D-Day's Sunken Secrets

Dive teams, submersibles, and robots explore a massive underwater WWII archeological site. Airing June 10, 2015 at 9 pm on PBS Aired June 10, 2015 on PBS

- Originally aired 05.28.14

Program Description

Transcript

D-Day's Sunken Secrets

PBS Airdate: May 28, 2014

NARRATOR: Off the coast of France, an international team is exploring a hidden battlefield, looking for the secrets of how the greatest naval invasion in history unfolded. Buried here is a treasure trove of ships, tanks and potentially unexploded mines. These are the wrecks of D-Day.

June 6, 1944: For years, Hitler had devastated Europe, killing millions. Now was the time for the Allies to make their move.

CAPTAIN HENRY J. HENDRIX (Chief Historian, United States Navy): It was an all-out gamble. It was nothing less than the history of western civilization.

NARRATOR: But the odds were against them.

RICK ATKINSON (Author and Military Historian): It's hell. It's about as bad as combat can get.

NARRATOR: Three years in the making, this was the most epic struggle of the twentieth century.

ADRIAN LEWIS (Historian, United States Army Major, Retired): These are the men who made the difference. You should understand that.

NARRATOR: D-Day required the best minds in the military, working with scientists and engineers.

NICK HEWITT (Naval Historian): D-Day is the triumph of technology and engineering.

RALPH WILBANKS (Underwater Archaeologist): The guys that planned the logistics for this were unbelievable.

NARRATOR: New machines to break through Hitler's vicious defense; ingenious and untested ways to deliver an invading army.

TIM BECKETT (Consulting Engineer): I always knew it was big, but I think this really helps you see how big it was.

NARRATOR: Today's expedition investigates how the Allies tipped the odds in their favor…

ANDY SHERRELL (Sonar Team Director): Whoa, look at that.

NARRATOR: …and brings veterans back to the place where they nearly lost their lives.

ANDY SHERRELL: Bet you never thought you'd see that again.

NARRATOR: New technologies and veterans' memories come together to reveal this hallowed ground.

NICK HEWITT: The hidden battlefield is one of our most sacred charges.

NARRATOR: Right now on NOVA, D-Day's Sunken Secrets.

Along the north coast of France is the picturesque region of Normandy: charming villages; farms, with their patchwork of small fields; and beautiful beaches, where Parisians come for a holiday. But few realize that just beyond these tranquil beaches is evidence of the biggest and the most dangerous naval invasion of all time.

The violence of that battle still lives in the World War II wrecks that lie just off the coast. These wrecks tell the story of D-Day.

June 6, 1944: 7,000 warships, 11,000 airplanes, and 200,000 men, crossing at dawn, from England, to these beaches of Normandy, to liberate Europe from the Nazis.

Four years earlier, Hitler had conquered most of Europe, killing millions and setting up the most epic struggle of the twentieth century. All along the north coast of Europe, the Nazis had built a vicious wall of defenses to stop just such an invasion.

D-Day took three years to organize and was the Allied Forces best chance to retake Europe. But the odds were against them, and the future of the free world hung in the balance.

It has now been 70 years since this battle that changed history, but the magnitude of that invasion still inspires awe. How did the Allied Forces of Great Britain, the United States and Canada, depleted by years of war, manage to pull it off?

NICK HEWITT: One of the things we are learning is to treat the evidence of twentieth century battlefields as proper archaeology.

NARRATOR: Nick Hewitt, an historian at the National Museum of the Royal Navy, says that these D-Day wrecks can tell us things no official document can.

NICK HEWITT: The beauty of the D-Day underwater battlefield is the evidence is still there. It's all laid out for us. All we have to do is interpret the evidence to tell the story.

NARRATOR: What is the true story of this invasion?

It's referred to as D-Day, but what do these wrecks reveal about the invasion and how long it took to secure a foothold in Europe? And what tales do they tell us about the necessary engineering that made this all possible?

NICK HEWITT: D-Day is the triumph of technology and engineering. And what you see is specifically engineered solutions to specific problems.

NARRATOR: Buried here are inventions of scientists, engineers and even maverick businessmen, some of the unsung heroes drafted into this immense war effort.

These wrecks comprise one of the largest underwater archeological sites in the world. As the seventieth anniversary approaches, this site is beginning to get the closer examination it deserves.

To understand this hidden battlefield and these inventions, an international team of oceanographers, historians and archeologists has set out to examine the evidence buried here.

MAN ON BOAT: This is a new one?

ANDY SHERRELL: Yes, a new one, right off of Utah Beach.

