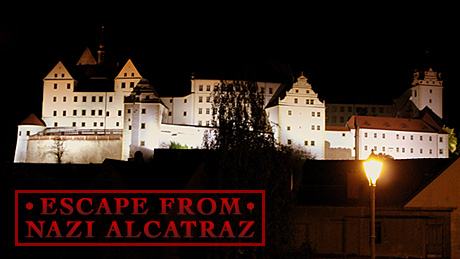

Escape from Nazi Alcatraz

A crack team rebuilds a glider that POWs hoped to catapult off the top of Colditz Castle. Airing June 17, 2015 at 9 pm on PBS Aired June 17, 2015 on PBS

- Originally aired 05.14.14

Program Description

Transcript

Escape From Nazi Alcatraz

PBS Airdate: May 14, 2014

NARRATOR: In the heart of Nazi Germany: an ancient castle, turned into a prison fortress, surrounded by barbed wire and searchlights, with walls six feet thick and one guard for every prisoner. It would be escape—proof.

But a group of British officers hadn't read the script. These prisoners conjured up one of the most audacious escape plans in history. Under the noses of their Nazi guards, they would secretly build a two—man glider, using floorboards and bed sheets, and hoped to launch it from the roof of the castle.

But the war ended before they could carry out their plan. The prisoners were released, and the plane lost forever.

HUGH HUNT (Cambridge University Engineer): Jess. Hi, Jess, I'm Hugh.

NARRATOR: Now, NOVA is back behind the walls of the fortress, to find out, could this crazy scheme have actually worked?

Led by Cambridge engineer Hugh Hunt, a crack team will reconstruct the glider in the same secret attic.

HUGH HUNT: It's huge.

NARRATOR: And they'll retrace some of the castle's other escape routes, to discover what extraordinary efforts these men made to try to get out.

For Hugh, it's personal. One of the men imprisoned here was his uncle.

HUGH HUNT: He was away from his family for four or five years; really tough.

NARRATOR: Finally, following the prisoners' plans, they'll try to catapult the glider from the castle roof, using a bathtub full of concrete.

HUGH HUNT: The chain hoist is stuck.

Oh, it's moving again.

NARRATOR: After a 70—year wait, at last, we'll find out. Were the prisoners about to fly to freedom or plunge to certain death? Escape from Nazi Alcatraz, right now, on NOVA.

MIKE: Now!

NARRATOR: High above the scenic town of Colditz, Germany, there looms an imposing fortress, once a medieval castle. Seventy years ago it was transformed into a notorious Nazi prisoner—of—war camp. Today, it's mostly rundown and empty, but during World War II, these rooms were filled with Allied officers who were caught trying to escape from other camps. The ghosts of these men still haunt the place.

GEORGE DREW (Former Colditz Prisoner): We were marched up to the camp between lines of horrible sentries. Someone yelled out, "Welcome to Colditz." And we weren't very happy, because we didn't want to be there.

NARRATOR: As officers, it was their duty to escape. This man is here to investigate how: Hugh Hunt, engineer.

HUGH HUNT: It's a small space, and it must have been very cold and shaded in the winter. And this was their exercise yard, with maybe 500 prisoners out here, 500!

NARRATOR: This home movie, shot by a German guard, was discovered while making this film. It's the only known footage of prisoners in Colditz.

There were over 170 escape attempts made, but one scheme must rank as the most audacious. In the final months of the war, a group of British prisoners plotted to fly their way out of the fortress. Their ticket to freedom was to be a homemade glider, built from scraps stolen from the Nazis and launched off the roof.

The prisoners planned to build their runway on the ridge of this roof, 34 meters above the ground. Hugh is in charge of finding out if this mission impossible would have stood any chance of working.

HUGH HUNT: Brave guys, I have to say. We'll do the best we can, and we'll find it tough, but nothing like as tough as they would have found it.

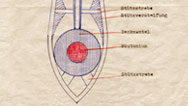

NARRATOR: The prisoner's plan was outrageously risky. Their glider would carry two men, sitting back to back. To launch it off the roof, they would fasten a rope to the nose of the glider, run it over a pulley and tie it to a bathtub full of concrete.

Dropping the ton weight would catapult the glider off the roof. Then, they'd have to set the plane down safely in a field and continue their escape on foot—a piece of cake.

The brains behind this extraordinary idea was 27—year—old Bill Goldfinch, an R.A.F. pilot who'd already toyed with the idea of flying to freedom, from his previous camp, by dangling from a kite. His inspiration for the glider came from a surprising source: the view from a window on a winter's day.

