|

|

|

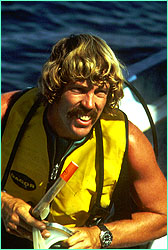

Dr. Peter Klimley is a man who has held his breath and dived down 100 feet to hand-tag hammerhead sharks with a dart gun. He has even dressed up as a killer whale, complete with towering black dorsal fin, to gauge the reaction of lemon sharks (one tried to bite him). An associate research behaviorist at the Bodega Marine Laboratory, University of California at Davis, Klimley has studied scalloped hammerheads at an underwater mountain, or seamount, known as El Baho Espiritu Santo in the Gulf of California off Mexico for two decades. If you want to know something about hammerheads, you ask Pete Klimley. We did, and we did. Here's the result.

Klimley: Oh, it's great. The first time I did it the water was kind of murky. I could barely see them and then suddenly I was smack in the middle of them. I was close enough to reach out and touch their skin. At that time, sharks were all thought to be man-eaters, so diving down to see them was against the grain, very iconoclastic. I don't know why people thought that sharks, most of which are about our length, would be eating us, but that's what they thought. And there they were all around me, and they were beautiful. The sun was reflecting off their sides, and they were kind of rippling as they moved. There have been times since at the seamount when I wouldn't even have to dive. They'd be swimming so close to the surface that all I had to do was tread water with my feet down and I'd be touching them. I'd be filming them and all their elaborate behaviors—such as the reverse flip with a full twist that a female will use as a signal to other females to move away, that she is the dominant female—and they'd be looking at me. I'd be thinking, "God, they're intelligent. What do they think of me?"

Klimley: Yes. The U.S. Navy, in fact, once considered the hammerhead the third most dangerous species after the great white and the tiger shark. (There are nine species of hammerheads, but the Navy was considering only the largest ones.) Today, the bad guys are the white, bull, and tiger sharks. The bull and the white do occasionally take people whole, though the white shark tends to spit them out. Being a cold-water species, it forages preferentially for fatty foods, I believe. So it spits out birds and sea otters and humans and just eats seals and whales. Hammerheads are among the majority of sharks whose attacks on people, if they happen at all, are defensive in nature. Almost all sharks will show an aggressive display if cornered, as will most animals. If you corner a raccoon or a cat, it will attack. The consequence of such defensive attacks in the marine environment have frightened people. Now, the hammerhead has that really unusual head. Everybody remembers that head. So, when there is one of these defensive bites, victims can identify the shark quite easily. Whereas if it's just a gray-colored reef shark, there are lots of different species and they all look alike. NOVA: Have you ever felt in danger while working with hammerheads in the wild? Klimley: I'm a real enemy of that whole mindset of sharks and danger. The majority of sharks that you'd encounter—blue sharks, silky sharks, pelagic whitetip sharks—all these are not dangerous. What happens is filmmakers go out there and throw a lot of bait in the water, and then they see this very unusual hysteria of sharks biting at anything. It would be the same if you threw meat to a pack of dogs that hadn't eaten for a long period and filmed it. It's unfortunate that cinematography has given sharks this narrow image—it's the five percent, not the 95 percent. I've tried in my life to fight against that mindset.

Klimley: I don't ever tell anybody to become a shark researcher. Better to become interested in some biological facet or discipline. You want to understand how animals behave or how do they navigate or how do they communicate with one another. Then you pick your species. However, I must admit that I started studying sharks because I thought they were scary and little was known about them. I loved animal behavior—Conrad Lorenz, Desmond Morris—and I wanted to be like Diane Fosse, who I saw in "National Geographic" among mountain gorillas. I wanted to go among the sharks. Few had done it. Then there was the great white shark. Nobody knew anything about it, or very little. There was something about studying your possible predator that intrigued me, so I went up to Northern California and started to study the white shark. The feeling that sharks are bigger and badder than we are and live in an environment that we're not comfortable in gives you a kind of morbid or forbidden fascination with them. Continue: What do you think has made you a successful shark researcher? Cocos Island | Sharkmasters | World of Sharks | Dispatches E-mail | Resources | Site Map | Sharks Home Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule | About NOVA Watch NOVAs online | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Search | To Print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated June 2002 |

Pete Klimley

Pete Klimley

Klimley makes a breath-hold dive among hammerheads.

Klimley makes a breath-hold dive among hammerheads.

Scalloped hammerheads on the move.

Scalloped hammerheads on the move.

Klimley often takes an underwater

video camera with him on dives.

Klimley often takes an underwater

video camera with him on dives.