|

|

|

Creature Courtship

Part 2 | Back to Part 1

The meek shall inherit

While sexual selection has favored the biggest individuals in species like elephant

seals and elk, sometimes tremendous size can work against its owner. Bull

elephant seals, for instance, can reach five times the weight of their mates,

and among the northern subspecies, roughly one in 1,000 cows dies of

suffocation while copulating with such behemoths. Though this death rate is

low, Mother Nature appears to have taken notice and placed a possible check on

the evolutionary trend toward Brobdingnagian. While beachmasters are battling

it out, smaller males are sometimes able to snatch sex from cows apparently

willing to forgo the biggest for the craftiest.

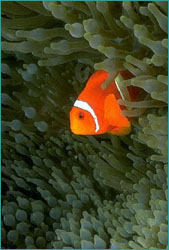

|  Gender-jumper extraordinaire, a clownfish hovers amid the

protective arms of a sea anemone.

Gender-jumper extraordinaire, a clownfish hovers amid the

protective arms of a sea anemone.

|

Biologists have recently identified a similar strategy of trumping the

Schwarzeneggers of one's kind in species a fish found in lakes along Africa's

Great Rift Valley. The fish in question is the shell-brooding cichlid

Lamprologus callipterus. Proportionally, this species boasts the largest

males in the animal kingdom; mature males are up to 30 times the size of their

mates. These comparatively massive males fill their lake-bottom territories

with empty aquatic snail shells. Interested females enter the shells and spawn,

while the giants hover outside, spewing sperm all over the place.

These males might seem to have it made, yet L. callipterus features

another kind of male, one that goes in for brains over brawn. Looking for all

the world like a nonbreeding female, this David swims unmolested into an

occupied shell and, unbeknownst to the Goliath hanging around outside,

fertilizes the female, ensuring a future for his genes.

The male clown fish has evolved an even more ingenious means of getting the

girl: He becomes one. Among clown fish, which form monogamous pairs, the female

is heftier than the male, but if she dies or disappears, the male puts on

weight, changes sex, and bonds with a new male partner.

Looking good

While gender-jumping is common among fish (though it usually happens in the opposite

direction, from female to male), most males in the animal world don't have such a

convenient option. And judging from appearances, many males would just as soon

not have to grapple with others of their gender. These males eschew Darwin's

first kind of sexual selection for his second. On the surface, bright colors,

fancy appendages, and flashy displays may seem a kindler, gentler form of

competition than that evinced among those built for armed combat. But the drive

for success is no less steely.

Striking color combinations are de rigueur among males of many bird species, including this regent bowerbird.

Striking color combinations are de rigueur among males of many bird species, including this regent bowerbird.

|

|

Males in many species attract members of the opposite sex with dazzlingly

colored feathers, skin, or other body parts, which put comparatively drab

females of the same species to shame. Such color dimorphism is particularly

prevalent among birds. Many species show it, from such commonly seen birds as

the cardinal to the elusive quetzal, the most strikingly hued bird in the

Americas. The males of this species have flaming red crests and emerald tail

feathers almost three feet long, neither of which the females possess. That's

because such structures—arguably exemplified by the sexual billboard that is

the peacock's train in full display—are another attribute males have evolved

over the eons to excel in the mating game.

Even the most foppish males seem to realize, however, that beauty is only skin

deep, so they combine appearances with action. The cardinal lures the female

with a series of calls and gifts of tasty sunflower seeds. The quetzal courts

with a painstaking song-and-dance routine. Even the lordly peacock shakes its

brilliant billboard for added effect.

|  Erect and fastidious as a Buckingham Palace guard, a male sage grouse prepares

to parade, his head all but lost in a bravura display of brawn.

Erect and fastidious as a Buckingham Palace guard, a male sage grouse prepares

to parade, his head all but lost in a bravura display of brawn.

|

Holding courtship

Some

of these ritualized courtship displays can be quite involved. On the western

prairies of North America, for instance, male sage grouse congregate on vast

display grounds, where they strut their stuff before females. Mate markets of

this sort are common among birds; ornithologists know them as "leks," which

comes from a Swedish word for play.

