|

|

|

|

The Dope on Nicotine

by Rochelle Schwartz-Bloom and Gayle Gross de

Núñez

If it weren't for nicotine, people wouldn't smoke tobacco.

Why? Because of the more than 4,000 chemicals in tobacco

smoke, nicotine is the primary one that acts on the brain,

altering people's moods, appetites, and alertness in ways

they find pleasant and beneficial. As the noted tobacco

researcher M.A.H. Russell once wrote, "There is little doubt

that if it were not for the nicotine in tobacco smoke,

people would be little more inclined to smoke than they are

to blow bubbles or to light sparklers."*

Unfortunately, as is widely known, nicotine has a dark side:

It is highly addictive. Once smokers become hooked on it,

they must get their fix of it regularly, sometimes several

dozen times a day. Cigarette smoke contains 43 known

carcinogens, which means that long-term smoking can amount

to a death sentence. In the U.S. alone, 420,000 Americans

die every year from tobacco-related illnesses.

Breaking nicotine addiction is not easy. Each year, nearly

35 million people make a concerted effort to quit smoking.

Sadly, less than 7 percent succeed in abstaining for more

than a year; most start smoking again within days.

So what is nicotine, and how does it insinuate itself into

the smoker's brain and very being? Here, follow the trail

nicotine blazes through the body, from mouth to brain.

Drug

Like cocaine derived from coca leaves and morphine drawn

from opium poppies, the nicotine found in tobacco is a

potent drug. Smokers, and even some scientists, say it

offers certain benefits. One is enhanced performance. One

study found that nonsmokers given doses of nicotine typed

about 5 percent faster than they did without it. To greater

or lesser degrees, users also say nicotine helps them to

maintain concentration, reduce anxiety, relieve pain, and

even dampen their appetites (thus helping in weight

control). Unfortunately, nicotine can also produce

deleterious effects beyond addiction. At high doses, as are

achieved from tobacco products, it can cause high blood

pressure, distress in the respiratory and gastrointestinal

systems, and an increase in susceptibility to seizures and

hypothermia.

Nicotine

First isolated as a chemical compound in 1828, nicotine is a

clear, naturally occurring liquid that turns brown when

burned and smells like tobacco when exposed to air. It is

found in several species of plants, including tobacco and,

perhaps surprisingly, in tomatoes, potatoes, and eggplant

(though in extremely low quantities that are

pharmacologically insignificant for humans). In tobacco, the

highest concentration of nicotine appears in the plant's

topmost leaves. A poisonous alkaloid, nicotine at high

dosages has been used in everything from insecticides to

darts designed to bring down elephants.

Cigarette

As simple as it looks, the cigarette is a highly engineered

nicotine-delivery device. For instance, when tobacco

researchers found that much of the nicotine in a cigarette

wasn't released when burned but rather remained chemically

bound within the tobacco leaf, they began adding substances

such as ammonia to cigarette tobacco to release more

nicotine. Ammonia helps keep nicotine in its basic form,

which is more readily vaporized by the intense heat of the

burning cigarette than the acidic form. Most cigarettes for

sale in the U.S. today contain 10 milligrams or more of

nicotine. By inhaling smoke from a lighted cigarette, the

average smoker takes in one to two milligrams of vaporized

nicotine per cigarette.

Addiction

As early as the 16th century, it was known that

tobacco use led to addiction. In 1527, the Spanish historian

Bartolomé de Las Casas wrote, "I have known Spaniards

on the island of Hispaniola, who were accustomed to taking

[cigars] and who, being reproved and told that this was a

vice, replied that they were not able to stop." Today, we

know that nicotine is the cause of this dependency, and only

a miniscule amount is needed to fuel addiction. Research

suggests that manufacturers would have to cut nicotine

levels in a typical cigarette by 95 percent to forestall its

power to addict.

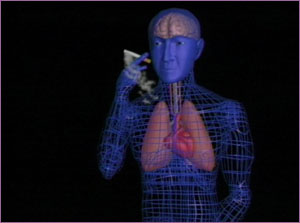

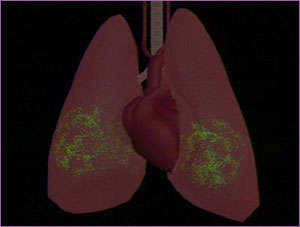

Heart and Lungs

When a smoker puffs on a lighted cigarette, smoke, including

vaporized nicotine, is drawn into the mouth. The skin and

mucosal lining of the mouth absorb some nicotine, but the

remainder flows straight down into the lungs, where it

easily diffuses into the blood vessels lining the lung

walls. The blood vessels carry the nicotine to the heart,

which then pumps it directly to the brain. While most of the

effects a smoker seeks occur in the brain, the heart takes a

hit as well. Studies have shown that a smoker's first

cigarette of the day can increase his or her heart rate by

10 to 20 beats a minute.

