Investigating 9/11In 2002, the U.S. House and Senate Intelligence committees asked attorney Eleanor Hill to lead their investigation into why the intelligence community failed to foresee 9/11. Hill was a 20-year veteran of inquiries into government lapses and abuses, including Iran-Contra. Throughout the late 1990s, she also had served as Inspector General of the Department of Defense, a role that gave her insight into the workings of various intelligence agencies. As Staff Director of the Joint Congressional Inquiry on the September 11th Attacks, Hill oversaw the hearings and report that reviewed the nation's highly classified intelligence files and probed what our intelligence community knew regarding the terrorist threat prior to the attacks. James Bamford, coproducer and writer of NOVA's "The Spy Factory," spoke to Hill about the experience. RAISING QUESTIONSJames Bamford: Was the Joint Congressional Inquiry the first substantial look at what the intelligence community knew about 9/11? Eleanor Hill: It was. Before our work, the [intelligence] agencies had testified on the Hill. They basically said that they did everything that could have been done. And the position of the [Bush] administration at the time was that they didn't need a commission, because there was no evidence that anything had gone wrong. The [House and Senate] Intelligence committees took it upon themselves, with agreement from the White House, that they would investigate what the intelligence community knew, or should have known, before the attacks. That's what we did. Q: Were the various agencies—CIA, NSA, DIA [Defense Intelligence Agency]—cooperative? Hill: They all certainly told us they would cooperate. But as with most investigations, the more we dug around and began to come up with things that had not gone right, there was resistance. Our report goes into some issues where we argued vehemently, and I personally spent about seven months debating with the intelligence community, trying to get as much of our report declassified as possible. What they do is secret. Much of the information is very sensitive, classified. So they are not used to a lot of aggressive oversight, particularly public oversight. The culture of secrecy makes them resistant, or at least cautious, and that made the investigation more difficult. MISSED OPPORTUNITIESQ: In your report, you note that the NSA picked up intelligence on three of the 9/11 hijackers in 1999. Can you broadly describe this? Hill: Several times in 1999, the NSA analyzed communications that involved individuals who, after 9/11, we came to find out were hijackers. They analyzed communications involving an individual named "Khaled," who turned out to be Khalid al-Mihdhar; Nawaf, who turned out to be Nawaf al-Hazmi; and finally, I think in late 1999, they had the name Salem, who was Salem al-Hazmi. The NSA knew that those individuals were connected with a suspected terrorist facility in the Middle East—one tied to Al Qaeda efforts against U.S. interests. So that's pretty significant information. Unfortunately, at least in the beginning, the significance was not recognized. It was not immediately passed on to other members of the intelligence community. And it makes one wonder: Had we been able to realize how significant that was, put it together, and get it to the agencies that could have made use of it in time, would there have been a different end to the 9/11 story? Q: Was there information about some of the hijackers traveling to the U.S. that didn't get passed to the FBI? Hill: Well, the NSA had information about Nawaf al-Hazmi and Mihdhar early in 1999, and late in 1999 they handed off some of that to the CIA. The CIA then got information that Hazmi and Mihdhar were going to Kuala Lumpur for a meeting of Al Qaeda operatives. And after that meeting, the CIA learned that Hazmi and Mihdhar would be traveling to the United States. If you had information that two known Al Qaeda operatives were about to travel to the United States, I think most people would want to make sure that our law enforcement in this country, i.e., the FBI, was on the case. That didn't happen. Q: Why didn't it happen? Hill: Well, our report delves into the details of this instance. But what we found, broadly, was that the foreign intelligence agencies like CIA and NSA were more focused on what was going on overseas. Even though there was a great anticipation that there was going to be an attack on U.S. interests by Al Qaeda, most people believed it was going to be overseas. And so, tragically, their focus was on their job, which was looking overseas, and not so much on what was happening in the U.S., which they viewed as the FBI's job. "Analysts in NSA were still using index cards and pen and paper." There was a lack of information-sharing. That was a problem that we found endemic throughout this whole investigation, across the board, whether it was CIA, NSA, FBI. The intelligence agencies failed to share relevant information with one another, including this information about Mihdhar and Hazmi. They also failed to share it with other U.S. government agencies. And even more, they failed to share it with non-U.S. government agencies, like local law enforcement and police. TERRORISTS AMONG USQ: When Mihdhar and Hazmi arrived in the U.S. in January of 2000 and settled in San Diego, were they tracked at all? Hill: Even though their names were known to the CIA and NSA, nobody focused on them in the United States. There was no effort to track them until it was far too late. Ironically, during the time they were in San Diego, they had numerous contacts with a known, longtime FBI informant on counterterrorism issues. Now, had the FBI had those names and known that they were connected to Al Qaeda, the informant could have been tasked to surveil or approach those individuals to get more information. Frankly, who knows what would have happened. This was in 2000, long before the 9/11 attacks. As a former prosecutor, to me that was perhaps the single biggest opportunity they had to break this whole plot open long before the attacks of 9/11. It didn't happen, because the information was never shared. The informant was never asked about those individuals until long after 9/11. Q: According to your report, and as you mentioned, the NSA actually picked up communications that Khalid Mihdhar had with an Al Qaeda facility in the Middle East. The fact that he was not subsequently tracked in the U.S. seems astounding. Hill: Yes. Well, the Intelligence Community was aware that an individual known [in their internal records] as "Khaled" was contacting an Al Qaeda facility in the Middle East during 2000. That information was not passed on. And, more importantly, the significance of that information was never appreciated, because the intelligence community didn't realize that those contacts were coming from the United States. Q: When the NSA testified about this—claimed they had no idea that Mihdhar and the others were in the U.S.