Each sage grouse male is a wonder of pumped-up masculinity. Standing tall on

his patch of preferably raised ground, he holds his wings at his sides like

medieval shields, puffs out his robust chest of downy white feathers, throws up

a daunting array of pointed tail feathers, and begins to stomp vigorously on

the ground. (The bird's singular two-step inspired the foot-stomping ceremonial

dances of the Sioux Indians.)

Getting worked up, the grouse then takes a few steps, draws back his head, and

rapidly deflates a pair of scrotal-like air sacs jutting from his chest. The

resulting "plop" can be heard several hundred yards away. At the same time, the

bird briskly rubs his breast feathers against the wings at his side, generating

a swishing sound. When this sequence is finished, he stands still as a statue

for a few moments, then repeats the performance, eager to have nearby hens take

notice.

As with elephant seals, the payoff is tremendous for the cock that impresses

the most hens. On one such display ground, for example, a single male sage

grouse enjoyed fully three fourths of 174 couplings.

One of the most accomplished acrobats in the avian world: the male long-tailed manakin.

One of the most accomplished acrobats in the avian world: the male long-tailed manakin.

|

|

Team work

While

the sage grouse lek has males fervently competing with one another, the lek of

the long-tailed manakin, a diminutive bird found in the rainforests of Costa

Rica, is altogether different. In this lek, two male manakins cooperate

with each other so that the dominant one of the pair can mate with a smitten

female.

The display begins with the two males patiently perched on a horizontal branch

near the ground, calling for females with a distinct toe-le-doe whistle.

When a female lands on the branch, indicating she's ready to be courted, the

two males, which are black with turquoise backs, crimson crowns, and twin tail

feathers as long as their bodies, launch into a prolonged acrobatic display,

whistling their flute-like call all the while. They step daintily and hop

energetically; they somersault and leap-frog; they take turns hovering in the

air.

As the tempo picks up, the males emit a buzzing sound, and the female becomes

more and more excited. At some critical point in the crescendo, the leading

male utters a shrill cry; this is the lesser male's cue to make himself scarce.

Alone at last, the vanquisher performs a brief dance before his prize and then

quickly mounts her.

The long-tailed manakin presents a rigorous test of Darwin's theory of sexual

selection. Not only have males evolved a handsome dress code, including radiant

colors and lengthy tail, but they also dance to beat the band. They'll go on

sometimes for 20 minutes, proving just how fit they are. On top of that, if the

pas de deux is successful, only the lead male gets the spoils. How can the

subordinate male's costly extras and exhausting performance possibly help him

in the survival of the fittest if he knows even before he begins a dance that

he has no chance of mating? Is it all for naught?

Not at all. He learns the ropes, so that when the dominant male dies or becomes

less sprightly with age, his apprentice can take over the lek or perhaps form

his own. Nature has it all figured out.

Peter Tyson is editor in chief of NOVA Online.

Further reading

A Natural History of Sex: The Ecology and Evolution of Sexual Behavior,

by Adrian Forsyth. New York: Scribner's, 1986.

Battle of the Sexes: The Natural History of Sex, by John Sparks. New

York: TV Books, 1999.

The Ant and the Peacock: Altruism and Sexual Selection From Darwin to

Today, by Helena Cronin. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Sexual Strategy, by Tim Halliday. Chicago: University of Chicago Press,

1980.

Photo credits

On the Trail of the Bowerbird |

Are Bowers Art? |

Creature Courtship

Bowerbird Matching Game |

Resources |

Teacher's Guide

Transcript |

Site Map |

Flying Casanovas Home

Search |

Site Map |

Previously Featured |

Schedule |

Feedback |

Teachers |

Shop

Join Us/E-Mail |

About NOVA |

Editor's Picks |

Watch NOVAs online |

To print

PBS Online |

NOVA Online |

WGBH

© | Updated December 2001

|

|

|

|