|

What's in a Howl?by Fred H. HarringtonProfessor of Ethology Mount Saint Vincent University, Nova Scotia  Ask anyone about wolf vocalizations and the howl invariably springs to mind.

Even though wolves bark, woof, whine, whimper, yelp, growl, snarl and moan a

lot more often than they howl, it is howling that defines the wolf, and

fascinates us. So why do wolves howl?

Ask anyone about wolf vocalizations and the howl invariably springs to mind.

Even though wolves bark, woof, whine, whimper, yelp, growl, snarl and moan a

lot more often than they howl, it is howling that defines the wolf, and

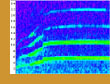

fascinates us. So why do wolves howl?The center of a wolf's universe is its pack, and howling is the glue that keeps the pack together. Some have speculated that howling strengthens the social bonds between packmates; the pack that howls together, stays together. That may be so, but chorus howls can also end with nasty quarrels between packmates. Some members, usually the lowest-ranking, may actually be "punished" for joining in the chorus. Whether howling together actually strengthens social bonds, or just reaffirms them, is unknown. We do know, however, that howling keeps packmates together, physically. Because wolves range over vast areas to find food, they are often separated from one another. Of all their calls, howling is the only one that works over great distances. Its low pitch and long duration are well suited for transmission in forest and across tundra, and unique features of each individual's howl allow wolves to identify each other. Howling is a long distance contact and reunion call; separate a wolf from its pack, and very soon it will begin howling, and howling, and howling...  For the following examples of howling, you can "read" the sound

spectrograph as you listen to the howls. For each spectrograph, the pitch of

the sound is displayed on the vertical axis, so howls low in pitch are nearer

the bottom, and howls high in pitch will be found toward the top. Time is

represented along the horizontal axis, going from left to right, just as you

are now reading this text. A howl that is unmodulated in pitch would appear as

a straight line across the screen. Most howls show some degree of modulation,

so they look like rolling hills or steep ridges leading to or falling away from

plateaus. In addition to its so-called fundamental, or lowest frequency, most

howls have harmonics, which appear as higher and higher bands of sound that run

parallel to the fundamental on the sonagram.

For the following examples of howling, you can "read" the sound

spectrograph as you listen to the howls. For each spectrograph, the pitch of

the sound is displayed on the vertical axis, so howls low in pitch are nearer

the bottom, and howls high in pitch will be found toward the top. Time is

represented along the horizontal axis, going from left to right, just as you

are now reading this text. A howl that is unmodulated in pitch would appear as

a straight line across the screen. Most howls show some degree of modulation,

so they look like rolling hills or steep ridges leading to or falling away from

plateaus. In addition to its so-called fundamental, or lowest frequency, most

howls have harmonics, which appear as higher and higher bands of sound that run

parallel to the fundamental on the sonagram.You'll need one of the free software plugins—RealPlayer or QuickTime to be able to view the sonagram clips of wolf howls below. If you already have the software, choose an appropriate connection speed (RealVideo) or the file size (QuickTime, AVI) to view a clip. A "Lonesome" Howl RealVideo broadband/dialup | QuickTime (3.3MB) | AVI (3.3MB)  The series of adult howls heard here can be classified as "lonesome"

or "lone" howls. Variation in their structure likely indicates who is howling,

and the frequency modulations, particularly the sudden changes in pitch, make

the howls much easier to locate.