—was your committee skeptical? Hill: Well, I think it surprised some people. We asked them, as we asked the other agencies, a lot of hard questions. I have no reason to believe that they were misleading us. It was hard to believe, because we tend to assume that they know so much, and they have such advanced technological capabilities. But it didn't work that way. The NSA, at the time, also told us they did not want to focus on domestic U.S. activity. That was the FBI's job. Even though, I might add, NSA did have the ability, through the FISA court [a court that issues warrants to monitor suspected foreign agents] to cover certain communications coming from the U.S., as Mihdhar's were. NSA chose not to do that. KEEPING PACE WITH THE ENEMYQ: After Mihdhar and Hazmi left San Diego, they moved to Laurel, Maryland, ironically right near the NSA's home. They moved into a motel, where they planned the attack on the Pentagon. Should we be surprised that the NSA had no idea these terrorists were in their midst? Hill: Well, the public, I think for years, has viewed our intelligence community somewhat in awe. What they see in the movies makes it look like we have a huge intelligence community that's very powerful and at the cutting edge of technology. The public trusted that if something was going on, our intelligence community would know about it. 9/11 was a serious wake-up call. These people [the hijackers] were living in this country, able to live fairly normal lives—lease houses, apply for driver's licenses, apply for visas, go about their business—and pull off a very coordinated attack with a relatively small amount of resources against the most powerful country in the world. When we went back to reconstruct what happened, we realized that our great intelligence community, all the movies aside, was not able to stop this. It wasn't because we were operating against the world's most sophisticated intelligence service. We were operating against people who basically had hatched this plot in caves in Afghanistan, and who didn't have the technology and the resources and the money that this country had. So it was a rude awakening, and very hard to explain to the American people. It was hard even for us to comprehend when we did the review, and for the Congress to comprehend. But it happened. "NSA had 33 warnings about an imminent attack in the few months before 9/11." Q: Before 9/11, had the NSA kept up, technologically, to face the threat of terrorism? Hill: We found that it had not kept pace with advances in technology to really match the threat. NSA, and all our intelligence community, for years faced the threat of the Soviet Union, which was a very focused target. The target has changed immensely. When you're dealing with counterterrorism, you have groups that are not official state actors. They are all over the world. The intelligence that comes in—it's not a trickle; it's a flood. Part of the big challenge is keeping up with the technology to get a window into that world, as technology advances by leaps and bounds. [Learn about new technology the NSA is working on now.] Analysts in NSA were still using index cards and pen and paper. There were big holes. Also, their language capabilities were not where they should have been. Their readiness percentage in the language that would be used by terrorists was like 30 percent. That was also a problem at the FBI. Things weren't being translated at the FBI. So there were problems in technology, there were problems in language, there were problems in priorities. NSA had, at the time, 1,500 different requirements for intelligence collection. [NSA] Director [Michael] Hayden, I believe, testified that they had at least five number-one priorities. They had so many priorities that it was hard for them to decide which they had to focus most on. THE IMPENDING ATTACKQ: Did the intelligence agencies pick up messages indicating that the 9/11 attack was imminent? Hill: Our agencies did have information coming in, in the spring and summer of 2001, that there was going to be an attack of some sort on United States interests. They didn't know if it was overseas or domestic. They didn't have specifics—date, time, place, that kind of thing. But they had a lot of reports. NSA, I believe, had 33 warnings about an imminent attack in the few months before 9/11. [CIA Director] George Tenet told us that he was trying to get everybody focused on this. People told us this was the most traffic they had ever seen about a warning of an attack. NSA Director Hayden testified that within days of September 11th, the NSA actually got traffic indicating that there would be an attack on September 11th. They didn't have the place, or the time of day, or the type of attack, but they did have a specific warning that something would happen on September 11th. The irony is that even that information wasn't translated and disseminated until September 12th, after the attacks. So what does that tell you about our intelligence agencies' ability to react in real time? Not very good. Q: Did General Hayden, or anybody else from the NSA, try to explain why that happened—that this critical message wasn't translated until September 12th? Hill: He certainly was very candid about what happened. I don't recall any great detail as to the specifics, other than, again, they had a lot of information coming in. How do you figure out which one is the most important? How do you know whether this traffic is legitimate or significant or not? In some ways, it's looking for a needle in a haystack. And then, when you find the needle, you have to figure out what it really means and get it to the right people soon enough. It's a difficult job. Q: Did you sense that the NSA felt they had blown it? Or did they think there were legitimate reasons for why they failed to catch the plot? Hill: They were focused on overseas. Hayden talked about this, and you see it in our report time and again. Also, given the history of criticism of the intelligence community, they were very cautious about doing anything that would suggest that they were spying on Americans. I think that was driving a lot of this. The tragedy was that they had the capability and the authority, through the FISA Court, to do more. Even if they didn't use that authority, they could have done more with the FBI in terms of making sure the information was being handed off and followed up. Q: How skittish was the NSA about overstepping boundaries in domestic surveillance? Hill: I personally think that their concern about not being accused of spying on Americans was a big factor. I believe General Hayden when he says that. The problem is, when you deal with transnational threats like Al Qaeda, they don't stop at borders. It's not like you see the Russian army coming. It's a million different groups. They pass over in dribbles across borders. You have sleeper cells. You have sleeper groups. It's very, very hard to draw a hard-and-fast line between where foreign intelligence stops and domestic intelligence starts. That doesn't mean we want our foreign intelligence agencies on every street corner in America. But it does mean you have to have very good communication and coordination between the foreign intelligence agencies, like the CIA and NSA, and our domestic agencies, like the FBI. If you don't, things are going to slip between the cracks. They're going to get lost, and you're not going to cover everything. And that's exactly what happened with 9/11. FUTURE THREATSQ: Having spent several years of your life looking into this, what grade would you give the NSA in terms of doing their job leading up to 9/11? Hill: Well, I don't know if I should grade them on a curve by comparison to the other agencies. It's hard to grade any of these agencies. I certainly don't think I'd give them better than a C. Certainly it wasn't good enough. Q: So is the intelligence community culpable for allowing 9/11 to happen? Hill: After we issued our report, there were a lot of people who were angry at the intelligence community. But I think you have to remember that, as bad as the mishaps in our intelligence community were, I really believe those were unintentional mishaps. That doesn't excuse them, but we can't lose sight that the people who destroyed the Twin Towers and attacked the Pentagon, what they did was no mistake. It was intentional. Ultimately, the responsibility for 9/11 still lies with them. Q: Have the intelligence agencies corrected the problems that kept them from recognizing the 9/11 plot? Hill: They're certainly more sensitive to the problems. And there's been movement on a lot of the 9/11 Commission* recommendations and our report's recommendations, including the creation of the Director of National Intelligence, for example, and an expanded role for the Counterterrorism Center. I am not in government now. I'm not on the inside. I do hear from people in the intelligence community that things have improved. But we're not there completely yet. There are still problems. There are still issues in sharing information. You're still dealing with a huge intelligence community, lots of different agencies. You're still dealing with a threat that involves a vast amount of information, a vast number of different terrorist groups. It's a very hard threat to deal with. I would say we're safer. But we're not perfectly safe by any means.

