|

|

|

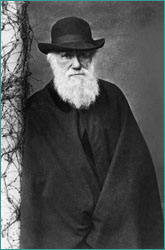

|  The feathers that pestered Darwin

The feathers that pestered Darwin

|

Creature Courtship

by Peter Tyson

"The sight of a feather in a peacock's tail, whenever I gaze at it, makes me

sick!"

—Charles Darwin, in a letter to botanist Asa Gray, April 3, 1860

For most people, the glorious train of the peacock is a joy to behold. But

for Darwin in the years immediately following the 1859 publication of Origin

of Species, in which he laid out his theory of evolution by natural

selection, the peacock's resplendent train amounted to an eyesore.

For the father of evolution, baroque ornamentations like that train and other

seeming extravagances—such as the gaudy tailfin colors of the male guppy,

the saber rattling of the rutting bull elk, and the elaborate bowers of the

bowerbird—seemed to fly in the face of natural selection. How could such

ostentation, so costly to the creature in question in terms of expended time

and energy, benefit the animal and its offspring in the survival of the fittest?

Darwin had

to devise an entirely new theory to explain the peacock's ostentatious

feathers.

Darwin had

to devise an entirely new theory to explain the peacock's ostentatious

feathers.

|

|

The other selection

In

the end, Darwin came up with an entirely new theory to explain the

extraordinary lengths many animals will go to in order to woo a potential mate.

He called it sexual selection. Simply put, sexual selection is the evolutionary

process that favors adaptations that increase an animal's chances of mating.

Darwin identified two kinds. In the first, males compete fiercely with each

other for access to females. This kind favors the evolution of secondary sexual

characters, such as large size and armaments like horns, that enhance a male's

ability to fight. In the second, males compete to win over a female. This

variety favors the evolution of vivid color patterns, intricate courtship

displays, and specialized structures such as plumes and frills, which heighten

a male's attractiveness to the opposite sex.

As we'll see, sexual selection is much more intense among males than among

females. The reason can be summed up in the phrase "sperm is cheap." Since

males bear an inexhaustible supply of sperm, it's in their interest to copulate

with as many females as possible, thereby engendering the most offspring. A

female, by contrast, has a limited cache of eggs. So as not to waste them on

less-than-ideal individuals, it pays for her to be discriminating.

That, in short, is why the feather that made Darwin sick belongs to the peacock

and not the peahen.

So what are some of the enhancements males invest in to court a potential mate?

As the following sampling will suggest, the range is limited only by the

imagination.

Clash of the titans

For males of many species, courtship begins with a thud. Crashing head-on into

one's rival—with painful and sometimes even lethal results—is the order

of the rutting day for many mammals bent on securing sexual favors from nearby

females.

|  Necks scarred from previous

battles, bull elephant seals fight it out on an Antarctic beach.

Necks scarred from previous

battles, bull elephant seals fight it out on an Antarctic beach.

|

One of the most fearsome of such battles occurs every spring among bull

elephant seals. The Sumo wrestlers of the animal world, male elephant seals are

quivering masses of blubber weighing up to 6,600 pounds. When they go at each

other, a pair of bulls rear up, roar loud enough to make the earth shake, and

collide with a thunderous crash. The whites of their bulbous eyes showing, they

gnash at each other's fleshy necks with blunt teeth that leave grievous-looking

wounds and nearby beach water stained crimson with blood. It's a dangerous

game, but the payoff is enormous. On islands off the Pacific coast of

California, for instance, beachmasters may control harems of 100-plus cows.

Males of other species prefer a show of force to force itself. The North

American elk is a good example. Bulls are big-shouldered beasts with majestic

sets of many-tined antlers. Come mating season, they start "bugling" for all

they're worth. This call starts as a bellow, quickly becomes a shrill whistle

or scream, and winds up with a series of grunts. The bull that calls the

longest and most frequently often succeeds in scaring off potential rivals with

his call alone. If challenged, however, he and his adversary walk in parallel

to show each other their "manly" profiles. If this doesn't convince one or the

other to back off, the pair resort to elephant-bull tactics and ram each

other.

A pair of rutting bull elk lock

horns.

A pair of rutting bull elk lock

horns.

|

|

In rare instances, such jousts can cause serious injury or death. But typically

neither is hurt, for the elk's magnificent antlers, which originally did evolve

for fighting and defense, are now largely ornamental. An embellishment to

please the softer sex, the antlers are cast aside at the end of the rutting

season like ornaments after a holiday.

Continue: The meek shall inherit

Photo credits

On the Trail of the Bowerbird |

Are Bowers Art? |

Creature Courtship

Bowerbird Matching Game |

Resources |

Teacher's Guide

Transcript |

Site Map |

Flying Casanovas Home

Search |

Site Map |

Previously Featured |

Schedule |

Feedback |

Teachers |

Shop

Join Us/E-Mail |

About NOVA |

Editor's Picks |

Watch NOVAs online |

To print

PBS Online |

NOVA Online |

WGBH

© | Updated December 2001

|

|

|

|