|

To speak the name of the dead is to make them live again.

—ancient Egyptian inscription

What's in a name? Well, in the case of Rameses I, no less than

immortality—and this for a man of humble roots. For "Rameses,"

which he began calling himself after becoming pharaoh in 1307 B.C.*,

has come down to us today as one of the most recognizable names from

ancient Egypt. For many it conjures up vast empires along the Nile,

colossal monuments in stone, pharaohs somehow loftier than kings

ruling over a civilization that rivals in singular magnificence any

the world has produced.

And Rameses I gave us more than just a name. He gave us a Dynasty,

the 19th, one of the most illustrious ancient Egypt ever knew. And

he gave us living legends: his son Seti I ushered in a period of art

and culture unrivaled in later Egyptian civilization, and his

grandson Rameses II earned the suffix "the Great" by building more

temples and erecting more obelisks and statues (and siring more

children) than any other pharaoh. No fewer than 10 subsequent

pharaohs proudly adopted the name Rameses, Rameses XI passing

on—and ending the so-called Ramesside period—237 years

after his namesake took the throne.

Yet Rameses I was not of royal blood. He became pharaoh when he was

already old by ancient standards (probably in his 50s). And he

reigned for less than two years. All of which makes his immortality

all the more remarkable.

Growing up in strange times

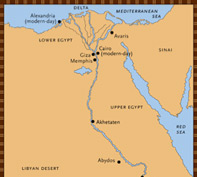

Rameses I was born in the mid-14th century B.C. His home lay near

Avaris, a town in northern Egypt situated on the far side of the

great fan-like Nile Delta from where Alexandria sits today (see

map). He came from a long line of soldiers; his father Seti, after

whom the future Rameses I would name his son, was a troop commander

and judge. The name that judge Seti and his wife gave the future

pharaoh was Paramessu.

Paramessu grew up in one of the most unusual periods in Egyptian

history. The pharaoh Amenhotep IV, better known as Akhenaten, who

assumed the throne about the time that Paramessu was born, shook the

foundation of Egyptian society. With the revolutionary zeal of a

Lenin or Mao, Akhenaten swept away the old religion, replacing it

with a monotheistic cult worship of the sun-disc Aten. He built a

new capital city, Akhetaten ("the Horizon of the Aten"), and moved

the seat of government there from Thebes, which had been the

pharaohs' capital for most of the 18th Dynasty. And he ushered in an

entirely new style of art, with figures—including his own

famously misshapen form—drawn with more realism than was

common in the erstwhile, more formal style.

Rameses I left a significant mark on Egyptian civilization—not

least his evocative name.

When Akhenaten died in 1333 B.C., his son Tutankhaten took his place

on the throne, even though he was only about nine years old at the

time. In the second year of his reign—no doubt at the

instigation of the two highest-ranking officials from his father's

court, Ay and Horemheb, who effectively ran the boy's

court—Tutankhaten dropped the "-aten" suffix from his name in

favor of "-amun." This signaled the start of the dismantling of

everything Akhenaten had done and the reinstitution of the old ways,

including belief in Amun, the King of Gods. When

Tutankhamun—aka King Tut—died heirless when he was about

17 years old, Ay and later Horemheb continued the restoration as the

last two pharaohs of the 18th Dynasty.

An abbreviated reign

Through all this, the soon-to-be Rameses I was rising rapidly in the

ranks of the military. He surpassed his father's position as troop

commander and eventually gained the favor of Horemheb, who himself

had been head of the army under Akhenaten. Indeed, during Horemheb's

reign (1319-1307 B.C.), Paramessu went on to become

vizier—roughly equivalent to today's prime minister—and

held a string of important titles: Master of Horse, Commander of the

Fortress, Controller of the Nile Mouth, Charioteer of His Majesty,

King's Envoy to Every Foreign Land, Royal Scribe, Colonel, and

General of the Lord of the Two Lands. Not bad for a soldier's son

without a drop of royal blood in his veins.

Paramessu's rise did not stop there, of course. Having become

Horemheb's friend and confidant, he ultimately became both coregent

with the pharaoh and, since Horemheb apparently had no heirs, his

hand-picked successor. Upon Horemheb's death in 1307, Paramessu

assumed the throne as Rameses ("Ra [the sun god] Has Fashioned

Him"). Pharaohs of the day took five different names, and one of

Rameses's others, his so-called Golden Horus name, was "He Who

Confirms Ma'at Throughout the Two Lands." Ma'at was a daughter of

the sun god Ra, and the name as a whole signified Rameses' desire to

continue the work of his predecessors to undo the heretical

handiwork of Akhenaten.

Like most pharaohs, Rameses I immediately set about doing things for

which he would be remembered. These pursuits took him to the far

ends of his kingdom, and even beyond. At Buhen in southern Egypt, he

made additions to the Nubian garrison. At Karnak Temple in

Thebes—where his son and grandson would later erect the Great

Hypostyle Hall, one of the greatest monuments of the ancient

world—Rameses I had reliefs carved on the massive gateway

known as the Second Pylon. Farther north at Abydos, the burial place

of the first kings of a unified Egypt, he began construction of a

chapel and temple (Seti I would complete it). Still farther north,

Rameses I reopened Egyptian turquoise mines in the Sinai, and he led

at least one military expedition into western Asia.

A name for the ages

Despite the promising start, Rameses I's reign ended so quickly that

his tomb was only partially complete when he died. In contrast to

the cavernous crypts of his successors, Seti I and Rameses II, his

is but antechamber in size. As in life, in death Rameses I did not

leave much behind, at least after ancient robbers had finished with

his tomb. When the Italian explorer Giovanni Belzoni discovered the

sepulcher in 1817, all that remained in the way of grave goods was

Rameses' damaged granite sarcophagus, a pair of six-foot wooden

guardian statues once covered in gold foil, and some statuettes of

underworld deities. His mummy was missing, too. The most important

surviving artifacts were well-executed paintings from the

Book of Gates, one of the Egyptian treatises on the

underworld, lining the walls of his burial chamber.

Yet for so brief a reign, and for having had just one child with his

wife Sitra, Rameses I left a significant mark on Egyptian

civilization—not least his evocative name.

*Note: Scholars still debate exact dates of ancient Egyptian reigns

and dynasties. The dates in this article come from the chronology

developed by John Baines and Jaromir Málek and used in their

book Atlas of Ancient Egypt.

|

|

Few today know the name Paramessu, but the name this

ancient Egyptian soldier took upon becoming pharaoh

resounds through the ages: Rameses. Here, a stone head

of Paramessu now in Boston's Museum of Fine Arts.

|

|

|

Egypt in Rameses I's day

|

|

|

In this painting from his tomb in the Valley of the

Kings, Rameses I is depicted between the falcon-headed

"soul of Pe" and the dog-headed "soul of Nekhen,"

spiritual beings that represented the traditional

regions of Lower and Upper Egypt.

|

|

|

Many experts see a physical resemblance between the

mummified head of what is now thought to be Rameses I

(top) and the heads of his son Seti I (middle) and

grandson Rameses II.

|

|

|