|

Color photos, old newspapers, the Declaration—we've all seen

materials damaged by long-term exposure to light. But what's

actually happening?

The Declaration of Independence took a lot of abuse in the first

decades of its life. It was rolled and unrolled countless times. It

was tossed in a trunk or stuffed in a linen bag and whisked away

every time the British Army got too near. And for 35 years,

beginning in 1841, it was hung on a wall in the Patent Office in

Washington, D.C., across from a sunny window.

The harm this last insult caused is apparent in a quote from the

Public Ledger in 1876, when the Declaration was taken off

that wall and transported to Philadelphia for the centennial. "Its

aspect is ... faded and time-worn," the Ledger noted on May 8

of that year. "The text is fully legible, but the major part of the

signatures are so pale as to be only dimly discernible in the

strongest light ... and some are wholly invisible, the spaces which

contained them presenting only a blank."

Light is likely not the only reason the Declaration has become so

faded. In the early 1820s, an engraver made a facsimile possibly by

laying a piece of moist paper over the Declaration to soak up some

of the original ink. But light streaming through that Patent Office

window surely further reduced the legibility of our nation's most

precious handwritten document.

And fading of color or ink is only the most obvious injury that

light can cause. In the presence of oxygen or moisture or

temperature changes—or, worst of all, all three—light

can trigger chemical reactions that can degrade the very substance

of the parchment, paper, textile, or other material from which items

of artistic or historical interest are made. In fact, considering

the number of ways that light-induced chemical reactions can wreak

havoc, it's amazing that such items survive for any time at all.

A bad reaction

A bad reaction

Light is paradoxically both our best friend and worst enemy when it

comes to enjoying our most beloved works of cultural heritage. For

it is light that makes visible the rich reds, oranges, and yellows

of a Turner sunset, say, or the deep blues of a Picasso blue-period

painting, or for that matter the dark brown ink gracing the

Declaration. We see those colors because they reflect light back to

our eye from very specific parts of the visible-light portion of the

electromagnetic spectrum.

Unfortunately, what's not reflected is absorbed, and that's where

the trouble starts. Light is energy, and when that absorbed energy

equals or exceeds the so-called activation energy of a molecule in a

dye, pigment, or ink—or in the paper or other material it

graces—the molecule becomes "excited," that is, rendered

available for chemical reactions.

"From a preservation standpoint, that's exactly what you don't

want," says Paul Messier, a Boston-based conservator of photographs

and works of art on paper. "If your object is chemically active, it

means it's interacting with the environment and becoming chemically

altered. Depending on the rate of those interactions, you've got a

recipe for poor preservation and a short life span."

Why? Because any number of things, many of them destructive, can

happen once a molecule gets excited. The extra energy may be

converted to heat (infrared energy) or emitted as light

(phosphorescence or fluorescence). It can break chemical bonds

within the molecule, creating smaller molecules and thereby

weakening the paper or parchment by shortening the long fibers that

make them strong.

Or it can jump to another molecule. In one of the most damaging of

such leaps, the energy transfers to an oxygen molecule, which can

then react with other molecules to jumpstart chemical reactions.

Such oxidation is the bane of museum curators, fine-art owners, and

all of us who want to make things last, whether they are national

treasures like the Declaration or a newspaper clipping of a personal

milestone.

Adding insult to injury

Adding insult to injury

But that's not all. There can be synergistic effects: with higher

temperature and humidity, for example, reactions catalyzed by

electromagnetic radiation can occur more rapidly. And there can be

chain reactions: new substances formed as a result of photochemical

reactions will have enough energy to also react with the original

substance, launching a chain reaction of degradation.

Moreover, some kinds of light are more problematic than others.

Light toward the blue end of the visible spectrum, for example, is

higher frequency—and thus higher energy—than light at

the red end. Thus it packs a greater punch. And ultraviolet

radiation is more energetic still. In fact, it's the most damaging

type of electromagnetic energy in our everyday environment. Even

relatively low-energy infrared radiation can damage materials by

heating them and thereby helping to speed any chemical reactions

already under way.

A 50-watt incandescent light bulb spews out 100

billion billion photons a second, and 95 percent of those are

not helping us to see.

Conservators are concerned not only with frequency but with the

intensity of light hitting artworks or other

valuables—daylight, for instance, is typically brighter or

more intense than artificial light. And then there's exposure time.

