|

|

Part 2 | Back to Part 1 The Gerasimov method aims to produce a very specific image, one as close to that of the deceased as possible. Practitioners of this school, who tend to have an extensive background in osteology and anatomy, begin by closely studying the bones of the face, and observing asymmetries in bone structure and variations in the development of muscle markings. These are clues to the personal characteristics of the dead. Heavily used muscles, for example, leave prominent spurs or ridges in facial bone and show what expressions the person most often held. Next, after placing the tissue thickness markers, the Gerasimov-style artist fashions 18 major muscles from clay and places them on the face according to their standard thickness in human beings. These include the oval sphincters that surround the mouth and eyes, the massive muscles that close the jaws, and the delicate muscles that manipulate the corners of the mouth and wrinkle the brows and nose. Once these are in place, the face begins to take on a human look, albeit a macabre one. Using the muscles now as a secondary superstructure, the artist lays a thin clay "skin" over the face to the height of the tissue markers, taking into account the topography created by the musculature. The resultant face is immediately quite life-like and gives the artist less latitude in crafting the finished face.

Like the American method, the Gerasimov approach has proved useful for forensic identification, but its best application is for approximating the appearance of the long dead. Forensic anthropologists ordinarily rely on this method for recreations of our earlier hominid ancestors. Well-known examples include the Homo erectus created by museum artist John Gurche of the Denver Museum of Natural History and the Neanderthal approximation crafted by Gary Sawyer, a preparator at the American Museum of Natural History. Because we have no artistic standards for how these hominids looked, approximators must produce them with as much scientific rigor as possible.

James C. Chatters is an affiliate research associate professor at Central Washington University and owner of an archeological and paleoecological consulting firm in Richland, Washington. The anthropologist who recovered and first studied Kennewick Man, he is the author of a forthcoming book on how that discovery is changing our image of the first Americans (to be published by Simon and Schuster in early 2001). Does Race Exist? | Meet Kennewick Man Claims for the Remains | The Dating Game | Resources Transcript | Site Map | Mystery of the First Americans Home Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule About NOVA | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Jobs | Search | To print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated November 2000 |

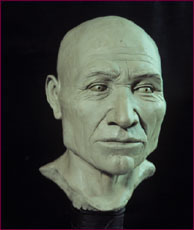

Kennewick Man bearing many of the 18 major muscles

that Gerasimov-style artists fit to a face.

Kennewick Man bearing many of the 18 major muscles

that Gerasimov-style artists fit to a face.

Jim Chatters (partly hidden) and Thomas McClelland

put the finishing touches on their creation.

Jim Chatters (partly hidden) and Thomas McClelland

put the finishing touches on their creation.

Nearly complete, Kennewick Man shows a middle-aged

man in chronic discomfort.

Nearly complete, Kennewick Man shows a middle-aged

man in chronic discomfort.