|

NOVA: Are they used mainly as aphrodisiacs?

NOVA: Are they used mainly as aphrodisiacs?

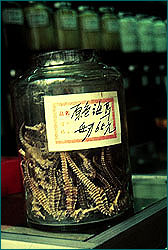

AV: No, they're used for a whole range of ailments. Seahorses are used to

treat asthma, and arteriosclerosis, and incontinence and impotence and thyroid

disorders and skin ailments and broken bones and heart disease. And even to

facilitate childbirth, although it depends a little bit on the region. In Hong

Kong, they're used primarily for asthma and for impotence. In Taiwan they're

used an awful lot for an aphrodisiac or to promote sexual function.

NOVA: What sort of testimonials have you heard from people who have used

seahorses and found them effective?

AV: We've talked a lot to traditional Chinese medicine users and they're

convinced that seahorses work, which is one reason why we don't take the

arrogant perspective of dismissing it as superstitious nonsense. Instead we're

trying very hard to set up a new approach whereby we respect the conviction

that these are medically useful, at the same time pointing out that the loss of

these animals in wild populations would penalize Chinese medicine as much as it

would penalize those who respect them for their conservation value. Really,

when you think about it, the people who catch the seahorses need there still to

be seahorses so that they can continue earning an income. The people who use

seahorses for medicines need there still to be seahorses to treat their

illnesses. And we, who primarily are concerned about the conservation issues,

want there to be seahorses. And there's got to be a way of harnessing these

three different converging needs for seahorses in the wild.

trying very hard to set up a new approach whereby we respect the conviction

that these are medically useful, at the same time pointing out that the loss of

these animals in wild populations would penalize Chinese medicine as much as it

would penalize those who respect them for their conservation value. Really,

when you think about it, the people who catch the seahorses need there still to

be seahorses so that they can continue earning an income. The people who use

seahorses for medicines need there still to be seahorses to treat their

illnesses. And we, who primarily are concerned about the conservation issues,

want there to be seahorses. And there's got to be a way of harnessing these

three different converging needs for seahorses in the wild.

NOVA: You just got back from Asia?

AV: Yes, I just got back at the end of February 1997.

NOVA: Where were you and what were you doing?

AV: I was in the Philippines and Vietnam and Hong Kong. In Vietnam, I was

checking up on a project I have there with four biologists from the Institute

of Oceanography. We're just beginning village training on raising seahorses in

captivity with the idea of providing local fishers with an alternative to

catching the wild seahorses.

NOVA: I understand that raising seahorses in tanks is a real challenge. Why

is that?

AV: Seahorses are tricky little creatures. They need to eat live food only.

They're really voracious predators contrary to their sort of pleasant benign

appearance. And seahorses also get a lot of diseases. So rearing baby

seahorses is an exercise in trying to draw together a whole host of different

tiny food sources, which means you have to culture the algae to feed the little

food items to feed the seahorses. And it's complicated to do that well enough

to have reliable supplies for large numbers of animals.

NOVA: What are you working on in the Philippines?

AV: In the Philippines I work with a non-governmental organization called the

Haribon Foundation for the conservation of natural resources. We just launched

a new initiative which we're calling "grow-out cages." The grow-out cages are

corrals in the sea, built by the fishers from confiscated nets from people

who've been fishing illegally. The fishers have to continue catching the very

small seahorses, the juveniles, because if they don't catch them other people

in the region will. And these fishers need the income desperately to provide

the rice for their families. So now we have an agreement whereby when they

catch these juvenile seahorses, they will be paid from a small loan we've given

them. But the seahorses will not be sold. Instead they're going to be put

into these corrals in the sea, and they'll grow up there for five months. At

the end of that time, the fishers will pay us back the loan, but they'll be

able to sell the seahorses for double the initial value, because now they're

larger. So this gives the fishers more money. The advantage to conservation

is that halfway during this grow-out period, the seahorses will start

reproducing. So for about two and a half months, the seahorses in the corrals

will be releasing their young into the sea. The young will escape through the

nets and re-populate the wild regions.

