|

|

|

(back to Life on a Submarine) Every 14 to 18 months, we would make a patrol in the Northern Pacific. We'd leave Pearl Harbor, steam on the surface to the Aleutian Islands, top off the fuel and load up with fresh food at the Navy port in Adak, Alaska, then leave. Once we got on station, we submerged, and unless we had an emergency, we would stay on station, totally submerged, for 60 days. You get into a routine and just grow accustomed to it. The hardest thing I had to cope with was the cold. Up there it is always cold, and since energy on a diesel submarine was very critical because of the power, we couldn't run our heaters. So we would just be freezing most of the time. And there were absolutely no showers. Nobody took a full, hot shower except the mess cooks. You'd just take the old douche from the sink and wash your underarms. When you made the northern runs, it wasn't too bad as far as body odor. Of course, everybody pretty well kept that under control. If anybody didn't, we took care of them.

When you're snorkeling submerged, you're really running blind, since the noise makes your sonar essentially ineffective. It is one of the most dangerous periods, so you always have a periscope watch. That way you can at least keep an eye on what is happening on the surface so you don't happen to run into anything. But you never know even in charted waters when you could hit something. We did have a collision once. It could have been a whale, or it could have been an obstacle such as land. Our depth chart could have had a slight error. The collision damaged our sonar dome, but fortunately it didn't puncture the hull of the boat. But we were charging batteries at the time and the lights went out and a spark started a fire in one of the main rheostats in the maneuvering room. That was pretty scary, but we were able to get the fire out and go off station and surface. When the collision alarm goes off, everybody has a certain job to do. That's why it is important that you know other jobs in a compartment, because one of the first things you do is seal off the watertight doors in each compartment. Say you're in the forward torpedo room. Well, there might not be a torpedoman up there when something like that happens. So any crew mates that happen to be up there should be familiar enough with the compartment to handle any emergency situation. —Dennis Splane was an Electrician's Mate, 2nd Class when he left the USS Tunny (SSG-282), a diesel sub refitted to carry Regulus missiles, after serving from 1958 to 1961. He lives in Grapevine, Texas. Continue: Tippy D'Auria

See Inside a Submarine | Can I Borrow Your Sub? Sounds Underwater | Life on a Submarine Resources | Transcript | Site Map | Submarines Home Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule | About NOVA Watch NOVAs online | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Search | To Print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated May 2002 |

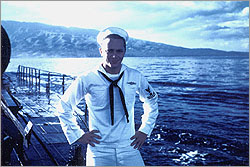

Dennis Splane

Dennis Splane

Dennis Splane in 1961.

Dennis Splane in 1961.