|

|

|

|

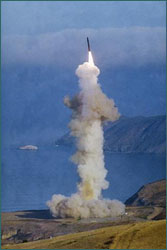

|  In the past quarter century, Russia and the United

States each have come close twice to launching nuclear missiles to counter a

perceived attack. Above, Russia's premier ICBM, the TOPOL M, in a test

firing.

In the past quarter century, Russia and the United

States each have come close twice to launching nuclear missiles to counter a

perceived attack. Above, Russia's premier ICBM, the TOPOL M, in a test

firing.

|

False Alarms on the Nuclear Front

by Geoffrey Forden

The Cuban missile crisis is the best-known example of narrowly avoiding nuclear

war. However, there are at least four other less well-known incidents in which

the superpowers geared up for nuclear annihilation. Those incidents differed

from the Cuban missile crisis in a significant way: They occurred when either

the U.S. or Soviet or Russian leaders had to respond to false alarms from

nuclear warning systems that malfunctioned or misinterpreted benign events.

All four incidents were very brief, probably lasting less than 10 minutes each.

Professional military officers managed most of them. Those officers had to

decide whether or not to recommend launching a "retaliatory" strike before

possibly losing their own nuclear first strikes. In three of the four

incidents, the decision not to respond to the alarm was made when space-based

early-warning sensors failed to show signs of massive nuclear attacks. The

fourth incident was caused by an inadequate early-warning satellite system that

was fooled into thinking that reflected sunlight was the flames from a handful

of ICBMs.

As the following brief history of those four incidents makes clear, space-based

early-warning systems played a major role in avoiding nuclear war. During the

1980s, a few specialized articles in the media hinted at the presence of those

systems. However, it was only during the Gulf War that the American public

truly became aware of U.S. capability to detect missile launches using

space-based assets. During that crisis, U.S. Defense Support Program (DSP)

satellites, first orbited in 1970, detected the launch of every Iraqi Scud

missile. The satellites made the detections from their orbits by "seeing" the

infrared light that the missiles' motors gave off during powered flight. The

warning of launches was transmitted to Patriot air defense missile batteries in

Israel and Saudi Arabia to support attempts to shoot down the incoming

warheads.

The association with the fighting of conventional war has obscured

the more important strategic role those systems have played: reassuring leaders

of the United States and Russia that they were not under nuclear attack. A

review of the four nuclear crises will better highlight that role.

Early on the morning of November 9, 1979, control centers for

American Minuteman missiles, such as the one above, went on high alert for a

harrowing several minutes.

Early on the morning of November 9, 1979, control centers for

American Minuteman missiles, such as the one above, went on high alert for a

harrowing several minutes.

|

|

The training tape incident

Shortly before 9 a.m. on November 9, 1979, the computers at North American Aerospace

Defense Command's Cheyenne Mountain site, the Pentagon's National Military

Command Center, and the Alternate National Military Command Center in Fort

Ritchie, Maryland, all showed what the United States feared most—a massive

Soviet nuclear strike aimed at destroying the U.S. command system and nuclear

forces. A threat assessment conference, involving senior officers at all three

command posts, was convened immediately. Launch control centers for Minuteman

missiles, buried deep below the prairie grass in the American West, received

preliminary warning that the United States was under a massive nuclear attack.

The alert did not stop with the U.S. ICBM force. The entire continental air

defense interceptor force was put on alert, and at least 10 fighters took off.

Furthermore, the National Emergency Airborne Command Post, the president's

"doomsday plane," was also launched, but without the president on board. It was

later determined that a realistic training tape had been inadvertently inserted

into the computer running the nation's early-warning programs.

|

In the "training tape" incident, Defense Support Program early-warning

satellites saved the day. Above, a $256 million DSP satellite goes aloft in

August 2001.

In the "training tape" incident, Defense Support Program early-warning

satellites saved the day. Above, a $256 million DSP satellite goes aloft in

August 2001.

|

However, within minutes of the original alert, the officers had reviewed the

raw data from the DSP satellites and checked with the early-warning radars

ringing the country. The radars were capable of spotting missiles launched from

submarines close to the U.S. shores and ICBM warheads that had traveled far

enough along their trajectories to rise above the curvature of the Earth. The

DSP satellites were capable of detecting the launches of Soviet missiles almost

anywhere on the Earth's surface. Neither system showed any signs that the

country was under attack, so the alert was canceled.