small seahorses, the juveniles, because if they don't catch them other people

in the region will. And these fishers need the income desperately to provide

the rice for their families. So now we have an agreement whereby when they

catch these juvenile seahorses, they will be paid from a small loan we've given

them. But the seahorses will not be sold. Instead they're going to be put

into these corrals in the sea, and they'll grow up there for five months. At

the end of that time, the fishers will pay us back the loan, but they'll be

able to sell the seahorses for double the initial value, because now they're

larger. So this gives the fishers more money. The advantage to conservation

is that halfway during this grow-out period, the seahorses will start

reproducing. So for about two and a half months, the seahorses in the corrals

will be releasing their young into the sea. The young will escape through the

nets and re-populate the wild regions.

NOVA: How much money is involved in the loans?

AV: Oh, they're micro loans. I mean tiny amounts. For example, each baby

seahorse that comes in is worth three pesos. And that's about 12 cents. And

we expect to have two to three hundred seahorses in each corral. So we're not

talking about huge amounts of money. But for the fishers, it's an

insurmountable amount to raise themselves. We recognize that the reason

people fish the seahorses too heavily is the lack of other economic

alternatives and the lack of education to find other alternatives. So another

thing we've done is set up high school scholarships. In our village, very,

very few children make it to high school—less than ten kids were at high

school. So we provided the opportunity for two more kids to go to high school,

and in exchange they spend every weekend with us as apprentices in

conservation, working on the project and communicating what we're doing to

other villagers and leading programs for younger children in marine

conservation, particularly with respect to seahorses.

talking about huge amounts of money. But for the fishers, it's an

insurmountable amount to raise themselves. We recognize that the reason

people fish the seahorses too heavily is the lack of other economic

alternatives and the lack of education to find other alternatives. So another

thing we've done is set up high school scholarships. In our village, very,

very few children make it to high school—less than ten kids were at high

school. So we provided the opportunity for two more kids to go to high school,

and in exchange they spend every weekend with us as apprentices in

conservation, working on the project and communicating what we're doing to

other villagers and leading programs for younger children in marine

conservation, particularly with respect to seahorses.

NOVA: And what about your work in Hong Kong?

AV: In Hong Kong we're considering starting a new project. There the idea

would be to hire somebody who is ethnic Chinese to work with the traditional

medicine community in Hong Kong and China in order to discuss with them

possibilities that could replace seahorses. So to look through their

repertoire of medical alternatives to seek species that are not at risk and

encourage medical use of those instead of seahorses.

NOVA: Are people generally receptive to what you're trying to do?

AV: Doing community based work in Vietnam is complicated because the political

tradition recently hasn't allowed for much individual input. Working with

communities in the Philippines is a lot easier because the Philippines has a

long tradition of community-based work. We find that villagers usually can

identify the problems at least as quickly as we can. So it's not that fishers

don't recognize they are over-fishing. They do. But they're extremely poor.

Our focal community in the Philippines is one of the poorest villages in a poor

municipality in a poor province of a very poor country. And seahorses provide

about half the annual cash income for about a quarter of the households in the

village. Clearly they're an important resource. When we discuss with the

fishers ways forward they're full of suggestions and very happy to evaluate our

suggestions and then try the ones that we mutually feel are possible. The

Our focal community in the Philippines is one of the poorest villages in a poor

municipality in a poor province of a very poor country. And seahorses provide

about half the annual cash income for about a quarter of the households in the

village. Clearly they're an important resource. When we discuss with the

fishers ways forward they're full of suggestions and very happy to evaluate our

suggestions and then try the ones that we mutually feel are possible. The

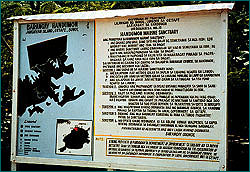

villagers set up a marine sanctuary for all species, not just for seahorses.

