|

|

|

by Peter Tyson In August 1993, when the USS Pargo, a Sturgeon-class attack submarine, went to sea with five civilian scientists aboard, George Newton smiled. It had been the end of a long journey for him. Newton is Chairman of the U.S. Arctic Research Commission and a 25-year Navy submarine veteran who served under the legendary Admiral Hyman Rickover. Ever since he'd first deployed to the Arctic aboard a Navy sub in 1971, Newton had hoped one day to get Navy submarines to take civilian scientists to the Arctic, a place notoriously difficult to study. The idea remained germinal until the late 1980s, when the Soviet threat dissipated like smoke and the U.S. government began seeking new, "dual" uses of its military assets. That's when Newton swung into action. "I got thrown out of a lot of offices, albeit politely," Newton recalls of his seven-year struggle to convince the Navy to give his brainchild a whirl. The idea of highly classified "ships of the line" gallivanting around the Arctic at the whim of men in white lab coats—one can almost feel the bristles going up on necks of Navy admirals. But with the help of civilian scientists, among them Dr. Gary Brass of the University of Miami and the late Dr. Marcus Langseth, a geologist at Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Newton pressed on. In the end, one of the very brass hats who had once ushered him to the door opened that door for negotiation, and by late 1992 the Navy had accepted the proposal.

The SCICEX cruises were not the first time an American nuclear submarine had traveled under the Arctic ice. That distinction rests with the USS Nautilus, the country's first nuclear sub, which did so in 1958. Nor was the 1993 Pargo jaunt the first time the Navy had lent out its equipment to scientists. In the early 1990s, the Navy began letting civilian researchers borrow its $15 billion underwater hydrophone system, which was formerly used to eavesdrop on Soviet subs. Geologists listened in on undersea eruptions and earthquakes, while biologists tracked the migrations of singing whales.

The Navy has even performed science before using its nuclear fleet. But the advent of SCICEX marked the first time they had earmarked active nuclear submarines for dedicated science cruises. Global warning Scientists believe there is an urgent need to study the Arctic Ocean. Since 1990, its waters have warmed by as much as 2°F, a significant increase for an entire ocean (albeit the world's smallest). The rise began after balmier water from the Atlantic began muscling its way into the northern ocean. As a result of the warming, the permanent pack ice has retreated some 100 miles north, and in summer it has thinned by about a foot to just six feet. The snow-white Arctic reflects sunlight back into space, providing a vital climatic counterbalance to the tropics' heat. If the ice melted, leaving a wine-dark sea to absorb the sun's rays, it could accelerate global warming. Continue

See Inside a Submarine | Can I Borrow Your Sub? Sounds Underwater | Life on a Submarine Resources | Transcript | Site Map | Submarines Home Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule | About NOVA Watch NOVAs online | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Search | To Print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated May 2002 |

Greg Kurras, a member of the civilian scientific team

that rode the nuclear attack submarine USS

Hawkbill into the Arctic in August 1998, poses

at the North Pole.

Greg Kurras, a member of the civilian scientific team

that rode the nuclear attack submarine USS

Hawkbill into the Arctic in August 1998, poses

at the North Pole.

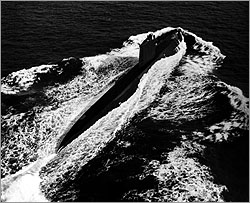

In 1958, the USS Nautilus,

America's first nuclear-powered submarine, became the

first sub to travel under the Arctic icecap.

In 1958, the USS Nautilus,

America's first nuclear-powered submarine, became the

first sub to travel under the Arctic icecap.

For years, the Navy has lent civilians its miniature

nuclear sub, the NR-1, to conduct everything from

oceanographic studies to searches for ancient

shipwrecks.

For years, the Navy has lent civilians its miniature

nuclear sub, the NR-1, to conduct everything from

oceanographic studies to searches for ancient

shipwrecks.