|

|

|

by Brenda Fowler The Iceman did not die on a full stomach. Eight hours before his death on a barren Alpine pass, he was in the valley to the south, in what is today Italy's Schnals Valley. There, according to Dr. Klaus Oeggl, a botanist from the University of Innsbruck who recently examined his gut contents, the man took his last meal, not long before setting out on a hike from which he was never to return. The meal was a simple affair, consisting of a bit of unleavened bread made of einkorn wheat, one of the few domesticated grains used in the Iceman's part of the world at this time, some other plant, possibly an herb or other green, and meat. Oeggl reconstructed the Iceman's last meal from his microscopic analysis of a tiny sample removed from the mummy's transverse colon, the part of the intestine just beyond the stomach. When the Iceman was discovered in 1991, x-rays and CAT-scans of the corpse revealed that his internal organs had shrunken so drastically in the 5,300 years in the glacier that Dr. Dieter Zur Nedden, the radiologist who examined the images, could barely distinguish them. Instead of filling the chest cavity with their billowy white form, the lungs looked like wisps of clouds.

Not until several years after the discovery did the Innsbruck scientists finally cut a hole into the mummy, insert an endoscope, and snip out about .004 ounces from the colon. Dr. Werner Platzer, the University of Innsbruck anatomist then in charge of research on the corpse, gave .0016 ounces milligrams of the material to Oeggl, who had already been studying the rich botanical finds from the site. Oeggl's sample was barely the size of his little fingernail. Under the microscope, he quickly identified the flake-like, semi-digested material that made up the bulk of the sample as einkorn, the most important wheat of the Neolithic, the period of prehistory in which people lived in semi-permanent settlements and survived by agriculture and keeping animals. The discovery of einkorn, which does not occur naturally in Europe, in the Iceman's intestinal tract suggested that he had contact with an agricultural community. The dominance of bran in the sample led Oeggl to believe that the wheat had been finely ground into meal and made into bread, rather than eaten as a porridge, where the grains would have been eaten whole and found in larger pieces in the colon. But the bread would have been little like modern breads. In order to get bread to rise when yeast is added, the wheat grains must contain a high level of gluten, which lends the dough a durable elasticity and therefore holds the pockets of air. Einkorn has low levels of gluten, so the bread made with it was probably hard, somewhat like a cracker, and rather tough on the teeth.

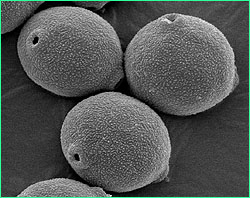

Not everything passing through the Iceman's gut had been swallowed intentionally, or was even desirable. Oeggl also found the eggs of the human whipworm. Many people alive today who do not live in areas with flush toilets also carry the worm, which can cause unpleasant symptoms like stomach ache and diarrhea, or even lead to malnutrition. The scientists have no way of knowing whether the Iceman had any such complaints. The sample also contained many different varieties of pollen, whose strange and beautiful forms Oeggl saw under the electron microscope. Though some peoples are known to eat pollen, Oeggl believed that the quantity in his colon was too small to represent a meal. Instead, the pollen accidentally ended up in the man's stomach because they either had landed in food or water he ingested, or were inhaled and became trapped in saliva which he then swallowed. Scientists had long wondered where the Iceman was coming from and where he was headed, but until the discovery of the pollen inside the corpse, no scientist had any convincing documentation for his last day. But the pollen provided a snapshot of the environment the Iceman was exposed to in the hours before his death.

The pollen of this particular tree was, therefore, one key to understanding the Iceman's last hours. It meant that the Iceman was almost certainly in the valley within half a day of his death. Previously scientists had speculated that the Iceman had died in the late summer, when he was surprised by an early storm while trying to cross the pass. Oeggl readily acknowledges that scientists may never know what prompted the Iceman to leave the relatively hospitable valley with no water or food to speak of (a single sloe berry was found with his remains) and try to cross the mountain at a time of year when several feet of snow easily could have obscured the topography of the steep and rocky Alpine ridge. But his own interest in the Iceman's demise is not yet exhausted. He expects that his meticulous analysis of the botanical and archaeological material recovered from the bottom of the shallow in which the man died will soon reveal more details about the circumstances of the Iceman's death. Brenda Fowler has written on science for The New York Times and is currently writing a book for Random House on the Iceman. Photos (1-3) NOVA/WGBH Educational Foundation; (4) Reprinted by permission of Blackwell Science, Inc.; (5) Botanical Institute of Innsbruck University. Peru Expedition '96 | Unquiet Mummies | Iceman's Last Meal Reading the Remains | Resources | Teacher's Guide Transcripts | Site Map | Ice Mummies Home Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule About NOVA | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Jobs | Search | To print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated November 2000 |

The Iceman on examination table.

The Iceman on examination table.

Preparing the Iceman for a CAT scan.

Preparing the Iceman for a CAT scan.

Wheat spiklets derived from Einkorn grain, stuck to

the Iceman's clothing.

Wheat spiklets derived from Einkorn grain, stuck to

the Iceman's clothing.

Three grains of Ostrya carpinifolia (Hophornbeam)

pollen magnified 1600x.

Three grains of Ostrya carpinifolia (Hophornbeam)

pollen magnified 1600x.