|

|

|

by Peter Tyson Jacques Cousteau deemed it "the most beautiful island in the world." Michael Crichton wrote "Jurassic Park" with it in mind. Robert Louis Stevenson may have based his classic "Treasure Island" on it. Cocos Island, 300 miles off the coast of Costa Rica, is legendary for its natural and man-made treasures. The largest uninhabited island in the world, this 10-square-mile tip of an ancient volcano is the only isle in the eastern Pacific that bears rainforest. From the precipitous cliffs towering over the craggy shoreline to the 2,079-foot summit of Mt. Iglesias, the island's highest peak, the luxuriant bed of jungle is riven only by scores of sparkling waterfalls that tumble out of the heights.

Cocos' story begins in 1526, when the Spanish pilot Johan Cabeças first discovered the island. Sixteen years later, it appeared for the first time on a French map of the Americas, labeled as Ile de Coques (literally "Nutshell Island" or simply "Shell Island"). The Spanish apparently misunderstood the French name and called it Isla del Cocos ("Island of the Coconuts"), which proved apt enough. "`Tis thick set with Coco-nut Trees, which flourish here very finely," wrote Lionel Wafer, a surgeon who penned one of the earliest descriptions of this island after a visit in the late 1600s. So abundant were coconuts that Wafer's companions made a bit too merry with the milk one afternoon, drinking 20 gallons at a sitting: "[T]hat sort of Liquor had so chill'd and benumb'd their Nerves, that they could neither go nor stand; nor could they return on board the Ship, without the Help of those who had not been Partakers in the Frolick . . . ."

The Golden Age of treasure-burying on the island took place in just a few years on either side of 1820. It all began in 1818, when Captain Bennett Graham, a distinguished British naval officer put in charge of a coastal survey in the South Pacific aboard the H.M.S. Devonshire, threw up his mission for a life of piracy. He was eventually caught and executed along with his officers, the remainder of his crew being sent to a penal colony in Tasmania. Twenty years later, one of the crew, a woman named Mary Welch, was released from prison bearing a remarkable tale. She claimed to have witnessed the burial of Graham's fortune—350 tons of gold bullion stolen from Spanish galleons. (A recent estimate put the treasure's present-day value at $160 million). Moreover, she had a chart with compass bearings showing where the so-called "Devonshire Treasure" was buried. Graham had given it to her, she said, just before he was captured, thinking—rightly as it turned out—that it would be safer on her person than on his. Welch's story was believed, as much for her intimate knowledge of the island as for the chart, and an expedition was mounted to hunt for the treasure. Welch went along, of course, and as quite an old woman set foot once again on Cocos. In the decades since she'd been there, however, the lay of the land had changed so much at the hands of visiting sailors that many of her identifying marks, including a huge cedar tree near which she had once camped for six months, had disappeared, and the expedition recovered nothing. Continue: Benito "Bloody Sword" Bonito's treasure. Cocos Island | Sharkmasters | World of Sharks | Dispatches E-mail | Resources | Site Map | Sharks Home Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule | About NOVA Watch NOVAs online | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Search | To Print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated June 2002 |

Cocos Island

Cocos Island

Spanish map of the world from 1622, with Cocos

indicated.

Spanish map of the world from 1622, with Cocos

indicated.

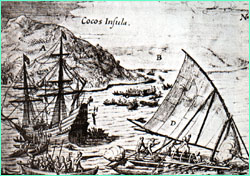

A drawing of Cocos Island in

its heyday.

A drawing of Cocos Island in

its heyday.