L.J.E. "BILL" GOLDFINCH (Former Colditz Prisoner): This window faced Colditz town, looked out over Colditz town, to the west, I suppose, more or less. And the wind was blowing on the face of this window, and it was snowing. But what appealed to me was that the snowflakes weren't coming down, they were actually just drifting up and over the top. We could watch the force of the wind at work on them. And what a smooth flow it was of air, coming along, rising up, and that said, "This is a good place to launch a glider." That was the thought. That was, "Eureka!"

NARRATOR: Goldfinch built his glider, and his original detailed plans still exist, but there's only a crude sketch to show how he was going to launch it off the roof.

Turning Bill's scribble into a fully functional glider launcher is some challenge. That's where Hugh Hunt comes in.HUGH HUNT: Right, let's see if I can… It is possible to just get it to be stationary.

NARRATOR: Hugh lectures on mechanical engineering at Trinity College, Cambridge, and he knows all about the science of falling objects.

HUGH HUNT: One of the things I do here in Trinity is I look after the college clock. And the college clock has got weights, which fall, and there's pulleys. So one of the things I'm quite good at is thinking about how weights and pulleys work. So the question then is, if I wanted to launch the glider, could I launch it by having weights and pulleys?

NARRATOR: The prisoners spent 10 months building their glider. With the help of some special recruits, Hugh hopes to do it in two weeks.

HUGH HUNT: Tony, welcome.

NARRATOR: Tony Hoskins is an ex—Virgin—airlines engineer who now builds and repairs gliders professionally.

HUGH HUNT: Did you enjoy the drive?

OTHERS: Er, no.

NARRATOR: Hugh has asked Tony and his team to build an exact replica of Goldfinch's glider.

HUGH HUNT: That little bit of roof, up there, is where we're going off.

NARRATOR: Their workshop will be the same attic the P.O.W.s used nearly 70 years earlier.

TONY HOSKINS (Glider Builder): It's bigger than I imagined.

NARRATOR: There is only one known photograph of the glider. It was taken in this very room, after the castle was liberated, in April, 1945.

Tony's brought all the raw material he needs to build the glider with him from the U.K., but Bill Goldfinch's men didn't have that luxury. They made their glider out of whatever they could steal.

BILL GOLDFINCH: We were in a great big castle, lots of wood, lots of stone, lots of metal about. And it lay all around you for the taking. And you could help yourself to what you wanted, which is exactly what they did. We said, "We want that bit of wood," so we'll take it then.

HUGH HUNT: Now we're going to get to a tricky bit here. I think what…

NARRATOR: Tony will be following Bill Goldfinch's plans to the letter, but there's one key difference.

TONY HOSKINS: Ah, this is our intrepid hero. He's taken a bit of a knock on the way up the stairs.

NARRATOR: Tony's not prepared to risk the life of a real pilot, so the glider will be flown remotely, via a radio link from the field below.

HUGH HUNT: It looks very good.

NARRATOR: Hugh's joined by military historian Sebastian Roberts. As an ex—Major General in the Irish Guards, he understands the mindset of the young officers imprisoned here.

SIR SEBASTIAN ROBERTS (Military Historian): An English public school education is a good preparation for prison, and the large majority of those who were sent to Colditz had been through the English boarding school experience, and that certainly prepared them in several ways, psychologically.

Most of the British were in dormitories on this side here.

NARRATOR: One of the British prisoners was William Faithful Anderson, Hugh's uncle.

ANTONY: Hugh! Nice to see you. How are you? Long time no see.

NARRATOR: Will Anderson died several years ago. His son Antony looks after his father's archive.

HUGH HUNT: I can't remember if I've ever been up here.

NARRATOR: Hugh went to see his cousin before coming to Colditz.

ANTONY: There's aged nine months. And, look, a week before Daddy went to France, May, 1940. And a week later he was gone.

NARRATOR: Like Hugh, Will Anderson studied engineering at Cambridge. But he joined the army, and by the beginning of the war he'd risen to the rank of Major in the Royal Engineers. His wife Kathleen was pregnant with their second child, and Antony was just a few months old.

ANTONY ANDERSON: This is Mum's diary. (Reading) "May 1st, 1940, awful day has come. At 8 a.m., after breakfast together, Antony and I said goodbye to Will."

And that was all she saw of him for the next five, five and a bit more years.NARRATOR: Uncle Will's unit was sent to France to fight the Nazi troops sweeping across Europe. But like the rest of the allies, they were forced to retreat. At Dunkirk, the British carried out a desperate evacuation, but not everyone made it home.