The series of adult howls heard here can be classified as "lonesome"

or "lone" howls. Variation in their structure likely indicates who is howling,

and the frequency modulations, particularly the sudden changes in pitch, make

the howls much easier to locate. When a wolf howls, not only can its packmates hear it, but so can any other wolf within range. These other wolves may be members of hostile adjacent packs that are competitors for territory and prey. Howl too close to these strangers, and they may seek you out, chase you, and kill you. In northern Minnesota, where wolves are protected from humans, the primary cause of death for adult wolves is being killed by wolves from other packs. So howling has its costs (running into the opposition) as well as its benefits (getting back with the pack). Consequently, wolves are careful about where and when they howl, and to whom they howl. For example, a wolf that is separated from its pack may return to an abandoned summer rendezvous site and howl for hours, even in response to a stranger nearby. It was accustomed to howling at that site and probably feels relatively confident and secure there. But that same wolf, away from the old home site, will be much more reserved, and if a stranger howls nearby, it may silently and quickly retreat. Younger wolves, however, act differently. Pups, especially those under four months of age, love to howl and will usually reply to any howling they hear, even that of total strangers. This is understandable, since pups haven't yet learned how to identify their older packmates. A Pup Howl RealVideo broadband/dialup | QuickTime (2.3MB) | AVI (2.3MB) The above example of pup howling comes from a three-month-old pup that has just heard an adult howling near the den site. Notice how its howls are shorter in duration and higher in pitch, a consequence of its small overall size and lung capacity. The howls do have the same modulated structure as the adult lonesome howl, and serve the same role as contact calls.  Indiscriminate howling is usually not a dangerous proposition for young pups,

since they tend to be stuck at a rendezvous site that is relatively far from

the neighbors, who likely have pups of their own to raise. More importantly,

replying to an adult that howls often leads to a meal, since packmates

returning with food frequently howl as they near the home site. But as summer

gives way to fall, the benefits of indiscriminate howling decrease.

Indiscriminate howling is usually not a dangerous proposition for young pups,

since they tend to be stuck at a rendezvous site that is relatively far from

the neighbors, who likely have pups of their own to raise. More importantly,

replying to an adult that howls often leads to a meal, since packmates

returning with food frequently howl as they near the home site. But as summer

gives way to fall, the benefits of indiscriminate howling decrease. Once pups start to travel with the pack, they begin to enter less secure surroundings. Their neighbors are also traveling more. Distant howls may belong to strangers, so the risks of howling increase. Besides, by now they have had ample time to learn the voices of their own packmates and are able discriminate friend from foe. By six months of age, pups have become as selective as adult wolves about where, when and to whom they howl. There is one member of the pack who will tend to howl more boldly: the alpha male. The alpha male is the dominant male of the pack, and father of the pups. He is most likely to howl to, and even approach, a stranger—often with confrontation on his mind. One sign of this aggressiveness can be heard in his voice; his howls become lower-pitched and coarser in tone as he approaches a stranger. Lowering the pitch of a vocalization is a nearly universal sign of increasing aggressiveness in mammals, and in wolves it can sound quite impressive. A Confrontational Howl RealVideo broadband/dialup | QuickTime (7.7MB) | AVI (7.7MB)  In the above example, an alpha male howls after approaching a

stranger who had howled close to the rendezvous site. The long, low-pitched and

coarse howls seem designed to scare off the intruder without the need for a

face-to-face confrontation.