NARRATOR: There are hundreds of ships, as well as tanks, guns, and potentially unexploded mines. The expedition team uses the latest in sonar technology, and even deep-water submarines to investigate the remains of this epic naval battle.

Undiscovered evidence is being charted and explored, like this American Sherman tank, one of the iconic weapons of World War II.

How did this weapon, intended for a land battle, end up here, intact and under water? It's mysteries like this that the expedition will investigate over the next six weeks.

SYLVAIN PASCAUD (D-Day Expedition Director): There are few areas in the world where you have so many wrecks concentrated in one area.

NARRATOR: Sylvain Pascaud, the director of the expedition, believes a systematic exploration of this “lost fleet” is necessary to give a true picture of what this battle really was.

NICK HEWITT: When we think of the D-Day landings, we think of a land battle. We think of great movies, we think of boots on the beach. But actually, 6th of June, 1944, was the biggest, most complex amphibious landing in history.

NARRATOR: The expedition starts with a sonar-equipped catamaran, named the Magic Star. On board is the latest generation sonar, submerged under water in the middle of the boat. Sonar uses sound waves, transmitted through the water, to image what is below on the ocean floor, like this British ship.

For a solid month, the Magic Star will sail back and forth in up to 40-mile stretches, each pass revealing long strips of this hidden battlefield. It's like mowing the lawn, a 200-square-mile lawn that is, with each pass, overlapping the last to make sure they don't miss a spot…

ANDY SHERRELL: Voila. Volia. Tres, tres bien.

NARRATOR: …or ship, on the ocean floor, below.

This survey phase will reveal potential targets for further investigation, like the mysterious sunken tank.

On board is Andy Sherrell who leads the team of sonar experts.ANDY SHERRELL: We collect one line of data at a time, but as you can see here, we are combing line by line by line. We are trying to build a very large underwater archeological map of the whole area.

NARRATOR: This area covers the site of the D-Day naval battle, where the Allied Forces, led by Britain, the United States and Canada, sought to regain a foothold in Europe.

Four years earlier, the Nazis had conquered France, along with much of Europe. Ever since, the Allied Forces had planned, in secret, how to fight back. They needed to win a toehold in France, and then could drive up to Berlin from the west. The Soviet Union would push in from the East, choking Hitler in the middle.

The stakes could not have been higher.

HENRY HENDRIX: What is at stake was nothing less than the history of western civilization. It was an all-out gamble. It was pushing all your poker chips onto the center of the table.

NARRATOR: Captain Henry J. Hendrix, the chief historian for the U.S. Navy, says what was involved in pulling off D-Day is hard to even imagine today.

HENRY HENDRIX: The Germans had, literally, years to prepare the defense of the beaches, so they are ready. They know, if Germany is to be defeated, the Allies must enter the continent somewhere, and the question is really, where?

NARRATOR: The options for the invasion were limited, and they had already tried unsuccessfully in other locations. Two years earlier, in France, the Allies tried to capture a port in a town named Dieppe.

That battle against the fortified German positions there was a disaster. More than 60 percent of Allied soldiers were killed or captured. This failure haunted British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and changed the course of the war.

In response to previous failures, President Roosevelt and Churchill met several times, in secret, to create a new strategy. The plan they devised was to overtake the region of Normandy from the Nazis. And the naval invasion was just the beginning.

The entire plan was codenamed “Operation Overlord.” It would be a surprise. The Nazis had expected an invasion at Calais, because it was so close and had a large port. Instead, the decision was to go further down the French coast, where there were no large ports, and target the beaches of Normandy with a massive amphibious landing, a much more difficult operation.

RICK ATKINSON: In an amphibious operation, generally, there's no middle ground. You either succeed or you don't. You get ashore and you move inland, or you get thrown back into the sea. Unlike most battles, where you can retreat and fight again the next day, you can't retreat in an amphibious operation.

HENRY HENDRIX: Overlord, in Normandy, is really the big gamble about whether democracy, as we know it, was going to continue and survive and grow and flourish and that people would be free, as we thought that they should be free, or whether Nazism and the atrocities that Hitler was committing, genocide, was going to succeed.

NARRATOR: In the end, five landing beaches were chosen, two American, one Canadian, and two British. They were given code names of Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno and Sword.

But even its chief architect wasn't sure it would work. The night before the invasion General Eisenhower wrote a letter taking the blame, if it failed.

LEE HAMILTON (Reading letter from General Dwight. D. Eisenhower): My decision to attack at this time and place was based upon the best information available. The troops, the air and the Navy did all that bravery and devotion to duty could do. If any blame or fault is attached to the attempt, it is mine alone.

