|

|

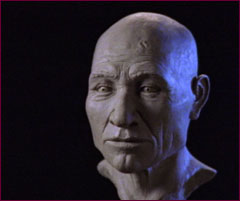

by Jim Chatters Rarely do the ravages of time allow us to gaze directly upon the faces of our remote predecessors. Except for those few who have been frozen in the arctic, pickled in the peat bogs of Northern Europe, or sculpted by their skilled contemporaries, all we have of earlier peoples' visages are their bare, often fragmentary skulls. These skulls, however, hold valuable clues to the physiognomy of the dead. The superstructure on which the soft tissues of the face hung during life, each provides a map of the face it once supported. Facial-reconstruction artists can read this map and produce an approximation of the deceased's appearance. Forensic scientists and others conduct facial approximation for two quite distinct but related purposes: to identify the recently dead so that they can be reunited with their kin, and to give the people of today a glimpse of our forebears as they might have appeared in life. Either way, facial approximation is a closely integrated blending of science and art, the result of a fruitful collaboration between scientists and sculptors. In the NOVA film "Mystery of the First Americans," for example, sculptor Thomas McClelland and I produced Kennewick Man's image, while artist Sharon Long and anthropologist Douglas Owsley created the approximations of the Spirit Cave mummy. The best known facial-approximation team is led by Richard Neave of the University of Manchester, England, who, with John Prag, co-authored the book Making Faces: Using Forensic and Archeological Evidence (Texas A&M University Press, 1997). Neave's team includes not only a medical artist and archeologist, but also specialists in medicine, dentistry, and genetics.

Both schools follow similar basic protocols. Practitioners begin with a skull or, in the case of ancient specimens, a model of a skull, and, at standard locations on its surface, place a set of pegs cut according to average tissue thicknesses. These thicknesses vary according to the ancestry and health of the individual and differ for males and females; people of emaciated, average, or obese condition; and Europeans (or white Americans), Africans (African Americans), or Asians (Japanese). (Experts have not yet developed measurements of average tissue thicknesses for other peoples.) The artist chooses these thicknesses according to information the anthropologist provides based on clues gleaned from the skeleton and any associated clothing and/or preserved soft tissue.

The schools differ most in how they place tissue on the face. The American school relies heavily on the skill of the artist and less on the underlying structure of the skull. The artist first connects tissue-thickness markers with walls of clay pressed against the skull, tapering each bar so that its height is even with the markers at both ends. This creates an open, grid-like pattern. The artist then fills the spaces between the grid lines with clay, and a mannequin-like face begins to take shape. Finally, the artist uses personal experience and input from the scientific members of the team to humanize the face and decide what eye-form and lip characteristics the person should have. In the hands of a skilled artist such as Sharon Long, this approach has proven highly effective, particularly as an aid to identification of the recently dead. Part of the method's effectiveness in the forensic realm lies in the nonspecific appearance that it produces. When the police broadcast faces approximated in this manner, they are likely to stimulate a large number of responses from people missing friends or loved ones. From this large pool of possible identities, the authorities have a good chance of determining the actual identity of the deceased. If the face looked like only one particular individual, the police might get fewer calls and may never identify the subject. Continue: The Gerasimov school's very specific image Does Race Exist? | Meet Kennewick Man Claims for the Remains | The Dating Game | Resources Transcript | Site Map | Mystery of the First Americans Home Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule About NOVA | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Jobs | Search | To print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated November 2000 |

A model of the Kennewick skull (left) and the model

with marker pegs in place (right).

A model of the Kennewick skull (left) and the model

with marker pegs in place (right).

Jim Chatters carefully places clay onto the

burgeoning face of Kennewick Man.

Jim Chatters carefully places clay onto the

burgeoning face of Kennewick Man.