|

Seahorse Crusader Amanda Vincent

"They were a heck of a couple, really exciting for six minutes a

day..."

NOVA: Can you talk a little bit about how you got interested in seahorses and

what sort of life you lead as a scientist?

AV: I suppose I study seahorses for three reasons. Initially, I started

studying them because I wanted to work with the sea, and I wanted to use my

brain. And I wanted to be outdoors. Then I had an academic interest in the

evolution of sex differences—and in seahorses only the male gets pregnant,

which of course raises a lot of questions about sex differences. And then the

third reason is that, as I began to work with seahorses, I became completely

addicted to the little creatures and now I would find it very hard to move my

attention away from them and their relatives. I did an undergraduate degree

and then I traveled around the world for quite a few years not really doing

biology just getting more experience of different cultures and different

places, which has been very useful in the long run. I went back and did a

Ph.D.. After I finished my Ph.D. I then went and did a research fellowship at

Oxford in England, and had a lot of freedom to explore ideas that interested

me. So I went off to Australia and did a lot of field work on the seahorses.

And while I was doing that, I began to get frightened about what I perceived to

be a really big trade in these animals. I looked around and I found that there

weren't any data at all, that there weren't formal trade records, nobody knew

anything about the trade, and realized I wanted to work with this. I was very

lucky because National Geographic Magazine had invited me to write an article

and offered to fund a trip to look into the possible trade. So I was able to

go around Asia visiting all the little fishing villages and the traders, the

importers, the exporters, the biologists, the fisheries officers asking them

what they knew about the seahorse trade. And my goal, I suppose is very much

to alert people to the problems of marine conservation. So by working with

seahorses I get to work with animals that I'm really hooked on, that I really

like. I have some qualifications for becoming involved in a whole range of

issues in marine conservation. And I have an excuse for working in the tropics

for part of the year, particularly during the Canadian winter.

AV: I suppose I study seahorses for three reasons. Initially, I started

studying them because I wanted to work with the sea, and I wanted to use my

brain. And I wanted to be outdoors. Then I had an academic interest in the

evolution of sex differences—and in seahorses only the male gets pregnant,

which of course raises a lot of questions about sex differences. And then the

third reason is that, as I began to work with seahorses, I became completely

addicted to the little creatures and now I would find it very hard to move my

attention away from them and their relatives. I did an undergraduate degree

and then I traveled around the world for quite a few years not really doing

biology just getting more experience of different cultures and different

places, which has been very useful in the long run. I went back and did a

Ph.D.. After I finished my Ph.D. I then went and did a research fellowship at

Oxford in England, and had a lot of freedom to explore ideas that interested

me. So I went off to Australia and did a lot of field work on the seahorses.

And while I was doing that, I began to get frightened about what I perceived to

be a really big trade in these animals. I looked around and I found that there

weren't any data at all, that there weren't formal trade records, nobody knew

anything about the trade, and realized I wanted to work with this. I was very

lucky because National Geographic Magazine had invited me to write an article

and offered to fund a trip to look into the possible trade. So I was able to

go around Asia visiting all the little fishing villages and the traders, the

importers, the exporters, the biologists, the fisheries officers asking them

what they knew about the seahorse trade. And my goal, I suppose is very much

to alert people to the problems of marine conservation. So by working with

seahorses I get to work with animals that I'm really hooked on, that I really

like. I have some qualifications for becoming involved in a whole range of

issues in marine conservation. And I have an excuse for working in the tropics

for part of the year, particularly during the Canadian winter.

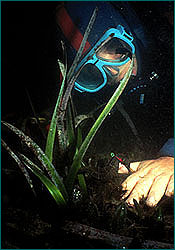

NOVA: I know that, during your field work in Australia, you sometimes spent as

much as twelve hours a day underwater observing seahorses. What was that

like?

AV: Getting up in the morning at 4:30 isn't a whole lot of fun, and pulling on

a wet suit that's still rather damp and smelly from the day before is even less

fun. It used to be a real struggle to get in the water. But somehow my

assistants and I would make it in before dawn. And you'd float out over this

ghostly set of seagrass meadows knowing that the animals you knew as

individuals were down there. And then came the challenge of trying to find

them each morning. And I have to say that it got pretty embarrassing because

you knew where they should be, and yet you would go round and round that little

bit of seagrass until eventually you suddenly caught sight of a little tail tip

and then you'd sit and watch them. And your mind would play funny tricks.

Sometimes I'd be watching the seahorses for three hours, six hours, nine hours.

It was very hard not to make up a soap opera about the animals you were

watching. You knew that any moment now little Harry would put his head up and

Mabel would come swimming over the horizon up to him, and they'd dance together

for a little while holding tails and they'd be ever so happy and then they'd

separate for the rest of the day. And then you wondered whether Mabel was

getting up to hanky-panky with anyone else. You discovered eventually that no,

she wasn't. In fact, she spent her whole day feeding, and so did Harry. So

they were a heck of a couple, really exciting for six minutes a day, and

otherwise dreary as hell. Then on the day that Harry had given birth, Mabel

would appear with a load of eggs. And they'd go into this nine hour ballet.