NARRATOR: Perhaps the best way to understand why Eisenhower was so worried is to stand on Omaha Beach and see what the Allies were up against.

ADRIAN LEWIS: Omaha Beach is an excellent defensive location. If you're the Germans, what you want to be able to do is kill anything on the beach.

NARRATOR: Adrian Lewis, a former Army Ranger, is a history professor at the University of Kansas, and he has taught military strategy to West Point cadets.

ADRIAN LEWIS: The geographic formations here, the terrain, makes it excellent. From one end where the landing takes place, to the other end, is about four miles long.

NARRATOR: Lewis says any fighting strategy must begin with understanding the geography of the battlefield.

ADRIAN LEWIS: Omaha Beach is banana shaped. That banana shape is important. So instead of having your weapon systems pointing out to sea, what you would do is to actually have them pointing into the beach. So, if I put machine gun positions, artillery positions on this flank, more on this flank, instead of having them point out to sea, I'm actually having them pointing in, and that's what the German's did.

NARRATOR: This inward-pointing fire, or interlocking fields of fire, created a deadly kill zone on the beaches. This was a huge advantage for the Germans.

ADRIAN LEWIS: Excellent terrain for putting in a defense. As a matter of fact, if I were doing this thing, I'd rather be on the German side.

NARRATOR: In addition, the cliffs that surround the beach gave the Nazis the high ground. It seemed that nature gave them every advantage in this crucial battle.

HENRY HENDRIX: You're up against the weather; you're up against the tide; you're up against the beach. And when you are dealing with forces of that size, it is hard to get it done in the right way.

NARRATOR: This area off the coast is known for unreliable weather and some of the strongest ocean tides in the world. Those conditions are even difficult for today's expedition.

SYLVAIN PASCAUD: We've got three challenges: the weather, the tides and the current. I just cannot imagine 5,000 vessels, with 200,000 men, in conditions like that. If you disregard the weather, the current and the tide, you will be going absolutely nowhere.

NARRATOR: Ocean levels here can rise and fall up to 25 feet a day. The effects can easily be seen over the course of a few hours on the beaches.

Here, when the tide is out, the width of the beach increases—a full 300 yards wider at low tide! The significance of that is it meant the soldiers, on D-Day, would be exposed for much longer to the deadly Germany crossfire.

D-Day planners needed to understand every detail about the geography of this battlefield to plan for the assault. But how do you get that information when the entire country is under enemy control?

Evidence of the incredible effort to figure this out still exists at the United Kingdom Hydrographic Office, one of the world's leading producers of navigational charts. This building was an important intelligence site, it's location a state secret. In fact, the building was camouflaged to hide it from Nazi bombers.

Inside, top-secret documents still exist. Neptune was the codename for the Naval Operation.

These artifacts aren't quite like the sunken wrecks off the coast of Normandy, but they are important evidence of ways the D-Day planners found around the obstacles. An effort that began long before the invasion.

CHRIS HOWLETT (Cartographer and Marine Scientist): You have mines here, barbed wire entanglement here.

NARRATOR: Cartographer Chris Howlett explains that mapping the Normandy region was an extraordinary top-secret operation that required math, science and daring spy missions.

Low-flying aircraft were dispatched over the beaches. And surveillance photographs were taken at intervals throughout the day, documenting the changing tides.

CHRIS HOWLETT: These black lines are where the waterline was on different tides.

NARRATOR: Why was this useful? Using those different tide levels, mathematicians could calculate the exact slope of the different beaches, necessary to figure out what vehicles could be used.

Knowing every detail of the beach was crucial. At Dieppe, the Allies discovered only after landing, that their tanks could not get traction on the beaches there.

Every way of getting information was used. Even past vacation postcards were requested.

CHRIS HOWLETT: They put out a public request for the people of Britain: “Any postcards you collected in your holidays to France before the war, send them in to us and they may be of use.” And millions of postcards were sent in.

NARRATOR: These postcards gave essential information about what the coast of France, by now in enemy hands for four years, looked like. But not all the necessary information could be gleaned from a safe distance.

Just off the Nazi-controlled beaches lurks an X-craft. Inside this mini-submarine are five underwater spies.

NICK HEWITT: Perhaps one of the earliest phases of the battle was the survey and preparatory work carried out by men serving aboard miniature submarines, the X-craft, who were, effectively, secret agents.

NARRATOR: The X-craft were 50 feet long and barely five feet high. Some missions lasted two weeks in these cramped quarters. The surveillance gathered was used in making these maps, including some from the perspective of the sea, showing visible landmarks on the beach, like church steeples or houses. These were crucial for navigating the landings.

