|

|

|

Everyone knows the name of the first man on the moon, but what about the last? Eugene Cernan left the final bootprint that may ever appear on the surface of our dusty satellite. Yet Cernan has been heralded for far more than this milestone. He is not only one of the most accomplished of the astronauts—he journeyed into space three times, on Gemini 9, Apollo 10, and Apollo 17—but one of the most eloquent in describing his otherworldly experiences. Below, join him as he lifts off, walks in space, lands and walks on the moon, and reenters Earth's atmosphere. From the book The Last Man on the Moon. Copyright 1999 by Eugene Cernan and Don Davis. Reprinted with permission of St. Martin's Press, LLC, New York, NY

The countdown reached ten seconds and I could almost hear an invisible crescendo of stirring background music. Anchors aweigh! Five, four, three, two, one . . . and we had ignition! To this day, I don't really know what I expected. My training told me it might be like a catapult launch on a carrier, swift and violent, but Tom [Stafford, commander of Gemini 9] and others who had flown said it would be, well, different, although they couldn't explain how. Just . . . different. On television, everyone saw clouds of flame and smoke boil from the bottom of the Titan, but inside the spacecraft, the instrument panel had come alive. Dials were jumping, lights shone brightly, the computers spat out strings of numbers, and ground controllers spoke rapidly. There was a noticeable shudder as the Titan's fuel spewed into the tanks and ignited, then I felt a faraway bump as the bolts holding the rocket to the pad blew away, and something amazing happened ten stories under my back at 6:38 on a sunny Florida morning. I sensed movement, a feeling of slow pulsation, and then heard a low, grinding rumble as that big rocket ship started to lift away from Earth in agonizingly slow motion. The Titan, once a silent, sleeping giant, was now fully awake and flexing its muscles, ready to romp toward an incredible 430,000 pounds of thrust and haul ass out of there like a favorite leaving the gate at the Kentucky Derby. The initial slow ascent turned into a sudden vault of speed, and we were away. The sides of the rocket were washed by a glistening sun as the Titan pushed off, gaining altitude and speed by the instant. In Mission Control, Flight Director Gene Kranz listened carefully as his controllers reported, station by station. "Good. Excellent. Everything is green and go!" By then, the rocket was galloping out across the Atlantic and the forces of gravity stacked like bricks on my chest. My heart was beating a mile a minute and I gritted my teeth. A glance showed that Tom was gritting his, too. "We're on our way." At least Tom could speak. On the other side of the spacecraft, his rookie pilot could say nothing at all. As I worked at my assigned tasks, I simultaneously felt and saw things I had never imagined. God, if only I were a poet.

When the hatch stood open, I barely pushed against the floor of the spacecraft and my suit unfolded from the seated position. I grabbed the edges of the hatch and climbed out of my hole until I stood on my seat. Half my body stuck out of Gemini 9, and I rode along like a sightseeing bum on a boxcar, waiting for the sun to come up over California. And, oh, my God, what a sight. Nothing had prepared me for the immense sensual overload. I had poked my head inside a kaleidoscope, where shapes and colors shifted a thousand times a second. "Hallelujah!" was the best I could muster. "Boy, it sure is beautiful out here." I did not have the words to match the scene. No one does. Outer space was dead and empty while simultaneously alive and vibrant. Since we were rushing along at about 18,000 miles an hour, we hurried the dawn. Pure darkness gave way to a ghostly mist-gray, then a thin, pale band of fragile blue appeared along the broad and curving horizon. It changed quickly to a deeper hue over narrow bands of gold, and then the sun, a brilliant disk, jumped up to ignite a sky where night had ruled only a moment before, and its rays slowly erased the darkness on our planet below. Blue water shimmered on both sides of the Baja peninsula beneath California and the deserts of our Southwest shone like polished brass. An ivory lacework of thin, soft clouds stretched for miles. This was like sitting on God's front porch. The heavenly canopy surrounding me was still soot black, but stars could no longer be seen, and the subfreezing cold of the space night yielded to new, broiling hot temperatures. We crossed the coast of California in the full flare of the morning sun, and in a single glance, I could see from San Francisco to halfway across Mexico.

As we slapped into molecules of air, the G-forces built rapidly and my eyes were drawn to the new and unparalleled scene forming beyond our window. A streak of orange flashed past, a skinny lightning bolt that instantly vanished into space. From the other side, a green streak zipped by, then, all around us, brilliant stripes of blue, red, and purple came faster and faster as the blunt end of Gemini 9 collided with the thick atmosphere. Traveling at thousands of miles per hour, the friction of the spacecraft crashing through air created a ball of fire, and heat built inside the cabin. The last words we heard before the radio was silenced were: "Have a good trip home." The computer gave us reentry readings and Tom rolled the off-center spacecraft slightly, 50° to the left, then 38° back to the right, taking numerical aim at the targeted landing zone some 350 miles east of Cape Kennedy, half a world away. That slight corkscrewing movement made the long tongues of flame trailing along behind us like sleek wings swirl and curve over each other, brightly fluorescent in the darkness. Shades of oranges and yellows and glowing reds, shining blues and greens intermingled, coiling in a colorful spiral. Our movie camera photographed the fire streaking away from the heat shield to join the tail of flame. Individual sparks would land for an instant on the nose, stick and glow like playful imps, then be swept away by the gigantic wind created by our passing. It was goodbye to darkness and hello to a light show that would put a rock concert to shame. Then the fire completely enveloped us, the blaze coating the spacecraft and spreading from the burning heat shield all the way back beyond the nose, merging at some unseen point far behind. The forces of gravity climbed steadily, past four Gs, past five, and going up as we burned our way through the wall of silence. It felt as if the Jolly Green Giant was stomping on my chest. Radio waves could not pierce the blazing turbulence. Fire was all I could see, and the radio would be dead for at least four minutes while we sailed through this 3,000-degree hell. It is claimed that there are no atheists in foxholes. I know there are none in spacecraft plunging back to Earth in a ball of fire, and I said a quick prayer. Continue: Flying to the Moon (Apollo 10) Explore the Moon | Lunar Puzzlers | Last Man on the Moon Hear the Space Pioneers | Origins | Resources Transcript | Site Map | To the Moon Home Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule About NOVA | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Jobs | Search | To print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated November 2000 |

Astronaut Eugene Cernan

Astronaut Eugene Cernan

Gemini 9 blasts off from Cape Kennedy on June 3,

1966.

Gemini 9 blasts off from Cape Kennedy on June 3,

1966.

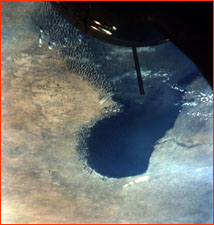

An astronaut's-eye view of Africa's Lake Chad, taken

from the Gemini 9 spacecraft.

An astronaut's-eye view of Africa's Lake Chad, taken

from the Gemini 9 spacecraft.

Shortly after touchdown, Gene Cernan (left) and Tom

Stafford congratulate each other aboard the USS Wasp.

Shortly after touchdown, Gene Cernan (left) and Tom

Stafford congratulate each other aboard the USS Wasp.