Brain

Scientists have found that a smoked substance reaches the

brain more quickly than one swallowed, snorted (such as

cocaine powder), or even injected. Indeed, a nicotine

molecule inhaled in smoke will reach the brain within 10

seconds. The nicotine travels through blood vessels, which

branch out into capillaries within the brain. Capillaries

normally carry nutrients, but they readily accommodate

nicotine molecules as well. Once inside the brain, nicotine,

like most addictive drugs, triggers the release of chemicals

associated with euphoria and pleasure.

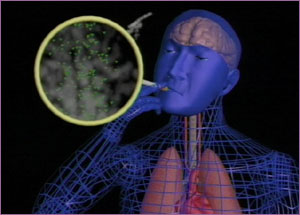

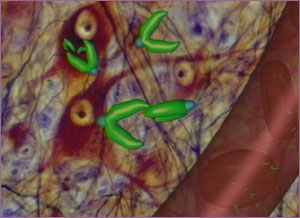

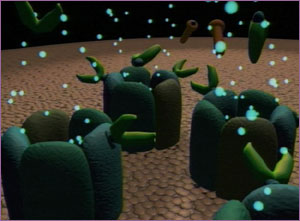

Neurons

Just as it moves rapidly from the lungs into the

bloodstream, nicotine (shown here as green chevrons) also

easily diffuses through capillary walls. It then migrates to

the spaces surrounding neurons—gangly cells that

transmit nerve impulses throughout the nervous system. These

impulses are the basis of our thoughts, feelings, and

moods.

Neurotransmitters

To transmit nerve impulses to its neighbor, a neuron

releases chemical messengers known as neurotransmitters

(shown here as orange bars). Like nicotine molecules, the

neurotransmitters drift into the so-called synaptic space

between neurons, ready to latch onto the receiving neuron

and thus deliver a chemical 'message' that triggers an

electrical impulse.

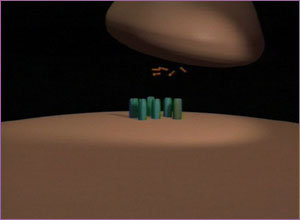

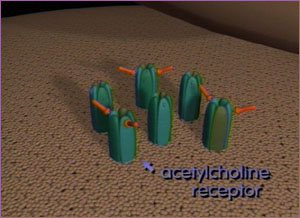

Receptors

The neurotransmitters—in our example, acetylcholine, a

common variety—bind onto receptors (shown here as

green blossoms) on the surface of the recipient neuron. This

opens channels in the cell surface through which enter ions,

or charged atoms, of sodium (see white dots). This generates

a current across the membrane of the receiving cell, which

completes delivery of the 'message.'

Binding

An accomplished mimic, nicotine competes with acetylcholine

to bind to the acetylcholine receptor. It wins and, like the

vanquished chemical, opens ion channels that let sodium ions

into the cell. But there's a lot more nicotine around than

acetylcholine, so a much larger current spreads across the

membrane. This bigger current causes increased electrical

impulses to travel along certain neurons. With repeated

smoking, the neurons adapt to this increased electrical

activity, and the smoker becomes dependent upon the

nicotine.

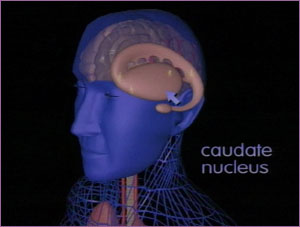

Caudate Nucleus

The caudate nucleus, an area of the brain that controls

voluntary movement, illustrates this adaptation. Without the

nicotine, neurons cannot maintain impulses at the levels

they had previously. As a result, some smokers experience

hand tremors between cigarettes. These "smoker's tremors"

may be hard to see, because a smoker hides them by smoking

another cigarette. The tremors may be a sign of withdrawal,

but they will go away if the smoker gives up smoking for

good.

*M.A.H. Russell, "The Smoking Habit and Its

Classification, The Practitioner 212 (1974):

793.

Rochelle Schwartz-Bloom

|

|

Gayle Gross de Núñez

|

|

Dr. Rochelle D. Schwartz-Bloom is a professor of

pharmacology in the Department of Pharmacology and

Cancer Biology, Duke University Medical Center, and

president of Savantes, a company in Durham, N.C. that

produces science education materials. Dr. Gayle Gross

de Núñez is director of Cajal

Illustration, Chicago, Illinois. The pair coproduced

the video program "Animated Neuroscience and the

Action of Nicotine, Cocaine, and Marijuana in the

Brain," from which this piece was adapted and

expanded. For information on ordering the video,

contact Films for the Humanities & Sciences of

Princeton, N.J. at www.films.com.

|

Anatomy of a Cigarette

|

"Safer" Cigarettes: A History

|

The Dope on Nicotine

|

On Fire

Resources

|

Teacher's Guide

|

Transcript

|

Site Map

|

Search for a Safe Cigarette Home

Search |

Site Map

|

Previously Featured

|

Schedule

|

Feedback |

Teachers |

Shop

Join Us/E-Mail

| About NOVA |

Editor's Picks

|

Watch NOVAs online

|

To print

PBS Online |

NOVA Online |

WGBH

©

| Updated October 2001

|

|

|

|