They'd just be pivoting and dancing and twirling and rising and changing colors

and lifting their heads and it was very, very beautiful, and somehow you didn't

even realize nine hours had gone past. And there they were mating. So I guess

watching seahorses requires a very calm spirit. And if you're not a calm

person, and I'm not, then I'm sure it's very good for the soul, because you

basically just go into a meditative state for the whole time.

you knew where they should be, and yet you would go round and round that little

bit of seagrass until eventually you suddenly caught sight of a little tail tip

and then you'd sit and watch them. And your mind would play funny tricks.

Sometimes I'd be watching the seahorses for three hours, six hours, nine hours.

It was very hard not to make up a soap opera about the animals you were

watching. You knew that any moment now little Harry would put his head up and

Mabel would come swimming over the horizon up to him, and they'd dance together

for a little while holding tails and they'd be ever so happy and then they'd

separate for the rest of the day. And then you wondered whether Mabel was

getting up to hanky-panky with anyone else. You discovered eventually that no,

she wasn't. In fact, she spent her whole day feeding, and so did Harry. So

they were a heck of a couple, really exciting for six minutes a day, and

otherwise dreary as hell. Then on the day that Harry had given birth, Mabel

would appear with a load of eggs. And they'd go into this nine hour ballet.

They'd just be pivoting and dancing and twirling and rising and changing colors

and lifting their heads and it was very, very beautiful, and somehow you didn't

even realize nine hours had gone past. And there they were mating. So I guess

watching seahorses requires a very calm spirit. And if you're not a calm

person, and I'm not, then I'm sure it's very good for the soul, because you

basically just go into a meditative state for the whole time.

NOVA: Are seahorses plentiful off American shores?

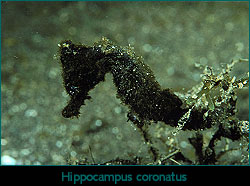

AV: There are approximately four species around North America down to South

America. They range in size from a very small species, sometimes known as the

dwarf seahorse, which is only about an inch long, up to a species off the

Pacific Coast of Central America which gets to be about a foot long called

Hippocampus ingens. And then there's Hippocampus reidi, which is found in the

Caribbean in coral reefs. It's quite a slender, but quite large seahorse and

one of my favorite species, because when they dance they turn these fluorescent

neon colors. And then Hippocampus erectus is quite a big chunky seahorse and

it's found from Nova Scotia all the way down to perhaps Uruguay. The seahorses

around the Americas are often caught by mistake in troll nets, especially those

that are seeking live shrimp for bait. They're also caught intentionally for

aquarium trade. We know that Florida had at least 112,000 seahorses landed in

1994. We don't know quite what was done with them. But the Taiwanese customs

data, which are the only data in the world for seahorses, show that they

imported seahorses from North America for medicines. And we think many of

those may come from Florida.

AV: There are approximately four species around North America down to South

America. They range in size from a very small species, sometimes known as the

dwarf seahorse, which is only about an inch long, up to a species off the

Pacific Coast of Central America which gets to be about a foot long called

Hippocampus ingens. And then there's Hippocampus reidi, which is found in the

Caribbean in coral reefs. It's quite a slender, but quite large seahorse and

one of my favorite species, because when they dance they turn these fluorescent

neon colors. And then Hippocampus erectus is quite a big chunky seahorse and

it's found from Nova Scotia all the way down to perhaps Uruguay. The seahorses

around the Americas are often caught by mistake in troll nets, especially those

that are seeking live shrimp for bait. They're also caught intentionally for

aquarium trade. We know that Florida had at least 112,000 seahorses landed in

1994. We don't know quite what was done with them. But the Taiwanese customs

data, which are the only data in the world for seahorses, show that they

imported seahorses from North America for medicines. And we think many of

those may come from Florida.

NOVA: How hard is it to strap on a snorkel and go have a look at these little

creatures?

AV: Well, the first field work I tried to do on seahorses was in Florida in

1986. And it was a screaming embarrassment because I just couldn't find the

animals. I mean it was really mortifying. To be underwater as, supposedly, a

seahorse biologist and I couldn't find them! Eventually I got better at it.

NOVA: What's so tricky about it?

AV: They're very, very cryptic animals. Seahorses can change color to match

their background. They grow long skin appendages so that they blend in better

with the algae. They let encrusting organisms settle on them. They're just

really well camouflaged. You always look for the tail, because the tail wraps

all the way around whatever it's holding, whereas the head and the eye can be

hidden.

AV: They're very, very cryptic animals. Seahorses can change color to match

their background. They grow long skin appendages so that they blend in better

with the algae. They let encrusting organisms settle on them. They're just

really well camouflaged. You always look for the tail, because the tail wraps

all the way around whatever it's holding, whereas the head and the eye can be

hidden.