Thirty—four—thousand British troops were captured, defending the beaches, and sent to prison camps across occupied Europe. Hugh's uncle was among them.

A year later, he was caught trying to tunnel out of his camp and sent to join the hardened escapers in Colditz.

HUGH HUNT: (Reading) "My own Darling Kathleen, I got here on Thursday after an interesting journey of more than a day. This is rather a very special sort of camp," [exclamation mark]. "We have 200 French and Belgians, 80 Poles and 37 British officers. All a most excellent and enterprising lot."

NARRATOR: Will was a keen amateur painter and began to chronicle life in the castle, but he soon found another outlet for his artistic talents. He became one of the camp's best forgers, drawing, by hand, perfect copies of printed German travel documents. This was essential kit for prisoners trying to break out. And it was in hot demand: Allied officers made over 170 escape attempts from Colditz, during the war.

SEBASTIAN ROBERTS: They knew that it was their duty to escape. And indeed the Germans understood this as well; it was the duty of German officers to escape, if they were captured.

The Germans had this maddening phrase they spouted at you when you were first captured. They thought they we being kind I think. "Fir Sie der kieg ist verbei," "For you, the war is over." But it jolly well wasn't going to be over. And this was the one thing we could do, and should do, would be to escape.

NARRATOR: But breaking out of the most secure prison camp in Germany wouldn't be easy. The central courtyard was a prison within a prison, enclosed on all sides by the rooms where the prisoners ate and slept. The only exit was blocked by three sets of heavily guarded gates. There was one guard for every prisoner. The castle's walls were six feet thick. Beyond them lay a series of eight—foot—high barbed wire fences, patrolled by sentries 24 hours a day. Floodlights lit the castle at night, and raised machine gun positions covered every possible exit.

Tunneling out seemed impossible, too. The castle sat on an outcrop of solid rock.

And even if prisoners were to get out of the castle, they were still nearly 400 miles from the nearest neutral country, Switzerland.

But in 1941, this didn't deter a group of recently arrived Dutch prisoners, who thought they'd spotted a weak link in the German ring of steel. Several times a week, prisoners were escorted down to a small park next to the castle for exercise. Although the park was heavily guarded, the Dutch saw this as a chance to escape.

SEBASTIAN ROBERTS: They'd recced here and discovered that there was a manhole, heavily bolted down with steel bolts, and they became convinced that this offered an opportunity.

They played down there on the exercise area, a game like rugby. It was extremely violent, and it resulted in big seething masses of scrummaging Dutch officers, which was a perfect opportunity for two of their number to make their way into the manhole.

Two guys got in and one of them had the original bolt with him. A third man, part of the scrum, quickly put in place a fake bolt which was actually made of glass.

When the scrum ended, there was no apparent change to the manhole. The German guards noticed nothing, exercise time ended, and the Dutch marched back up to the castle, leaving two men under an apparently completely locked manhole.

NARRATOR: The men, naval officers Hans Larive and Francis Steinmetz waited until darkness fell, and the nearest sentries were over a hundred meters away. That's when the glass bolt came in.

SEBASTIAN ROBERTS: They bothered to put the real bolt back, because they thought they might be able to use this particular place again, and they did, twice, successfully.

NARRATOR: Altogether, six Dutchmen took the manhole route to freedom, and four made it all the way to neutral Switzerland. Each time, the Germans hadn't even realized they were missing.

SEBASTIAN ROBERTS: The Dutch were masters of ingenuity to cover their escapes. They used dummies to answer the names of the escaped at the frequent role calls, and when the Germans did a head count, all the heads were there.

The dummies were extraordinarily lifelike. This photograph was taken after a dummy had been discovered. The Dutchman holding him is justifiably very proud of what he's got there, because this worked on several occasions.

NARRATOR: When he discovered the ruse, the camp's head of security, Captain Reinhold Eggers, was so impressed that he had Dutch officers pose with their dummies for the camera.

He displayed these images in a museum dedicated to the art of the escaper. It included homemade civilian clothes and fake German uniforms, knocked up on a hand—built sewing machine; German army insignia cut from linoleum; and dummy rifles made from paper and wood.

But Eggers didn't assemble the collection for his own amusement. He invited guards from other camps to come along and learn about the resourcefulness of the enemy.

KEITH LOCKWOOD (Former Colditz Prisoner): He was a very good security officer; there's no question of that. He was a thorn in our side. He had a job to do to keep us in, and our job was to get out. And he was good.

JESS: Timber!

NARRATOR: Today, the would—be escapers don't have to worry about prying Nazi guards. And they are experienced glider builders, unlike the men who designed the original aircraft.

