|

Public support plummeted and opinion turned against Mary Mallon in

1915 because of her conscious return to cooking when people believed

she should have learned her lesson. "The chance was given to her

five years ago to live in freedom," editorialized the

New York Tribune, and "she deliberately elected to throw it

away." Historians have since that time been no more lenient in their

assessment of Mallon's informed return to cooking. In 1994, Robert

J. T. Joy put it directly: "Consider that Mallon disappeared for

five years, and used several aliases and went straight back to

cooking! ... Now, as far as I am concerned, this verges on assault

with the possibility of second degree murder. Mallon knows she

carries typhoid, knows she should not cook—and does so."

To be sure, Mary Mallon was not entirely blameless when she

knowingly returned to cooking in 1915, but the blame must be more

broadly shared. Much of what Mallon did can be explained by events

greater than herself and beyond her control. It is only in the full

context of her life and the actions of the health officials and the

media that we can understand the personal position of Mary Mallon

and people like her—people whom society accuses of endangering

the health of others—and can hope to formulate policies that

will address their individual needs while still permitting

governments to do what they are obligated to do, act to protect the

public's health.

Mary's straits

Mary's straits

Mallon was not a free agent in 1914, when she returned to cooking.

Consider her circumstances. She had been abruptly, even violently,

wrenched from her life, a life in which she found various

satisfactions and from which she earned a decent living. She was

physically separated from all that was familiar to her and isolated

on an island. She was labeled a monster and a freak. [For more on

the quarantine of Mary Mallon, aka "Typhoid Mary," see

In Her Own Words.]

She was not permitted to work at a job that had sustained her, but

she was not retrained for any comparable work. If Ernst J. Lederle,

the New York City Health Commissioner who had released her in 1910,

helped her find a job in a laundry, it did not provide the wages or

job satisfaction to which she had previously become accustomed. Nor

did it provide the social amenities, as limited as they were, of

domestic work in the homes of New York's upper class. The health

department, for all of Lederle's words of obligation to help her in

1910, did not provide her with long-term gainful employment.

Neither did health officials, who precipitously locked Mallon up,

succeed in convincing Mallon that her danger to the health of people

for whom she cooked was real and lifelong. The medical arguments

that carried weight among the elite at the time and have become more

broadly convincing since did not resonate with her. There was no

welfare system to support her. There was no viable "safety net,"

practical or intellectual, for an unemployed middle-aged Irish

immigrant single woman.

Hard choices

Hard choices

So she did what many other healthy carriers since have done:

returned to work to support herself. And the health department

responded by doing what it felt it had to do when faced with a now

very public uncooperative typhoid carrier: returned her to

isolation. New York health officials did not isolate all the

recalcitrant carriers it identified; many who had disobeyed health

department guidelines were out in the streets during the years

Mallon remained on North Brother Island, the East River islet where

she was quarantined. But officials had reason to act as they did.

And so did Mary Mallon.

Health officials chose not to deal with their first identified

healthy carrier in a flexible way.

In other words, there were choices for both the health officials and

Mary Mallon, and judgment, when we make it, should take this full

context into account. Events could have evolved in a different

pattern. If tempers had not been raised to fever pitch in 1907, when

Mallon was first quarantined on North Brother Island, and

positions not solidified, various compromises and possibilities

would have been available for education, training, and employment, all of which might have led to decreasing the

potential of Mallon's typhoid transmission.

Health officials, who certainly held the reins of power most

tightly, chose not to deal with their first identified healthy

carrier in a flexible way. They chose to make an object lesson of

her case. But it was a choice. If they had shown some personal

respect for how difficult it was for Mary Mallon to cope with what

happened to her, it is conceivable that she would have responded in

kind and come to respect their position. As it happened, neither

side considered the other, and communication was stopped short.

Proper treatment

Proper treatment

How can we address the problem that is now, still, again,

before us? Shall we insist on locking up the people who are sick or

who are at risk of becoming sick because they threaten the health of

those around them? Our own situation in large part determines how we

think about these questions and informs our various responses to

this public health dilemma. We can view people who carry disease as

if they consciously bring sickness and death to others—like

the demon breaking skulls into the skillet, as a 1909 newspaper

illustration depicted Mary Mallon [see image at right above]. We can

view such people as inadvertent carriers of disease, as innocent

victims of something uncontrollable in their own bodies. We can see

disease carriers as instruments of others' evil, as victims of

society's or science's perversity.

Wherever we position ourselves, as individuals and as a society, we

must come to terms with the fundamental issue that whether we think

of them as guilty or innocent, people who seem healthy can indeed

carry disease and under some conditions may menace the health of

those around them. We can blame, fear, reject, sympathize, and

understand: withal, we must decide what to do. Optimally, we search

for responses that are humane to the sufferers and at the same time

protect those who are still healthy.

The conflict between competing priorities of civil liberties and

public health will not disappear, but we can work toward developing

public health guidelines that recognize and respect the situation

and point of view of individual sufferers. People who can endanger

the health of others would be more likely to cooperate with

officials trying to stem the spread of disease if their economic

security were maintained and if they could be convinced that health

policies would treat them fairly. Equitable policies applied with

the knowledge of history should produce very few captives to the

public's health.

|

|

Mary Mallon (wearing glasses) photographed with

bacteriologist Emma Sherman on North Brother Island in

1931 or 1932, over 15 years after she had been

quarantined there permanently.

|

|

|

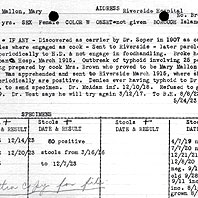

An old file card detailing results from tests on stool

specimens from Mary Mallon gives a capsule history of

her capture and quarantine.

|

|

|

Part of the New York American article of June 20,

1909, which first identified Mary Mallon as "Typhoid

Mary."

|

|

|