NOVA: What evolutionary purpose does monogamous pair bonding and male

pregnancy provide for seahorses?

AV: It's always an awkward question as to why animals are monogamous. Very

few animals stick with one partner for life. Humans are unusual in that

respect. In fishes, monogamy is particularly rare. So it was a bit surprising

to find that seahorses were monogamous. We have evidence suggesting that when

seahorses stick with a partner for a while they get better at producing babies

as a team.

NOVA: And what about male pregnancy?

AV: Well, we tend to think of parental care as being the responsibility of the

female, but that's because we're mammals. In birds, if you think about it,

both parents usually care for the young. And in fishes, people are often

surprised to learn that usually the parental care is given only by the male.

Now parental care in fishes usually involves just guarding the eggs, fanning

the eggs, making sure they get enough oxygen and they're clean. The seahorses

are the most extreme example of fathers providing the care that we know in the

animal world. Because they guard the eggs all right, but they guard them on

their body. They also provide oxygen through a capillary network in the pouch,

and they also transfer nutrients, and they control the pouch environment so

that it changes during the pregnancy to become more like salt water. This then

is an extreme example, but presumably instead of producing many small young,

the seahorses produce fewer, but better developed and larger young.

NOVA: Seahorses are not, technically speaking, endangered, are they?

AV: Well, we've listed virtually all seahorses on the 1996 International Union

for the Conservation of Nature "red list." And the "red list" acts like a

flag. It warns you that species are considered to be at risk, without

enforcing any regulations. We know that the seahorse populations we've been

able to examine are declining quite dramatically—on the order of 25 to 50

percent over five years.

NOVA: Where are all these seahorses going?

AV: There's tremendous difficulty with consumption of seahorses for

traditional Chinese medicines, for the aquarium trade and also for curiosities

and souvenirs. Traditional Chinese medicine is the biggest user of seahorses,

and the numbers involved in that trade may amount to more than 20 million a

year. I should point out, it's not just ethnic Chinese communities—seahorses are also used as medicines by the Indonesians, the Central Filipinos,

and a whole host of other racial and ethnic groups around the world. Hundreds

of thousands of seahorses are used each year, as well, for the aquarium trade.

And the aquarium trade is primarily driven by North American consumption. Most

of these seahorses are juveniles, they haven't even bred, they haven't even

reproduced when we buy them and put them in our home aquariums, where they

usually die. And then the curiosity trade is, again, hundreds of thousands of

animals each year. It's pretty hard to justify having a seahorse on a key

chain or on your mantelpiece when you know that's depleting wild populations.

And seahorses live in some of the world's most threatened habitats: sea

grasses, mangroves, coral reefs and estuaries. We're working very hard to draw

attention to the habitat loss.

and the numbers involved in that trade may amount to more than 20 million a

year. I should point out, it's not just ethnic Chinese communities—seahorses are also used as medicines by the Indonesians, the Central Filipinos,

and a whole host of other racial and ethnic groups around the world. Hundreds

of thousands of seahorses are used each year, as well, for the aquarium trade.

And the aquarium trade is primarily driven by North American consumption. Most

of these seahorses are juveniles, they haven't even bred, they haven't even

reproduced when we buy them and put them in our home aquariums, where they

usually die. And then the curiosity trade is, again, hundreds of thousands of

animals each year. It's pretty hard to justify having a seahorse on a key

chain or on your mantelpiece when you know that's depleting wild populations.

And seahorses live in some of the world's most threatened habitats: sea

grasses, mangroves, coral reefs and estuaries. We're working very hard to draw

attention to the habitat loss.

NOVA: How much are seahorses worth? How much do they trade for?

AV: Seahorses are becoming very valuable. The best quality seahorses in

traditional Chinese medicine—the smooth pale, large seahorses—now sell in

Hong Kong for up to $550 U.S. per pound. Even the seahorses that are not quite

such good quality are selling for a couple of hundred dollars per pound. There

are about 39 countries around the world now involved in the seahorse trade,

most of them trading dried seahorses for traditional Chinese medicine. So this

is becoming quite big business, which is part of the problem.

NOVA: Is there any evidence that, chemically, there is something unique in

seahorses that is medicinal?

AV: Traditional Chinese medicine doesn't usually do western-style

pharmacological testing. Instead they tend to rely on past efficacy, past

treatments and how they've worked. So there's a strong conviction that

seahorses are one of the fundamentals of traditional Chinese medicine, but

there's not any testing in a way that we would recognize as double-blind

medical testing. Certainly there are Chinese medical treatments which have

been well tested in the west and are proving incredibly useful. So it would be

nice to investigate thoroughly the real value of seahorses.

(continued)

Seahorse Home | Crusader | Basics | Superdads

Roundup | Resources | Table of Contents

|