BILL GOLDFINCH: It was a matter of applying what knowledge one had to say, "Well, how big should the wing be? How much has it got to weigh? How strong was it going to be?" We had to work all this out on a bit of paper.

NARRATOR: R.A.F. pilot Bill Goldfinch knew how to handle an aircraft, but had no idea how to build one. Luckily, Colditz had a surprisingly well—stocked prison library.

HUGH HUNT: In Colditz, he found, in the prisoners' library, these two volumes. And the name of the book? Aircraft Design. Now, what better book? You may as well have had Tunneling for Dummies and Forgery Made Easy.

I look inside these volumes…you see the most incredibly detailed pictures. This is the section of a wing. This is all the basics of what you need to fly a plane with a couple of people in it. And that's what he wanted: simple, to the point; beautiful books.

NARRATOR: To turn his ambitious design into reality, Goldfinch teamed up with one of the best craftsmen in the camp, fellow R.A.F. pilot Jack Best.

JACK BEST: We had been mates ever since we'd been prisoners, I think, really, so we more or less talked with one voice. We were called the "two old crows" or the "wicked uncles."

BILL GOLDFINCH: Or the wicked uncles.

NARRATOR: Altogether, 16 British prisoners built the glider.

HUGH HUNT: So, Tony, I want to show you something down here.

NARRATOR: They concealed themselves behind a false wall at one end of the attic, above where Tony's working.

HUGH HUNT: You guys have got that huge space down the bottom; this is all they had. They reckon it's seven feet according to the various records. They built a wall here. My Uncle Will was responsible for designing the wall.

TONY HOSKINS: Fantastic.

SEBASTIAN ROBERTS: They shortened an attic with a fake wall, which was never discovered, behind which a whole glider was constructed, a glider large enough to take two people, a glider engineered with supreme skill.

TONY HOSKINS: That's it. That's the workshop.

NARRATOR: In the derelict former prisoner's quarters, Hugh's on the hunt for the most important part of the mechanism that will catapult the glider off the roof.

HUGH HUNT: We're looking for bathtubs, bathtubs!

This used to be a mental hospital and asylum.WALDO: What? After the war? Creepy place, isn't it?

HUGH HUNT: Aha!

WALDO: Wow, look at that.

NARRATOR: A bathtub, liberated by the prisoners from their own washrooms, would have made a perfect counterweight for the glider. When empty it would be light enough to move around. Once in position it could be filled with concrete to the desired weight.

HUGH HUNT: It's a shame there's no hot and cold running water.

WALDO: It's all right, we've got plenty of dust.

NARRATOR: Up on the roof of the castle, carpenters have been building the wooden platform that will form the glider's 40—foot—long runway.

Hugh has to sign off on the work, but he hasn't got a head for heights.

HUGH HUNT: I've been psyching myself up for this for a few days. I'm all right. I'm okay. I'm okay.

There we go.

NARRATOR: What the runway lacks in length, it makes up for in altitude.

HUGH HUNT: Nice view!

NARRATOR: The runway is higher than a 10—story building. Hugh's got it easy; the original glider men wouldn't have been secured to the roof by ropes.

WALDO: Perfect height for a little trip hazard.

HUGH HUNT: Just don't get too far away from me, Waldo.

MIKE: If you want to go on your hands and knees and peek over the edge, that's fine.

NARRATOR: The courtyard is 160 feet below. This should give the bathtub the drop it needs to accelerate the plane up to takeoff speed.

HUGH HUNT: Woo hoo! Hi, bathtub.

NARRATOR: Hugh's men are clearly visible on the roof, so how were the prisoners going to work without being spotted by the guards below?

Their solution was typically bold: they would build their runway under cover of darkness, in a single night.

Although the castle was lit by floodlights, the apex of the roof was in shadow, allowing the men to work without being seen. The glider workshop was directly behind the runway roof.They planned to knock a hole in the wall and lay out a line of tables, taken from their rooms, along the ridge. This would be their runway. Then they'd assemble their glider, before hanging their bathtub in place. They'd be gone before the sun came up.

It's the end of week one. The glider's wooden framework is almost finished, so Hugh turns to the mechanism that will launch it off the roof. He starts with the idea sketched by Bill Goldfinch in 1944, and sets up a rig to do a scaled—down test. Standing in for the plane is a block of wood, wrapped in cloth. They'll try to launch it, using a bath full of water.

HUGH HUNT: We don't want anybody standing in the line of that direction. That's very important, so please stay back there.

