|

|

|

|

|

Mapping the Treasuresby Colin Clement

As with any archaeological site, the plotting of a detailed and accurate map of the mass of ruins is a necessary first step to figuring out what one has actually found. And in this case, the very nature of the underwater site precluded the possibility of returning day after day in whatever

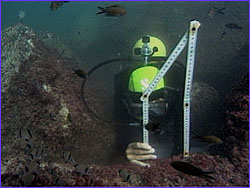

The team began by establishing a fixed position Electronic Distance Measurement station (EDM)—effectively, an electronic theodolite—on the shore. This is used to "spot" the underwater blocks, which are indicated by a reflector mounted upon a floating mast. The mast is connected to a lead line that in turn is placed against the four corners of the submerged block and held in position by a diver. Another diver, on the surface, ensures that the correct tension is maintained and that the floating mast doesn't move too much. This technique was accurate to between 4 and 12 inches, depending on sea conditions, and was the sole option given the need to relate the underwater site to other archaeological sites on land in Alexandria.

This rapid, 24-hour turnaround in what began as an experimental method has contributed enormously to the progress of the excavation. It also seems clear that this technique can now be applied to other underwater sites around the world. In theory, it doesn't matter how far underwater the

Two other methods are used to map the site: triangulation, using several permanently fixed underwater reference markers; and the Global Positioning System (GPS). The expedition was fortunate enough to be loaned a state-of-the-art GPS (accurate to within one centimeter, or 0.4 inches) by the Swiss company Leica. When this GPS device is mounted on a rubber dinghy and combined with a sonar device, it gives an exact reading of the contours of the seabed. This information is particularly relevant in analyzing the formation of the site, given the strong possibility that part of what is now the seabed was dry land in antiquity. The mass of data accumulated over almost ten months of diving has all gone into a giant computerized database. Three types of information on each registered block—written, drawn, photo and/or film—has been recorded and can be combined to produce either on-screen or hard copy identification sheets. The addition of extensive photography and video film, which can be paused and rewound, makes the site much easier to study, since the blocks themselves are underwater. Furthermore, a simple click on any individual

The creation of the block identification sheets has made it possible to define the type of blocks discovered and to develop a terminology. In architecture, terminology is linked to the function of a block in the construction—a lintel is only so-called because it serves as a lintel—but here we are dealing with an essentially unknown construction or constructions and the majority of elements are lying completely out of context. The new terminology that is being established must ignore the idea of function and look, instead, at four criteria: form, dimension, volume, and decoration. Obviously, this very activity brings blocks together into identifiable groups and is the first step on the road to interpretation. What the database has already made clear is that the site is made up mostly of materials that have been recycled or pillaged, in the time-honored Egyptian fashion, from pre-existing structures in the Nile Delta and at Heliopolis. There are clear signs of the application of Graeco-Macedonian technological savoir faire to thoroughly Egyptian architectural materials (more than 90 percent of the blocks are of granite), and this juxtaposition, in itself, will throw light upon the style and method of construction of the Pharos lighthouse. In other words, it is likely that the Pharos was not built in purely Greek style, because the Greeks had no experience of building with granite and would have had to use local labor. On the other hand, the Pharos would not have been purely Egyptian, because the Greeks

Clearly, the architectural analysis of the Pharos site is still in its infancy and presents a formidable challenge. The only blocks that can be dated even approximately are those bearing decoration—moldings, inscriptions, statuary, etc.—and there are relatively few of these. The fact that the majority of the material has been recycled also presents a challenge. Any masons' marks or traces of construction techniques could either be from the original structure or from the building of the Pharos itself. In fact, before any architectural analysis can be definitively broached, the long, painstaking, and at times tedious accumulation of data must be completed. The 2,110 blocks recorded as of the end of June 1997 may comprise the totality of the upper layers, but until access can be gained to what lies beneath, the study of the site will not be complete. (It is anyone's guess how many more artifacts have yet to be uncovered.) At the same time, there is a need to polish and fine-tune the established database. However, the aim of the game remains to produce hand-drawn and computer-generated reconstitutions of architectural elements that now lie in pieces on the bed of the Mediterranean Sea and to advance a clear hypothesis as to the spatial arrangement of the site. Given enough time and resources, this is indeed possible. Colin Clement, originally from Edinburgh, Scotland, is a writer and translator who has lived in Alexandria for the past eight years. Since 1994 he has been working closely with the Centre d'Etudes Alexandrines (Center for Alexandrian Studies) researching, compiling and editing reports and closely following the various archaeological excavations of the Centre. Mapping the Treasures | Empereur | Unforgettable Moments Seven Wonders | Resources | Guide | Transcript | Treasures Home Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule About NOVA | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Jobs | Search | To print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated November 2000 |

||||||||||||||||||||