|

|

|

Erected in 756 A.D., Stela M portrays Smoke Shell, the 15th ruler of Copán.

|

Incidents of Travel

Edgar Allan Poe called it "perhaps the most interesting book of travel ever published." The historian David McCullough deemed it "a classic, thrilling piece of work [that] can be seen as the beginning of American archeology." It is Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatán, by John Lloyd Stephens. A lawyer ostensibly on a mission for the U.S. State Department, Stephens, in 1839, went in search of Mayan ruins, which were then all but unknown. He was accompanied by architect Frederick Catherwood, whose meticulous drawings grace both Stephens' book and the passages excerpted below. Here, in introspective and highly impassioned prose, Stephens describes coming upon the ruined city of Copan, which he found so captivating that he promptly purchased the site—today owned by the Honduran government—from its then owner, an Indian named Don Jose Maria.

We came to the bank of a river, and saw directly opposite a stone wall, perhaps 100 feet high, with furze [a type of shrub] growing out of the top, running north and south along the river, in some places fallen, but in others entire. It had more the character of a structure than any we had ever seen ascribed to the aborigines of America, and formed part of the wall of Copan, an ancient city on whose history books throw but little light.

Stela P is a portrait of Butz' Chan (Smoke Snake or Smoke Sky), who reigned for 50 years until his death on January 23, 628.

|

|

The wall was of cut stone, well laid, and in a good state of preservation. We ascended by large stone steps, in some places perfect, and in others thrown down by trees which had grown up between the crevices, and reached a terrace, the form of which it was impossible to make out, from the density of the forest in which it was enveloped. Our guide cleared a way with his machete, and we passed, half buried in the earth, a large fragment of stone elaborately sculptured, and came to the angle of a structure with steps on the sides, in form and appearance, so far as the trees would enable us to make it out, like the sides of a pyramid.

Diverging from the base, and working our way through the thick woods, we came upon a square stone column, about 14 feet high and three feet on each side, sculptured in very bold relief, and all four sides, from the base to the top. The front was the figure of a man curiously and richly dressed, and the face, evidently a portrait, solemn, stern, and well fitted to excite terror. The back was of a different design, unlike anything we had ever seen before, and the sides were covered with hieroglyphics. This our guide called an "Idol;" and before it, at a distance of three feet, was a large block of stone, also sculptured with figures and emblematical devices, which he called an altar.

The sight of this unexpected monument put at rest at once and forever, in our minds, all uncertainty in regard to the character of American antiquities, and gave us the assurance that the objects we were in search of were interesting, not only as the remains of an unknown people, but as works of art, proving, like newly discovered historical records, that the people who once occupied the Continent of America were not savages.

|

Copán, Stephens wrote, "lay before us like a shattered bark in the midst of the ocean [with] none to tell whence she came..."

|

City of silence

We followed our guide, who, with a constant and vigorous use of his machete, conducted us through the thick forest, among half-buried fragments, to 14 monuments of the same character and appearance, some with more elegant designs, and some in workmanship equal to the finest monuments of the Egyptians; one displaced from its pedestal by enormous roots; another locked in the close embrace of branches of trees, and almost lifted out of the earth; another hurled to the ground, and bound down by huge vines and creepers; and one standing, with its altar before it, in a grove of trees which grew around it, seemingly to shade and shroud it as a sacred thing; in the solemn stillness of the woods, it seemed a divinity mourning over a fallen people. The only sounds that disturbed the quiet of this buried city were the noise of monkeys moving among the tops of the trees.

Architecture, sculpture, and painting, all the arts which embellish life, had flourished in this overgrown forest; orators, warriors, and statesmen, beauty, ambition, and glory, had lived and passed away, and none knew that such things had been, or could tell of their past existence. Books, the records of knowledge, are silent on this theme. The city was desolate.

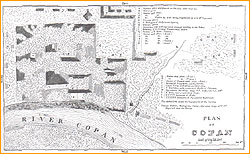

Like all his work, Catherwood's map of Copán is exquisitely drawn (though, strangely, north lies in the direction south should be and vice versa).

|

|

No remnant of this race hangs round the ruins, with traditions handed down from father to son, and from generation to generation. It lay before us like a shattered bark in the midst of the ocean, her masts gone, her name effaced, her crew perished, and none to tell whence she came, to whom she belonged, how long on her voyage, or what caused her destruction; her lost people to be traced only by some fancied resemblance in the construction of the vessel, and, perhaps never to be known at all. The place where we sat, was it a citadel from which an unknown people had sounded the trumpet of war? or a temple for the worship of the God of peace? or did the inhabitants worship the idols made with their own hands, and offer sacrifices on the stones before them? All was mystery, dark, impenetrable mystery, and every circumstance increased it.

It is impossible to describe the interest with which I explored these ruins. The ground was entirely new; there were no guide-books or guides; the whole was virgin soil. We could not see ten yards before us, and never knew what we should stumble upon next. At one time we stopped to cut away branches and vines which concealed the face of a monument, and then to dig around and bring to light a fragment, a sculptured corner of which protruded from the earth. I leaned over with breathless anxiety while the Indians worked, and an eye, an ear, a foot, or a hand was disentombed. When the machete rang against the chiseled stone, I pushed the Indians away, and cleared out the loose earth with my hands. The beauty of the sculpture, the solemn stillness of the woods, disturbed only by the scrambling of monkeys and chattering of parrots, the desolation of the city, and the mystery that hung over it, all created an interest higher, if possible, than I had ever felt among the ruins of the Old World.

Continue: Buying Copán

Map of the Maya World |

Incidents of Travel

Tour Copán with David Stuart |

Reading Maya Hieroglyphs

Resources |

Transcript |

Site Map |

Lost King of the Maya Home

Editor's Picks |

Previous Sites |

Join Us/E-mail |

TV/Web Schedule

About NOVA |

Teachers |

Site Map |

Shop |

Jobs |

Search |

To print

PBS Online |

NOVA Online |

WGBH

© | Updated February 2001

|

|

|