And it's been strictly their baby. They've policed it, they've enforced it,

and they're very proud, as they should be, of its rather rapid recovery. The

fishing around the reserve has now gone up, and this means that more and more

villagers believe that this is a good idea. To the point where other villages

are now asking our involvement to establish their own sanctuaries because

they've heard from their friends and seen with their own eyes how much

difference it makes.

villagers set up a marine sanctuary for all species, not just for seahorses.

And it's been strictly their baby. They've policed it, they've enforced it,

and they're very proud, as they should be, of its rather rapid recovery. The

fishing around the reserve has now gone up, and this means that more and more

villagers believe that this is a good idea. To the point where other villages

are now asking our involvement to establish their own sanctuaries because

they've heard from their friends and seen with their own eyes how much

difference it makes.

NOVA: That must be gratifying.

AV: It's really nice to see. Just to realize that you're meeting a need and

to be asked for help instead of to try to encourage them to accept help.

NOVA: And in Hong Kong?

AV: In Hong Kong, we've found that the traditional Chinese medicine community

is very happy to discuss ways of addressing conservation concerns. There's

been a long history of confrontation between conservationists and traditional

medicine communities. TRAFFIC, which is the international agency that monitors

the trade in endangered animals and plants, started a new dialogue, a new

paradigm about a year and a half ago when they arranged a workshop with the

traditional medicine community and conservationists with simultaneous

translation. And they found that once discussion began, the Chinese medicine

community was very receptive. But it is not in the Chinese culture to be

aggressively confrontational, which is the way most western conservation bodies

had addressed the issue. So we find when we sit down with a bit of give and

take in a dialogue there is a willingness to discuss possible ideas, and we're

hoping to capitalize on that by developing a new program to adjust the demand

for seahorses which is growing extremely rapidly—mostly because of China's

economic growth.

medicine communities. TRAFFIC, which is the international agency that monitors

the trade in endangered animals and plants, started a new dialogue, a new

paradigm about a year and a half ago when they arranged a workshop with the

traditional medicine community and conservationists with simultaneous

translation. And they found that once discussion began, the Chinese medicine

community was very receptive. But it is not in the Chinese culture to be

aggressively confrontational, which is the way most western conservation bodies

had addressed the issue. So we find when we sit down with a bit of give and

take in a dialogue there is a willingness to discuss possible ideas, and we're

hoping to capitalize on that by developing a new program to adjust the demand

for seahorses which is growing extremely rapidly—mostly because of China's

economic growth.

NOVA: What mysteries are left with regard to seahorses?

AV: There's so much we don't know about seahorses that I hardly know where to

begin explaining it to you. Believe it or not we don't know how long they

live. We don't know whether males and females eat differently. We don't know

if pregnant males eat differently. We don't know about their growth rates over

their life. We don't know a whole lot about what determines how many young the

seahorses actually have and whether some conditions will favor them producing

better and more young. We don't know how they choose their partners initially

when they want to pair. We don't know very much about what eats them. Believe

it or not, I did the first underwater study on seahorses as a biologist only

about six or seven years ago. And we still only have one or two other studies

in the whole world going on underwater for about 35 species of seahorse. So we

haven't even studied most seahorses in the wild. There's almost a limitless

list of questions that people can address.

NOVA: Where can people interested in seahorses get more information?

AV: Two colleagues, Dr. Heather Stanley and Dr. Helen Hall, and I have formed

an umbrella program called Project Seahorse. Our Web site is at

http://www.anyware.co.uk/seahorses/ and if anybody is interested, obviously

we'd love to hear from them.

Photos: (1-2, 4-12) © Amanda Vincent; (3) © James Beveridge/Visuals Unlimited.

Seahorse Home | Crusader | Basics | Superdads

Roundup | Resources | Table of Contents

|