|

|

|

The U.S. government alone spends $200 million a year on a hunt for a vaccine against AIDS. At the forefront of that search stands Dr. David Baltimore, chairman of the National Institute of Health's AIDS Vaccine Research Committee. Currently president of the California Institute of Technology as well, Baltimore won the 1975 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Betsey Arledge, producer of the NOVA film "Surviving AIDS," interviewed a cautiously optimistic Baltimore on the current state of the search for a vaccine. NOVA: Can you give me a sense of the magnitude of the AIDS epidemic at this time? Baltimore: The AIDS epidemic in this country is a serious issue, but it's not a major public health disaster the way it is abroad. In the world today there are something like 34 million infected people, and more people are being infected every minute. On the scale of any public health issue in the world, this is one of the major ones. There are more people dying of AIDS than of almost any other infectious disease, with tuberculosis and malaria being in the same ballpark. It's a horrendous situation. (See AIDS in Perspective.) NOVA: Do you think we're getting a little complacent in this country? Baltimore: I'm impressed that AIDS remains a very noted disease in the United States. It's noted in the newspapers all the time—what's going on in the world and in the country. There is very complete coverage of how good the drugs are and where the vaccine program stands. I don't think we've allowed it to fall off the radar screen. And we do far more AIDS research than the whole rest of the world; in the vaccine area alone, we do probably 90 percent of the research. NOVA: Can you give me a sense of the amount of effort—not just money, but intellectual effort—that has gone into trying to find a vaccine over the past 10 or 15 years? Baltimore: When H.I.V. was first discovered, the first thing that the then-Secretary of what became the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services said was, "We will have a vaccine in short order." She was wrong about that, but it shows that from the very first moment a vaccine was on people's minds. Indeed, there has been a significant effort to make a vaccine from the very first day. I think people thought it would be simple, because we'd made vaccines for so many different viruses.

At first we thought it might be that many people would be killed by it, and then we began to realize that almost everybody who had the infection was potentially going to be killed by it. That's fundamentally different than other viruses. And that fundamental difference was a red flag. The initial impetus that we'd be able to do it, it's around the corner, was just all wrong. NOVA: So the search for a vaccine has been a real struggle? Baltimore: It's been an enormous struggle, because the obvious things didn't work, and people got very frustrated by that. The next question became: Where do you turn? What's not obvious? What can we do? That involved bringing a whole different level of people into the discussion. Not the ordinary people who make vaccines, but people whose scientific focus is in other areas of immunology, of infectious disease—basic scientists. So it's been a ramping up process to get more and more people involved and thinking about it. Perhaps the most important role of the committee I'm now heading is to galvanize the scientific community to find new routes in thinking about a vaccine, so that maybe we can find a vaccine through some very non-traditional approach. NOVA: An international team of scientists announced recently that they had traced the origin of the AIDS virus to a subspecies of chimpanzee in Africa. If this report is verified, how will it help in the search for a vaccine? Baltimore: In truth, it will not have much effect on the search for a vaccine. However, it tells us a lot about why HIV is so hard to counter. It is not a virus that is native to the human species, and therefore it is continually mutating in an effort to adapt. Most human viruses are well-controlled by the human immune system, because they have evolved with it, and the two opposing forces are in a steady-state. We cannot wait until we and HIV evolve to being comfortable with each other. We must devise a vaccine, effectively short-circuiting the usual process of adaptation. NOVA: Who are the so-called long-term non-progressors, and how do they fit into the search?

There is a balance of three things: whether the virus that those people have is different than the virus other people have; whether their immune system is somehow responding to it differently than other people's immune systems are; and whether their genetics are different. Are they inherently able to fight the virus? Or is it something that's learned and that therefore we could teach other people to do? Continue Search for a Vaccine | See HIV in Action | AIDS in Perspective The Virus Fighters | Fighting Back | Help/Resources Teacher's Guide | Transcript | Site Map | Surviving AIDS Home Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule About NOVA | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Jobs | Search | To print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated October 2000 |

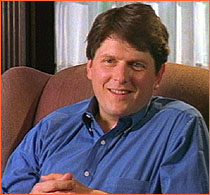

Dr. David Baltimore

Dr. David Baltimore

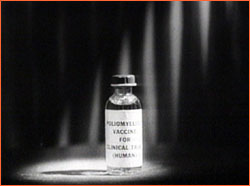

The polio vaccine is effective because, for the most

part, our bodies naturally fight this virus. This is

not the case with HIV.

The polio vaccine is effective because, for the most

part, our bodies naturally fight this virus. This is

not the case with HIV.

Bob Massie is a long-term non-progressor. His immune

system's ability to fight HIV is inspiring a new

approach to fighting AIDS.

Bob Massie is a long-term non-progressor. His immune

system's ability to fight HIV is inspiring a new

approach to fighting AIDS.