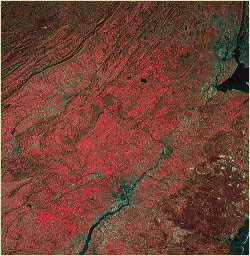

To solve that problem, scientists designed and launched the first

multi-spectral imaging satellite in 1972. Called Landsat-1, the satellite sent

back images of an earth no one had ever seen before. Reading visible light,

as well as the infrared bands of the electromagnetic spectrum, Landsat revealed

a psychedelic world of magenta vegetation, black water and gold forests. It

also showed pollution off the coast of New Jersey, unmapped lakes in Iran and

additional branches of the San Andreas fault. "Rocks, soils and vegetation

look different at these longer wavelengths," explains Bloom. "And because a

lot of materials appear more contrasty at longer wavelengths, they're easier to

isolate and detect." To solve that problem, scientists designed and launched the first

multi-spectral imaging satellite in 1972. Called Landsat-1, the satellite sent

back images of an earth no one had ever seen before. Reading visible light,

as well as the infrared bands of the electromagnetic spectrum, Landsat revealed

a psychedelic world of magenta vegetation, black water and gold forests. It

also showed pollution off the coast of New Jersey, unmapped lakes in Iran and

additional branches of the San Andreas fault. "Rocks, soils and vegetation

look different at these longer wavelengths," explains Bloom. "And because a

lot of materials appear more contrasty at longer wavelengths, they're easier to

isolate and detect."

Archaeologists didn't appreciate the full potential of space imaging until

1981, when NASA launched an imaging system called SIR-A on the Space Shuttle.

Unlike Landsat 1, which used reflected sunlight to make an image, SIR-A sent

out its own radar signal and then "listened" to the echo. Archeologist Farouk

El-Baz, now director of the Center for Remote Sensing at Boston University, had

asked NASA to fly SIR-A over the eastern Sahara desert, hoping it could make

sense of the anomalous rock formations he had been studying there. No one was

quite prepared for the images that came back.

The Sahara is the driest place on earth right now, but SIR-A was able to

penetrate the sand and reveal an ancient landscape below that, amazingly, had

been carved by running water. "The Sahara once looked like the landscape of

Europe," El-Baz reported, "with rivers, lakes, mountains and valleys." The

banks of the old rivers beds, dubbed "radar rivers" by researchers, turned out

to be excellent sites for archaeological excavation, yielding a bevy of

Paleolithic tools and artifacts.

(continued)

Lost City Home | Remote Sensing | Interview | Desert Finds

Artifact Gallery | Map | Links

|

|

|