In the above example, an alpha male howls after approaching a

stranger who had howled close to the rendezvous site. The long, low-pitched and

coarse howls seem designed to scare off the intruder without the need for a

face-to-face confrontation.This behavior points to the second main purpose of howling: helping to maintain spacing between rival packs. When one pack howls, others nearby may reply. Very quickly, all the wolves know each other's location. By advertising their presence, packs can keep their neighbors at bay and avoid accidentally running into them. But the use of howling in spacing is fraught with difficulties. If one pack howls, all its neighbors (within range, of course) now know its location. What if they choose to keep quiet, sneak up, and attack the howlers? Deliberate attacks by one pack on another have been seen, so there are costs to advertising your location. These risks have to be balanced with benefits. An example of this trade-off is sometimes seen during winter, when packs are traveling nomadically within (or even outside) their territories. A pack sitting on a fresh prey kill is very likely to stake its claim and howl, particularly if a stranger howls nearby. As time passes and the kill is consumed, the wolves become less invested in the site and are less likely to reply. Eventually, they may respond to a stranger's howling by silently moving away. When two packs do meet, their relative size usually decides the outcome. Thus small packs are often quite reluctant to howl and draw attention to themselves, whereas large packs howl readily. But packs can fib to one another about their size. When animals compete, they often engage in behaviors designed to exaggerate their size. Wolves stand tall, raise their hackles, ears and tails, and produce low, menacing howls, all to convince their opponent that a retreat from this "big, bad wolf" is the best option. Thus most confrontations involve a lot of bluff and very little bloodshed. Similarly, packs that are able to exaggerate their numbers are more likely to keep their neighbors at bay. The structure of a pack or chorus howl is well suited to this kind of deception. A Chorus Howl RealVideo broadband/dialup | QuickTime (3.7MB) | AVI (3.7MB) This is a chorus of wolves, made up of at least two adults and two yearlings. Listen to the way this chorus changes. It begins with a single howl, which is relatively simple in structure. After a second or two, a second wolf joins, followed by one or two more before the rest of the pack follows virtually en masse. This accelerating start makes it possible to pick out the first three or four individuals but, after that, too many begin howling at once to count them. Besides, usually only three have howled before the first wolf is ready to howl again, so is the fourth wolf howl in the chorus wolf number four howling for the first time, or wolf number one howling for the second time? Once the whole pack is howling, the sound becomes more and more modulated, changing pitch rapidly in what seems to be chaotic disorder. This continues until the chorus winds down a minute or so later.  Rather than using howls with a single pure tone, wolves howling in a chorus use

wavering or modulated howls. The rapid changes in pitch make it difficult to

follow one individual's howls if several others are howling simultaneously. In

addition, as the sound travels through the environment, trees, ridges, rock

cliffs and valleys reflect and scatter it. As a result, competing packs hear a

very complex mix of both direct sound and echoes. If the howls are modulated

rapidly enough, two wolves may sound like four or more. Indeed, during the

Civil War, General Ulysses S. Grant reported hearing what he took to be a pack

of "not more than 20 wolves" while traveling. A short time later he reached the

pair of wolves that had been making all the noise! This phenomenon, called the

Beau Geste Effect, may introduce enough uncertainty to make size estimates not

only unreliable, but potentially lethal, if a pack underestimates the size of

its rival and approaches.

Rather than using howls with a single pure tone, wolves howling in a chorus use

wavering or modulated howls. The rapid changes in pitch make it difficult to

follow one individual's howls if several others are howling simultaneously. In

addition, as the sound travels through the environment, trees, ridges, rock

cliffs and valleys reflect and scatter it. As a result, competing packs hear a

very complex mix of both direct sound and echoes. If the howls are modulated

rapidly enough, two wolves may sound like four or more. Indeed, during the

Civil War, General Ulysses S. Grant reported hearing what he took to be a pack

of "not more than 20 wolves" while traveling. A short time later he reached the

pair of wolves that had been making all the noise! This phenomenon, called the

Beau Geste Effect, may introduce enough uncertainty to make size estimates not

only unreliable, but potentially lethal, if a pack underestimates the size of

its rival and approaches. So wolves howl to find their companions and keep their neighbors at bay. Popular imagination has long held that they also howl at the moon, but there is no evidence that this is so. Wolves may be more active on moonlit nights, when they can see better, or we may hear them more often on such nights, because we feel more comfortable tramping about in the light of a full moon, but a wolf howling at the moon would be wasting its breath. Photos: (1) © J. McDonald/Visuals Unlimited; (2) © R. Lindholm/Visuals Unlimited; (3) © R. Lindholm/Visuals Unlimited; (4) Animals Animals/© Peter Weimann. What's in a Howl | Ed Bangs | Wolf-Dog Connection Resources | Guide | Transcript | Wolves Home Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule About NOVA | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Jobs | Search | To print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated November 2000 |