The P.O.W.s of course didn't have the luxury of doing these kinds of tests. Well the P.O.W.s took big risks. They took risks with their lives, with other people's lives, that was the nature of war.

Okay. Three, two, one.

Hey, Tony, I think we need some wings.

NARRATOR: As Hugh is discovering, generating enough speed to get the glider airborne is going to be his biggest challenge. The plane needs to reach 40 miles per hour, but over such a short runway this will take the acceleration of a Formula 1 car. Is a falling bathtub really up to the task?

With a cable running over a single pulley, the glider moves at the same speed as the falling bathtub, but that's not fast enough to fly.

No matter how heavy the bathtub is, it can't accelerate faster than gravity, or 1G. And, at 1G, the glider won't have reached launch speed by the end of the runway.

Hugh's solution is to run the cable around a second pulley. The pair of pulleys acts like a pair of gears. Now for every meter the bathtub falls, the glider moves two meters forward. With the glider moving twice as fast as the falling bathtub, it should be able to reach launch speed by the end of the runway. At least, that's the theory, but will it work in practice?

HUGH HUNT: Okay, five, four, three, two, one.

There we go.

NARRATOR: The double pulley has sped up the block, but according to Hugh's calculations it's not enough.

HUGH HUNT: But look, I've been able to analyze the data. And what you do, you've got all these distances, and you've got the times by counting frames. And distance is a half A T squared, where A is acceleration. So, I've got distances, I've got time, so…bit of a parabola through it…I work out acceleration.

TONY HOSKINS: Right, and you wanted?

HUGH HUNT: 1.2 g.

TONY HOSKINS: And we absolutely must need 1.1?

HUGH HUNT: 1.1 g.

TONY HOSKINS: And you had?

HUGH HUNT: About 0.84. So our launch speed, I've worked out, would be about 29, 30, 31 miles an hour, if we have exactly this situation.

NARRATOR: The glider won't fly unless it reaches 40 miles an hour. The double pulley should have greatly increased the speed of the test launcher, but just like Bill Goldfinch's glider, the block has to slide on a wooden skid rather than wheels, and friction between the skid and the runway is slowing it down.

Perhaps Colditz' do—it—yourself can help.

HUGH HUNT: Ich.

Yah, Reibung.SHOP ASSISTANT: Reibung? Ah genau?

HUGH HUNT: Fur Das flug.

We want to have Reibung very small, so that…SHOP ASSISTANT: Aha! Yes, okay.

NARRATOR: The shop assistant offers Hugh some scrap metal sheets.

HUGH HUNT: This looks rather good.

SHOP ASSISTANT: It's a present!

NARRATOR: The smooth metal sheets should reduce the friction between the glider and the runway, but will that make it fast enough to carry it beyond the castle walls?

By the beginning of 1942, over 20 British prisoners had tried to escape from Colditz, but none had made it home. Many had failed for a very British reason: they couldn't speak the local language.

So, for the next attempt, scheduled to take place during a prison concert, Brit Airey Neave teamed up with Dutchman Tony Luteyn, who spoke fluent German.

To get away, they would drop through an opening made by the prisoners into a corridor beneath the stage.

TONY HOSKINS: There was a rope hanging, a rope made of sheets with some knots in it, so you could climb downstairs into the room underneath the stage.

NARRATOR: The corridor underneath the theatre led to the German guardhouse. Dressed in fake German uniforms, the two escapers marched straight through a room full of guards, towards the exit.

TONY HOSKINS: The sergeant of the guard opened the front door to let us out.

NARRATOR: Luteyn's fluent German ensured an easy passage through hostile country. After 48 hours they were in neutral Switzerland. The British, thanks to the Dutch, had made their first home run.

In two days' time, the glider team will make their own escape attempt. Tony's finished the aircraft's wooden frame, but he's got to cover it in fabric before it will fly. His choice of material would meet the approval of the original glider men.

CORRAN PURDON: The fuselage was covered with our bedsheets. We had sort of blue and white checked bedsheets, and I do remember helping putting these sheets on. And then I remember sitting with a sort of brush thing, dabbing what I was told was "dope" on it, as well.

NARRATOR: Dope is a type of varnish that's applied to the fabric on airframes to pull it taut and make it airtight. But the prisoners didn't have access to any, so they had to improvise, with porridge, made to the Colditz recipe that used millet instead of oats.

The starch in the porridge shrinks as it dries, tightening the fabric, at least that's the theory.

TONY HOSKINS: We've spent just over a week making a rather lovely Colditz glider, and you're asking us to paint porridge on it. I really don't want to paint that on my airplane.