The computer chip incident

On June 3, 1980, less than a year after the incident involving the training tape,

U.S. command posts received another warning that the Soviet Union had launched

a nuclear strike. As in the earlier episode, launch crews for Minuteman

missiles were given preliminary launch warnings, and bomber crews manned their

aircraft. This time, however, the displays did not present a recognizable or

even a consistent attack pattern as they had during the training tape episode.

Instead, the displays showed a seemingly random number of attacking missiles.

The displays would show that two missiles had been launched, then zero

missiles, and then 200 missiles. Furthermore, the numbers of attacking missiles

displayed in the different command posts did not always agree.

Although many officers did not take this event as seriously as the incident of

the previous November, the threat assessment conference still convened to

evaluate the possibility that the attack was real. Again the committee reviewed

the raw data from the early-warning systems and found that no missiles had been

launched. Later investigations showed that a single computer chip failure had

caused random numbers of attacking missiles to be displayed.

The autumn equinox incident

On September 26, 1983, the newly inaugurated Soviet early-warning satellite system

caused a nuclear false alarm. Like the United States, the Soviet Union realized

the importance of monitoring the actual launch of ICBMs. However, the Soviets

chose a different method of spotting missile launches. Instead of looking down

on the entire Earth's surface the way U.S. DSP satellites do, Soviet satellites

looked at the edge of the Earth—thus reducing the chance that naturally

occurring phenomena would look like missile launches. Missiles, when they had

risen five or ten miles, would appear silhouetted against the black background

of space. Furthermore, when the edge of the Earth is viewed, light reflected

from clouds or snow banks has to pass through a considerable amount of the

atmosphere. That view reduces the chances that clouds and snow may cause false

alarms.

A Russian Oko early-warning satellite's hypothesized view of

U.S. missile fields at the time of the so-called "autumn equinox" incident.

A Russian Oko early-warning satellite's hypothesized view of

U.S. missile fields at the time of the so-called "autumn equinox" incident.

|

|

A satellite has to be in a unique position to view a recently launched missile

silhouetted against the black of space. To get that view, the Soviet Union

picked a special type of orbit that it had used for its communications

satellites. Those orbits, known as Molnyia orbits, come very close to the Earth

in the Southern Hemisphere but extend nearly a tenth of the distance to the

moon as the satellite passes over the Northern Hemisphere. From that position

high above northern Europe, the Soviet Union's Oko ("Eye") early-warning

satellites spend a large fraction of their time viewing the continental U.S.

missile fields at just the right glancing angle. However, shortly after

midnight Moscow time on September 26, 1983, the sun, the satellite, and U.S.

missile fields all lined up in such a way as to maximize the sunlight reflected

from high-altitude clouds.

Whether that effect was a totally unexpected phenomenon is hard to know. That

may have been the first time this rare alignment had occurred since the system

became operational the previous year. Press interviews with Lt. Col. Stanislav

Petrov, the officer in charge of Serpukhov-15, the secret bunker from which the

Soviet Union monitored its early-warning satellites, indicated that the new

system reported the launch of several missiles from the U.S. continental

missile fields. Petrov had been told repeatedly that the United States would

launch a massive nuclear strike designed to overwhelm Soviet forces in a single

strike.

Why did that false alarm fail to trigger a nuclear war? Perhaps the Russian

command did not want to start a war on the basis of data from a new and unique

system. On the other hand, if the sun glint had caused the system to report

hundreds of missile launches, then the Soviet Union might have mistakenly

launched its missiles. Petrov said that he refused to pass the alert to his

superiors because "when people start a war, they don't start it with only five

missiles. You can do little damage with just five missiles."

The Norwegian rocket incident

Early on the morning of January 25, 1995, Norwegian scientists and their American

colleagues launched the largest sounding rocket ever from Andoya Island off the

coast of Norway. [Sounding rockets collect data on atmospheric conditions from

various altitudes.] Designed to study the northern lights, the rocket followed

a trajectory to nearly 930 miles altitude but away from the Russian Federation.

To Russian radar technicians, the flight appeared similar to one that a U.S.

Trident missile would take to blind Russian radars by detonating a nuclear

warhead high in the atmosphere.

|  The trajectory of the Black Brant XII sounding rocket, which

triggered the "Norwegian rocket" incident.

