|

|

|

When news of SIR-A's x-ray like abilities reached the news media, phones

started ringing off the hook at NASA's Jet Propulsion Lab. "We started getting

calls from people saying, 'I know where Atlantis is,' and, 'If you guys give me

the data, I'll find my Grandmother's buried treasure,' and so on," laughs Ron

Blom. "What people didn't realize was that the radar could only penetrate

about 10-15 feet and could only accomplish this through exceedingly dry and

fine-grained material—like desert sand." Even so, SIR-A demonstrated the

enormous power of space-borne imaging for archaeologists.

In recent years, the technology has only become more sophisticated. There are

now five Landsat satellites orbiting the earth (not to mention the numerous

imaging satellites belonging to other countries in orbit). Landsat 4 and

Landsat 5 are equipped with something called "Thematic Mapper," which can radio

seven channels of digital data back to earth—three in the visible spectrum,

three in the reflective infrared spectrum and one in the thermal infrared

spectrum.  This multi-spectral data, especially when enhanced by computer

processing, can detect the slightest variations in the earth's surface—like

the trail leading to the Ubar site. "The surface material of the incense trail

basically had fewer rocks, more sand, and more dust than the surrounding

desert," explains Ron Bloom. "That, maybe along with a couple thousand years of

camel dung, stood out extremely well at the longer wavelengths." This multi-spectral data, especially when enhanced by computer

processing, can detect the slightest variations in the earth's surface—like

the trail leading to the Ubar site. "The surface material of the incense trail

basically had fewer rocks, more sand, and more dust than the surrounding

desert," explains Ron Bloom. "That, maybe along with a couple thousand years of

camel dung, stood out extremely well at the longer wavelengths."

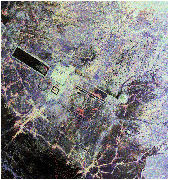

Radar imaging has also undergone a dramatic technological advance. SIR-A was a

single-band radar while SIR-C, which flew twice in 1994, is a multi-wavelength

radar. Its particular strength is detecting subtle differences in the earth's

topography and penetrating some surface materials, especially sand, leaves and

ice. One of SIR-C's recent targets was the ancient city of Angkor in Cambodia. The radar's longest wavelengths were able to partially penetrate the dense

jungle vegetation and pick up details of the topography hidden below. As a

result, researchers were able to identify water reservoirs and moats around the

temple complexes that hadn't been visible from the ground. Similarly, recent

radar images of the Great Wall of China found an earlier piece of the Wall—long suspected to have existed, but never located—buried under dirt and

sand.

The radar's longest wavelengths were able to partially penetrate the dense

jungle vegetation and pick up details of the topography hidden below. As a

result, researchers were able to identify water reservoirs and moats around the

temple complexes that hadn't been visible from the ground. Similarly, recent

radar images of the Great Wall of China found an earlier piece of the Wall—long suspected to have existed, but never located—buried under dirt and

sand.

Experts are quick to warn that remote sensing, though extremely useful in some

cases, is not a silver bullet. "The Ubar site was found by a combination of

historical research, remote sensing data and a lot of hard work by guys like

Juris Zarins," stresses Ron Bloom.

Zarins agrees with Blom, but is clearly a fan of the new technology. "Remote

sensing allows you to get a picture of the terrain you otherwise wouldn't see.

It gives you a better feel for what the terrain is like and where the

possibility of finding sites are. And when it's put together with GPS (Global

Positioning System) and you're able to tell an automobile driver or a

helicopter pilot, 'Go to this site at these coordinates,' and they can drop you

right off there, it's very very helpful."

Lost City Home | Remote Sensing | Interview | Desert Finds

Artifact Gallery | Map | Links

|

|

|