NARRATOR: While Tony slaves over a hot stove, Hugh goes exploring. He wants to find his Uncle Will's old room, but there are hundreds to choose from.

HUGH HUNT: Oh, no, this is the wrong direction, completely.

NARRATOR: Will painted the same view from his window, through all the seasons for four years, so Hugh's using one of these pictures to help him find the room.

HUGH HUNT: That's the direction, but it's not a room. I doubt he'd be painting in a corridor.

Looking out this window, then, I can see the archway, clock tower the right level, can see the trees. No doubt at all, this is the right view.NARRATOR: One of the many letters he wrote from this room was to his four—year—old son, Antony.

HUGH HUNT: (Reading) "Many happy returns of your birthday. I wish I could be at home for it, but I really think I may be back for the next one. Anyway, I promise you and David," [that's his younger brother] "a special extra one, directly I come home. I hope you like school."

You know, it's funny, I'm away from my kids this week for just two weeks, and he was away from his family for four or five years; really tough.NARRATOR: Last night, the team rebuilding the Colditz glider covered its fabric surfaces with porridge made from millet seed. It was supposed to pull the cotton fabric taut, but they were skeptical that it would work.

BEN WATKINS (Glider Builder): It could be tighter. The other wing, funnily enough, came out better. Actually, we're really happy with it, turned out really well. And I'm really glad we used the millet. What can I say?

NARRATOR: Now the millet's done its job, the glider's ready to be taken out and assembled on the roof, where they're putting the finishing touches to the runway.

But there's one last job before everyone leaves for the night. During the war, the prisoners' plan was to knock a hole in the wall at the end of the attic and pass the glider straight out onto the runway.

The castle authorities have drawn a line at Hugh doing the same, but they have allowed him to open a hole in the roof instead. But it will make getting the glider onto the runway much more difficult.

HUGH HUNT: We're going to convene at 5 tomorrow morning, with a view to launching at around 10 tomorrow morning, perhaps 11, at the latest, because there's some bad weather coming in, and it's going to start getting blustery. One of the big concerns is that if the wind comes in from one side, it pushes up on one wing, and it's going to be very, very hard to assemble the glider, and even fly the glider, if the wind comes up from one side. So, we've got to be out there by 11, 12, at the very latest. So we've got work to do.

NARRATOR: D—day, June, 1944: over 150,000 Allied troops invaded northern France. The tide of the war was turning; the Allies were finally on top. But as the fighting got fiercer, conditions inside Germany deteriorated. Food became scarce. German society was falling apart.

Inside Colditz prison, rations were cut, and prisoners were beginning to starve.

VETERAN: If it's pure hunger, you really are thinking different things, and it does take over your complete thought. You have no other thought except food.

NARRATOR: It was particularly bad for any prisoner caught trying to break out. The Nazis had issued an order that guards were to shoot escapers on sight. As this German propaganda poster put it, escaping had ceased to be a sport.

By the final year of the war, security officer Eggers had blocked off all routes to freedom. The prisoners' last hope was their most desperate plan of all.

SEBASTIAN ROBERTS: They'd been forced by the success of the Germans, in foiling other attempts, to be ever more imaginative. The glider was an absolutely serious escape attempt. I'm absolutely certain that the two men who were going to be in the glider were, above all, aiming to escape.

NARRATOR: It's launch day. The weather's perfect for flying now, but after lunch the wind is due to pick up. Already, Ben's seeing trouble ahead.

BEN WATKINS: The wind is coming from this direction, and that's our takeoff direction, so, it means we have an element of tailwind and crosswind at the same time, which isn't so good.

NARRATOR: Their first job is to get the glider onto the roof, and that's not going to be easy.

JIM: See the wind picking up.

TONY HOSKINS: It is picking up.

NARRATOR: They're using a system of ropes to lift the pieces of glider around the clock tower and onto the roof. They've rigged a fabric sling to carry the wings, but they are light and very fragile.

JESS: It's slipping.

NARRATOR: The process is taking longer than they expected. Already, they're behind schedule.

TONY HOSKINS: It's getting really close.

JIM: Whoa, whoa, whoa, keep it away from the wall there, Waldo, if you can.

TONY HOSKINS: Phew…

NARRATOR: Now the components are on the roof, they have to put them together quickly while conditions are calm.

HUGH HUNT: Do you want this up?

TONY HOSKINS: Not yet, Hugh.

NARRATOR: With half the town closed off, the other half is crammed full of spectators.

At last, the glider's in one piece. Nothing like it's been seen in Colditz since the war.

CORRAN PURDON: I mean, there was no doubt about it. It was a super looking glider, when it was finished. And I saw it when it was finished.