The trajectory of the Black Brant XII sounding rocket, which

triggered the "Norwegian rocket" incident.

|

That scientific rocket caused a dangerous moment in the nuclear age. Russia was

poised, for a few moments at least, to launch a full-scale nuclear attack on

the United States. In fact, President Boris Yeltsin stated the next day that he

had activated his "nuclear football"—a device that allows the Russian

president to communicate with his top military advisers and review the

situation online—for the first time.

However, we can be fairly confident that Yeltsin's football showed that Russia

was not under attack and that the Russian early-warning system was functioning

perfectly. In addition to the string of radars surrounding the border of the

former Soviet Union, Russia had inherited a complete fleet of early-warning

satellites that, even by 1995, still maintained continuous 24-hour coverage of

the U.S. continental missile fields. In the early 1990s Russia had still

managed to launch replacement satellites for its early-warning system as the

previous ones died out—thereby retaining continuous coverage. Because of

those satellites, Yeltsin's display must have shown that no massive attack was

lurking just below the horizon.

Towards reliable early warning

The danger posed by those incidents was not the unauthorized or accidental

launch of a handful of nuclear-tipped missiles but the possibility that either

country might misinterpret a benign event—a computer training tape

mistakenly inserted into an operational computer or sunlight glinting off

clouds during a rare lineup of the sun, Earth, and satellite—and decide to

launch a full-scale nuclear attack.

Each incident caused officials to take steps to solve a specific problem. After

the training tape incident, the U.S. Department of Defense constructed a

separate facility to train operators so that a training tape could not again be

inserted into the computer running the nation's early-warning system.

Apparently, the Soviet Union launched a new fleet of early-warning satellites

into geostationary orbit simply to provide a second angle from which to view U.S.

missile fields. That expensive and redundant system ensured that at least one

satellite could search for missile launches free from sun glint.

After three of the four incidents, the U.S. government maintained that steps

were taken that would prevent any future false alarms. However, it had to wait

only seven months after the first incident (the computer tape incident) to see

that complex organizations, relying on even more complex machinery, can find

new and unexpected ways to fail. In fact, a comprehensive study of nuclear

accidents has shown convincing historical evidence that, despite measures taken

to prevent them, such accidents are inevitable.

|  Despite

careful measures to insure nuclear accidents never happen, history reveals that

such mishaps are inevitable. Are we prepared for the next one?

Despite

careful measures to insure nuclear accidents never happen, history reveals that

such mishaps are inevitable. Are we prepared for the next one?

|

The most recent example of solving the "last problem" was the Clinton

administration's initiative to share early-warning data with Russia. The

jointly manned center has been presented by the American side as a solution to

the decline of Russia's early-warning facilities. Russians familiar with the

negotiations, however, maintain that the center has no military significance.

That view is underscored by the choice of the site for the center: an old

schoolhouse nearly an hour away from downtown Moscow. In fact, U.S. Department

of Defense officials familiar with the Joint Data Exchange Center (JDEC) admit

that, even if the center had been active during the Norwegian rocket incident,

its only effect would have been to facilitate the launch notification issued

before the NASA launch.

Any assistance the United States provides must increase Russia's confidence in

the validity of its own early-warning systems. The JDEC fails that test. Russia

would never believe that the United States would pass along launch indications

if a U.S. nuclear attack had been launched.

|

|

Dr. Geoffrey Forden is a senior research fellow with the Security Studies

Program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. This article was adapted

with permission from a longer article Forden wrote entitled "Reducing a Common

Danger: Improving Russia's Early-Warning System." Published by the Cato

Institute, a Washington D.C.-based public policy research foundation, the

article originally appeared on May 3, 2001 as Cato Policy Analysis No. 399. To

see the full piece, go to www.cato.org/pubs/pas/pa399.pdf. |

Photos: (1) WGBH/NOVA; (2-3) Corbis Images; Illustrations and QuickTime animation: Geoffrey Forden, MIT.

The Director's Story |

False Alarms on the Nuclear Front

Global Guide to Nuclear Missiles |

From First Alert to Missile Launch

Resources |

Transcript |

Site Map |

Russia's Nuclear Warriors Home

Search |

Site Map |

Previously Featured |

Schedule |

Feedback |

Teachers |

Shop

Join Us/E-Mail |

About NOVA |

Editor's Picks |

Watch NOVAs online |

To print

PBS Online |

NOVA Online |

WGBH

© | Updated October 2001

|

|

|

|