*Editor's note: Hill's Joint Congressional Inquiry pre-dated

the 9/11 Commission, which had a broader focus beyond

examining the intelligence community. |

A year after the September 11th attacks, Eleanor Hill coordinated the congressional hearings that examined what, if anything, the intelligence community might have done to stop the plot.

While the National Security Agency recognized the mounting threat of Osama bin Laden and Al Qaeda, the agency had been founded during the Cold War and was ill-prepared to monitor this new type of enemy.

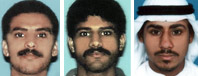

By the end of 1999, the NSA had the names of three of the hijackers, Khalid al-Mihdhar, Nawaf al-Hazmi, and Salem al-Hazmi (left to right).

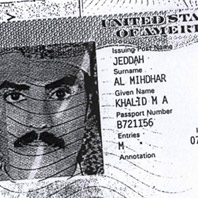

The NSA and CIA knew of Mihdhar's association with Al Qaeda, yet he was able to obtain a U.S. visa repeatedly.

While living in San Diego, Nawaf al-Hazmi and Mihdhar took flight-training classes at the National Air College on Glenn Curtis Road.

According to his research, James Bamford believes that this house in Yemen served as the Al Qaeda base that the hijackers contacted.

As they plotted their attack on the Pentagon, Nawaf al-Hazmi and Mihdhar stayed at the low-budget Valencia Motel, just miles from the NSA's headquarters.

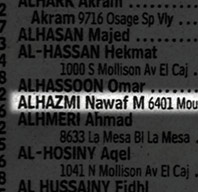

This listing in a San Diego phone book shows how little some of the hijackers did to hide their tracks. |

|

|

|

|

Interview conducted on August 25, 2008 in Washington, D.C. by James Bamford and edited by Susan K. Lewis, senior editor of NOVA Online. The Spy Factory Home | Send Feedback | Image Credits | Support NOVA |

© | Created January 2009 |

|

|

|