NARRATOR: Although the original glider never made it out of the attic, that it was conjured out of thin air by starving prisoners speaks volumes about the Colditz spirit.

A successful launch today, after a 70—year wait, would close a chapter of history. No pressure then, Hugh.

HUGH HUNT: Tony, what do you reckon? Looks fantastic!

TONY HOSKINS: It does, but we need to get going as soon as we can. Yep, get them going.

HUGH HUNT: Well, can I radio up and get that bathtub going up.

NARRATOR: It's midday.

Hugh and Tony will oversee the launch from the landing field below the castle.

HUGH HUNT: We have sight of bathtub.

NARRATOR: They'd wanted to launch two hours ago, and there are signs that the wind is picking up.

PAT WILLIS: It does show, up the top there, that there's quite a crosswind. Whatever the wind is doing up there, I just hope it's not too breezy.

NARRATOR: Pat Willis has more reason than most to be worried. He's the man at the controls. He'll pilot the glider using a hand—held radio control unit. Tony will monitor a live video link from the cockpit and feed him information during the flight.

HUGH HUNT: We haven't taken the bathtub up to the full six meters before. And it's not moving anymore, and it seems as if the chain hoist is stuck.

MIKE: About a meter and a half to go.

HUGH HUNT: Oh, it's moving again, yeah, moving.

JACK BEST: I wanted to have the bath timed, so that when it went down with a bang and set the glider off, there was a German goon underneath patrolling, so we'd squash one of them on the way. But that was ruled out of order, it wasn't cricket.

MIKE: Dermot, you're there.

HUGH HUNT: Woo hoo, bathtub up. Are you getting as shaky as I am?

NARRATOR: They'll be ready to launch, once Pat has done his final checks.

PAT WILLIS: Right aileron, both sides…one up, one down.

BEN WATKINS: Right aileron is down, but the left's one's neutral.

HUGH HUNT: Say again?

MIKE: Right is down, left is apparently neutral.

PAT WILLIS: Is the left moving at all?

BEN WATKINS: No, the left one's not working.

MIKE: It's not working?

BEN WATKINS: Yeah, no, it's not working.

NARRATOR: The left aileron, the flap on the far wing, isn't moving. Without it, Pat can't control the glider. If they don't fix it, they can't fly.

Tony and Hugh have no idea what's gone wrong.

PAT WILLIS: Okay.

NARRATOR: With strong winds on the way, they must fix it soon, or the launch will be off.

BEN WATKINS: Oh, crap. It was working.

NARRATOR: There's only one man who knows how to fix it, and only one who can reach it: rope man, Waldo.

PAT WILLIS: Lower the panel down.

NARRATOR: So, Pat has to talk him through what do, from the roof below.

No one said escaping from Colditz was going to be easy.

PAT WILLIS: Unplug the plug from that, which goes on the receiver. Right next to it, you'll find a red one.

NARRATOR: They discover that the problem lies with one of the electric motors, called servos, that are supposed to move the aileron up and down.

PAT WILLIS: The only thing to do is disconnect the arm of other servo and screw the whole panel back in, as is, and run with one servo. It looks like a servo's gone down.

NARRATOR: Waldo's heroics seem to have done the trick; the aileron's working. But they're now four hours behind schedule.

PAT WILLIS: The weather report says the wind is going to pick up, so we need to go earlier rather than later.

NARRATOR: Bill Goldfinch and Jack Best never got this far with their glider, but they still had an answer to the question, "Would it have flown?"

JACK BEST: Oh, yes, don't you agree?

BILL GOLDFINCH: Well, I think it would have certainly descended to Earth.

PAT WILLIS: We're ready to go down here.

TONY HOSKINS: I've got video link.

PAT WILLIS: We've got video link.

NARRATOR: Hugh's glider had better do more than just descend to Earth, for the sake of Colditz town.

MIKE: We're all clear and ready to go.

HUGH HUNT: Everyone happy? Anyone objecting?

NARRATOR: Right on cue, the wind starts gusting.

HUGH HUNT: Thirty seconds.

NARRATOR: The crosswind is lifting the glider up on one side.

MIKE: Ready, Jim?

NARRATOR: Rope specialist Jim crouches under the wing, ready to pull it level by hand.

MIKE: Fifteen, ten, five, and we're for go.

JIM: No, it's not lined up, it's not lined up. It needs to tip back this way, the glider. It's leaned over loads.

MIKE: Just waiting for the wind to tip over the right direction, and we will go.

JIM: Don't pull the trigger quite yet, Mike.