As the Declaration shows so clearly, light damage is cumulative.

It's also irreversible (except, as one expert reminded me, in

PhotoShop). Finally, and arguably most unfair of all, chemical

reactions initiated by light can continue even after something is

placed in the dark.

Substance abuse

Substance abuse

The range of our possessions at risk may be wider than you think. It

includes the media used to write, draw, and create photographs, such

as dyes, inks, pigments, varnishes, and oils, as well as the

materials they're used on, like paper, textiles, furniture,

feathers, fur, horn, and bone.

Some of these materials are at greater risk from light damage than

others. Generally speaking, organic materials—those derived

from plants or animals—are more susceptible than inorganic

materials. For instance, natural dyes, which are organic, generally

fade faster than pigments, which are usually comprised of inorganic

minerals. But even organic materials vary in their stability:

materials made of parchment, which is a specially prepared animal

skin, are less vulnerable than, say, silk and wool.

The Star-Spangled Banner is a case in point. Both the dyes and the

wool of our country's most famous flag have been seriously

light-degraded over time. And as expected, the red dye is more faded

than the blue. "The red dyes are more susceptible to fading because

they look red and thus absorb blue, and blue is the higher-energy

light," notes David Erhardt of the Smithsonian Center for Materials

Research and Education, who assisted the flag's conservation

project.

Light housekeeping

Light housekeeping

What to do? Well, for starters, most art on display, whether in a

museum, gallery, or one's own home, is not being enjoyed at any

given time. "It's got all these photons smashing into it, and so for

every minute while it's being illuminated that nobody's looking at

it, that's all wasteful damage," says Steven Weintraub, a

conservator at Art Preservation Services in New York. "There are all

kinds of efficiencies [we can adopt] in terms of UV filters,

reducing the amount of light in general, and shutting off lights

when nobody is around to look at it."

One thing is to remove all those wavelengths we can't see anyway

from the light striking a valued object. A 50-watt incandescent

light bulb spews out 100

billion billion photons a second, and 95 percent of those are

either infrared or ultraviolet radiation, both of which are

invisible to us. All those unnecessary photons slamming into our

watercolor or framed photo at 186,000 miles per second are not

helping us to see; they're only helping to harm the item.

The National Archives filters light on the Declaration to exclude

higher-energy blue wavelengths, for instance. "You're looking

through multiple layers of glass at a very low light level, and that

light has had the harmful portion of the visible spectrum removed

from it as well as the ultraviolet," says Kitty Nicholson, a

conservator who worked on the Charters of Freedom project (see

A Conservative Approach). "So it's a very special light that both enhances the viewers'

visibility and also protects the document."

The National Archives also houses the Declaration in an oxygen-free

encasement filled with the inert gas argon, with carefully

controlled moisture and temperature. Some private institutions have

gone further still, storing vulnerable materials in such oxygen-free

enclosures in temperatures near or below freezing, in the dark. But

that would be pushing it for many cherished objects. As Messier

says, "What good is material that you can never see? It's all about

figuring out the balance."

|

|

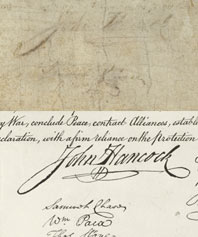

John Hancock's famous signature dramatically reveals how

much the original Declaration (top) has faded versus the

Stone Engraving made in the 1820s.

|

|

|

In the electromagnetic spectrum, the shorter the

wavelength, the higher the energy level of the radiation

and thus the greater the damage inflicted on

light-sensitive materials.

|

|

|

This 19th-century photograph was affixed with a circular

price tag (to left of subject's mouth above) and sold at

an outdoor sale. When the new owner removed the tag, the

overall darkening of the image caused by that brief

exposure to sunlight was all too clear.

|

|

|

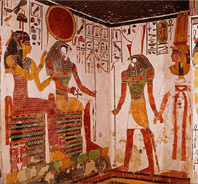

For over 3,000 years, these mural paintings in the tomb

of Nefertari in Egypt's Valley of the Queens were

protected from excessive light, moisture, and

temperature changes, hence their extraordinary

preservation.

|

|

|

Smithsonian conservators photograph the Star-Spangled

Banner during a recent conservation project.

|

|

|