|

|

|

John Lloyd Stephens, circa 1840.

|

Incidents of Travel

Part 2 | Back to Part 1

Buying Copan

Mr. Catherwood went to the ruins to continue his drawings, and I to the village. My first visit was to Don Jose Maria. After clearing up our character, I broached the subject of a purchase of the ruins; told him that, on account of my public business, I could not remain as long as I desired, but wished to return with spades, pickaxes, ladders, crowbars, and men, build a hut to live in, and make a thorough exploration; that I could not incur the expense at the risk of being refused permission to do so; and, in short, in plain English, asked him, What will you take for the ruins?

I think he was not more surprised than if I had asked to buy his poor old wife to practice medicine upon. The property was so utterly worthless that my wanting to buy it seemed very suspicious. On examining the paper, I found that he did not own the fee, but held under a lease from Don Bernardo de Aguile, of which three years were unexpired. The tract consisted of about 6,000 acres, for which he paid 80 dollars a year; he was at a loss what to do, but he told me that he would reflect upon it, consult his wife, and give me an answer at the hut.

The reader is perhaps curious to know how old cities sell in Central America. Like other articles of trade, they are regulated by the quantity in market, and the demand; but, not being staple articles, like cotton and indigo, they were held at fancy prices, and at that time were dull of sale. I paid 50 dollars for Copan. There was never any difficulty about price. I offered that sum, for which Don Jose Maria thought me only a fool; if I had offered more, he would probably have considered me something worse.

The people of Copan could not comprehend what we were about, and thought we were practicing some black art to discover hidden treasure. Even the monkeys seemed embarrassed and confused. They were grave and solemn as if officiating as the guardians of consecrated ground. In the morning they were quiet, but in the afternoon they came out for a promenade on the tops of the trees; and sometimes, as they looked steadfastly at us, they seemed on the point of asking us why we disturbed the repose of the ruins.

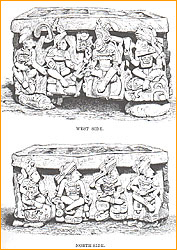

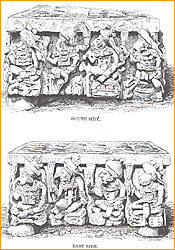

The four sides—and 16 kings—of Altar Q.

|

|

Idol speculation

Of the moral effect of the monuments themselves, standing as they do in the depths of tropical forest, silent and solemn, strange in design, excellent in sculpture, rich in ornament, different from the works of any other people, their uses and purposes, their whole history so entirely unknown, with hieroglyphics explaining all, but perfectly unintelligible, I shall not pretend to convey any idea. Often the imagination was pained in gazing at them. The tone which pervades the ruins is that of deep solemnity. An imaginative mind might be infected with superstitious feelings.

From constantly calling them by that name in our intercourse with the Indians, we regarded these solemn memorials as "idols"—deified kings and heroes—objects of adoration and ceremonial worship. We did not find on either of the monuments or sculptured fragments any delineations of human, or, in fact, any other kind of sacrifice, but had no doubt that the large sculptured stone invariably found before each "idol" was employed as a sacrificial altar. The form of sculpture most frequently met with was a death's head, sometimes the principal ornament, and sometimes only accessory; whole rows of them on the outer wall, adding gloom to the mystery of the place, keeping before the eyes of the living death and the grave, presenting the idea of a holy city—the Mecca or Jerusalem of an unknown people.

In regard to the age of this desolate city I shall not at present offer any conjecture. Some idea might perhaps be formed from the accumulations of earth and the gigantic trees growing on top of the ruined structures, but it would be uncertain and unsatisfactory.

|

As Stephens surmised, Copán's history is indeed graven on its monuments.

|

Nor shall I at this moment offer any conjecture in regard to the people who built it, or to the time when or the means by which it was depopulated, and became a desolation and ruin; whether it fell by the sword, or famine, or pestilence. The trees which shroud it may have sprung from the blood of its slaughtered inhabitants; they may have perished howling with hunger; or pestilence, like the cholera, may have piled its streets with dead, and driven forever the feeble remnants from their homes; of which dire calamities to other cities we have authentic accounts, in eras both prior and subsequent to the discovery of the country by the Spaniards. One thing I believe, that its history is graven on its monuments. Who shall read them?

Excerpted with permission from Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatan, by John Lloyd Stephens (Smithsonian Institution Press, 1993).

Map of the Maya World |

Incidents of Travel

Tour Copán with David Stuart |

Reading Maya Hieroglyphs

Resources |

Transcript |

Site Map |

Lost King of the Maya Home

Editor's Picks |

Previous Sites |

Join Us/E-mail |

TV/Web Schedule

About NOVA |

Teachers |

Site Map |

Shop |

Jobs |

Search |

To print

PBS Online |

NOVA Online |

WGBH

© | Updated February 2001

|

|

|