MIKE: Ready?

JIM: Aaah, it keeps going back. Now!

JESS: Oh.

MIKE: It's flying! It's still flying.

HUGH HUNT: Way hey!

Alex, how's…Alex…Oh, no! Alex!

PAT WILLIS: I dumped her, because I didn't want it going through people's property. I was really worried about that. But she came off there. Reactions are very, very slow, but that was majestic.

NARRATOR: During the war, this empty field was much bigger, so the prisoners would have had room to land safely and make their getaway.

It's a different story today.

TONY HOSKINS: As you see, we're in a fairly tight environment, with the river, with people's gardens, property and everything else, so it's a small field to hit. And we hit it. If it wasn't for these fences here and the property here, if you'd been able to straighten up and just continue on down there, you could have continued on, probably, to a relatively safe arrival.

HUGH HUNT: Had this been a for—real launch, with a for—real escape, with real people wanting to get away, they'd have put themselves down safely, and they'd have got away.

NARRATOR: And with a bit of luck, Bill Goldfinch would have fared better than Alex the polystyrene pilot.

JESS: Look, look, look. Watch this. He can talk now!

NARRATOR: The glider had speed to spare coming off the runway, but she was difficult to fly. Even so, Pat managed to steer clear of the town and put her down in the field.

HUGH HUNT: Here, standing in the field, we had just no idea whether this was going to work. And even as the glider came off the end, and it went down like this, and you know, "It's not going to work. It's going to end up in the village!" But up it came. And, oh, that was just an unbelievable moment. You just couldn't beat it. We had no idea. And there it is.

TONY HOSKINS: We have shown that launching a glider from the roof of Colditz by bathtub method is possible. It is definitely possible. It's tricky, and it's quite stressful at times, but it is possible.

HUGH HUNT: Well, I really do appreciate what they had to do. It would have been a very risky endeavor. What an ask! But yeah, they'd have done it. I'm sure they'd have done it.

NARRATOR: Troops from the United States First Army liberated Colditz castle on the 16th of April, 1945. A journalist attached to the unit took the only known photograph of the glider.

What happened to the aircraft afterwards is still a mystery. Bill Goldfinch and Jack Best had to leave it in Colditz, because, finally, they were going home.

Will Anderson had been away for over five years. The Britain he knew had disappeared, and loved ones had changed beyond recognition. Like millions of others, he, too, bore the scars of war and long imprisonment.

Will's son Antony was five years old when his father returned.

ANTONY: I don't think it was easy for my mother or my father. I think they both would have admitted it was jolly difficult adjusting. And we were attached to my mother, and so on, you know? And it took him a while to understand that, that these years had gone by.

NARRATOR: As good as his word, Will Anderson treated his children to the special "extra" birthday he'd promised in his letters.

ANTONY: Three ducks. That's the mummy duck.

NARRATOR: Putting some of the skills he'd learned in Colditz to good use, he made these waddling ducks out of a packing case and gave them to his young sons as presents.

Antony has kept them all these years.

Broadcast Credits

Mike Coles

Footage Farm

Imperial War Museum

Schlí¶sserland Sachsen

Colditz Museum

The City and People of Colditz

Orchestra of the Technical University of Dresden

Modelflugsportverband Deutschland e.V

Deutscher Aero Club e.V

The Durand Group

Fiddlers Green Paper Models

Matthias Hergt

Astrid Schnotalle

Cambridge University Library

Cambridge Gliding Centre

John Luker

Musikvergnuegen, Inc.

Rob Morsberger

Eddie Ward

Produced by Windfall Films Ltd. for NOVA/WGBH Boston in association with Channel 4.

© 2011 Windfall Films Ltd.

Additional Material © 2014 WGBH Educational Foundation

All rights reserved

This program was produced by WGBH, which is solely responsible for its content.

IMAGE:

- Image credit: (Colditz Castle)

- calflier001/Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Participants

- J.W. "Jack" Best

- Grismond Davies-Scourfield

- Former Colditz Prisoner

- George Drew

- Former Colditz Prisoner

- L.J.E. "Bill" Goldfinch

- Former Colditz Prisoner

- Tony Hoskins

- Glider Builder

- Hugh Hunt

- Engineer

- Keith Lockwood

- Former Colditz Prisoner

- Tony Luteyn

- Former Colditz Prisoner

- Corran Purdon

- Former Colditz Prisoner

- Sir Sebastian Roberts

- Military Historian

- Ben Watkins

- Glider Builder

Preview | 00:30

Full Program | 53:07

Full program available for streaming through

Watch Online

Full program available

Soon