In Defense of Pluto

- By David Levin

- Posted 01.01.10

- NOVA

Planetary scientist Alan Stern, director of NASA's New Horizons mission to Pluto, makes a case for why Pluto deserves to be categorized as a planet. Stern says that Pluto not only meets what astronomers call the "geophysical planetary definition" but also passes the "Star Trek test."

Transcript

In Defense of Pluto

Posted January 1, 2010

DAVID LEVIN: You're listening to a NOVA podcast. I'm David Levin.

After Pluto was discovered in 1930, it enjoyed the title of planet for more than 75 years, but in 2006 that all changed. At a meeting in Prague, the International Astronomical Union, or IAU, adopted a new definition for planethood, leaving the solar system with only eight planets.

But not everyone agrees with their decision. Alan Stern is especially unhappy about it. He's a planetary scientist who's been studying Pluto for years. He talked to us about Pluto's demotion and why he thinks it should be back on the list of planets.

DAVID LEVIN: Alan, thanks for speaking with us.

ALAN STERN: Well thanks very much for inviting me.

DAVID LEVIN: So I understand that you're not exactly thrilled with the IAU's decision.

ALAN STERN: I think it was badly misguided, and the IAU now, I think, deeply regrets what it did. It was a public relations disaster for the organization, and it's quite clear that more and more people are coming to just ignore what they did. Some people call it the irrelevant astronomical union.

DAVID LEVIN: So how do you think we should define a planet?

ALAN STERN: The definition that I like, and that a lot of planetary astronomers like, is called the geophysical planetary definition. It asks only two questions, and if it passes both tests, it's a planet. First question is it in space? Pluto passes that test pretty easily. Secondly, is it large enough for gravity to have overwhelmed material strength so that it will flow into a sphere, the shape of a sphere? And Pluto also passes that test, in fact by a large margin, and so that's how we differentiate between small rocky shards and big things that act like planets.

DAVID LEVIN: So once you get past a certain size, an object has enough gravity to start forming into a planet-like shape on its own?

ALAN STERN: Correct. And then there's a third criteria that says it's not so big and so massive that it actually ignites in nuclear fusion because we call those objects stars. So any object that's never been a star but that's large enough to be rounded under self-gravity and is in space qualifies as a planet.

DAVID LEVIN: So you mention in the NOVA program that there's an even simpler criteria you like to use. I think you call it the Star Trek test.

ALAN STERN: Yeah, the Star Trek test is really simple. When Captain Kirk and the starship crew shows up at any given world and turns on the viewfinder, the audience knows immediately on looking at the object if it's a planet or a star or simply an asteroid or small comet or something. They don't have to do any math. They don't have to catalog every other object in the solar system and determine where the orbit stabilities are, right? You just look at it. This is what I call the Star Trek test. People know a planet when they see one, and I think that's a pretty darn good test, in fact, for planet hood.

DAVID LEVIN: So why do you think people have reacted so strongly to Pluto's demotion?

ALAN STERN: Well I think I'd say the same thing that our President might say today about another matter is that change is hard. This really is about change. People grew up thinking there were nine planets, and when they were presented with the fact that our own solar system might not have nine but perhaps closer to nine hundred, and that most of those planets, being dwarf planets, are not like the Earth at all, it was jarring to many people including many of my colleagues in planetary science and astronomy.

Unfortunately the data is the data, and you can put on blinders, but this is simply what the universe presents us with.

DAVID LEVIN: I know some of your critics have said that we can't possibly allow that many objects in the solar system to be called planets because, from an educational standpoint, no one would be able to remember all those names.

ALAN STERN: I just think it's patently absurd for scientists to categorize objects on the basis of the numbers of objects that they can remember. For example, on the Earth we don't have eight rivers, we have countless rivers, and all that we require school kids to know is that there are a few big ones like the Amazon whose name you should remember and that there are a really large number of rivers. And then we teach them how to recognize a river when they see one, and that's all you have to know. And it's very similar. Now we know there are lots of planets, and it's pointless to try to memorize all their names, just like the stars.

DAVID LEVIN: So you're the principle investigator for a NASA spacecraft called New Horizons that's on its way to Pluto right now. Could you tell us a little bit about what you hope to learn from that mission?

ALAN STERN: Sure, sure. New Horizons is just past halfway to Pluto to arrive in the summer of 2015, and its job is to make the first reconnaissance of Pluto and its satellite system to map the surfaces of those worlds, to map their surface composition and temperatures, to assay the atmospheric structure and composition, and give us, for the first time, an understanding of this third class of planet, not a terrestrial world like Venus, Mercury, Earth and Mars, not a gas giant like Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune, but the most populous class of planet in our solar system, the ice dwarfs.

DAVID LEVIN: And that's all beyond the reach of existing telescopes, like Hubble?

ALAN STERN: Right, even with Hubble space telescope, Pluto's just a smudgy little dot with the barest of surface features that are resolvable.

DAVID LEVIN: So once we have real data on what Pluto does look like, are you hoping that'll restore its title as a planet?

ALAN STERN: I think when people see Pluto revealed by New Horizons, its satellite system, its complex surface, its atmosphere, I think they'll have a hard time saying "That's not a planet" because it obviously will be, and I think most people are already coming to that opinion anyway, but I think that's really going to drive it home viscerally.

DAVID LEVIN: Sort of the Star Trek Test in action.

ALAN STERN: It will be the Star Trek test in action, well put.

DAVID LEVIN: Well Alan, thanks again for speaking with us.

ALAN STERN: Thanks for inviting me on.

Credits

Audio

- Produced by

- David Levin

Image

- (Alan Stern)

- Courtesy Alan Stern

Related Links

-

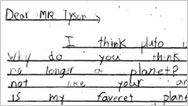

Hate Mail From Third Graders

See what some outraged but loving kids had to say to astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson about "demoting" Pluto.

-

The Pluto Files

Take a cross-country journey with Neil deGrasse Tyson to explore the rise and fall of America's favorite planet.

-

My Dad Discovered Pluto

How did Clyde Tombaugh go from baling hay to finding Pluto? See family photos and hear his son Alden reflect.

-

What's Your Favorite Planet?

Listen in as 11 planetary scientists make pitches for the "best" planet, then vote yourself.

You need the Flash Player plug-in to view this content.