NICK HEWITT: They came up with a novel idea. The view at the bottom, here, is the view that you would expect to see if you were coming in from a landing craft at any given point along this map.

NARRATOR: Jim Booth was a member of this elite submarine force, venturing into mine-filled, Nazi-controlled waters, with barely any navigational guides.

JAMES BOOTH (Lieutenant, Royal Navy): Navigation, of course, was difficult, because then there were no SAT and air. A classic old-fashioned navigational trip: pencil and ruler and gyrocompass.

NARRATOR: Booth's mission was to go ahead of the invasion force and set up light beacons, so the huge armada of Allied ships would know where to go. His submarine was assigned to the British landing beach codenamed Sword, the furthest east of the five beaches.

He would be one of the first soldiers in action on D-Day. He was in position at 0100, military terminology for one a.m.

Today, Jim Booth has come back to Normandy to take part in the investigation. This is no leisurely retirement cruise. The D-Day expedition has brought in a team from Canada with two deep-water submarines.

NICK HEWITT: The veterans who stormed the beaches of Normandy are the most incredible people.

RICK ATKINSON: No one can bear witness with the same kind of emotional intensity that someone who was there can. We are losing 600 veterans every day. When they slip away they are in the shadows forever.

NARRATOR: For the first time in 70 years, Jim Booth will go under water off the coast of Normandy, just like he did for D-Day.

JAMES BOOTH'S DAUGHTER: There is a very small amount of worries, because he's 92.JAMES BOOTH: I haven't been in a submarine at all since then, no.

NICK HEWITT: I think you will find you can see a lot better from that one than you could in yours.

JAMES BOOTH: We had no windows, of course, at all.

NARRATOR: Ironically, this time the submarine is even smaller than the X-craft, but Jim Booth will only have to stay in the submarine for an hour, instead of the four days he did before D-Day.

Today's dive is in the exact same location off of Sword Beach. His shipmate is military historian Nick Hewitt.

NICK HEWITT: Any second now, you will be under water for the first time in 70 years. Here we go.

JAMES BOOTH: Look at that! It's reasonably clear today, too, isn't it?

NICK HEWITT: There's a shadow.

SUB PILOT: Roger. I've got visual.

NICK HEWITT: Jim's role, on the 6th of June, is to mark the safe channel through the enemy minefields. So, Jim has to go out with a small group of men, in advance of the landings, navigate themselves to exactly the right spot, surface alongside, we must remember, a minefield, and light a beacon so that the incoming ships can pass safely through.

NARRATOR: It was in this spot, off of Sword Beach, that Jim Booth placed the beacons on D-Day.

NICK HEWITT: Did you have an understanding of how enormous the scale of it all was?

JAMES BOOTH: Almost everyone was just a tiny cog in this vast wheel.

NARRATOR: His sub surrounded by mines, Booth and the X-craft crew had to find the exact location to set up the beacons. But with no lights on shore or radar, how did they do it?

JAMES BOOTH: It was very, very complicated. One must remember, all of the navigation aides had been switched off, because of security. We knew we were in France. It didn't take very long to recognize it was a church tower.

NARRATOR: In the end, Booth and his X-Craft crew navigated using the landmarks that had been mapped by the Hydrographic Department.

Booth says that it was the Allies attention to detail in the planning that made the difference, and that was a direct result of the lessons learned from the disaster at Dieppe.

JAMES BOOTH: Dieppe was really intended to be a test run for Normandy. It did all the things wrong. Those lessons were learned, and this was put into good force for Normandy.

NARRATOR: But the one thing the Allies couldn't control was the weather for the invasion, and the forecast did not look good.

By May, 1944, 2,000,000 soldiers were in southern England, waiting for the go-ahead from their commanders. And with 11,000 airplanes and 7,000 ships involved in this complicated operation, decent weather was required. But the science of weather prediction was not what it is today.

General Eisenhower and his Supreme Allied Command had only limited information, since satellites and weather radar wouldn't be invented until after the war.

Instead, weather data was collected at remote weather stations and sent to the U.K. Meteorological Office in Essex, England.

Records like these, dating back 150 years, are still archived here, including those for the D-Day landings.

These maps detailed weather patterns and were meticulously drawn to chart moving storm systems.

CHRIS TUBBS (Forecaster, U.K. Meteorological Office): These were the weather maps that they used for that process. The maps were produced every three hours, whereas now they would be done only every six or 12 hours.

NARRATOR: High and low pressure systems, the atmospheric conditions that determine the weather, were charted and analyzed at the headquarters.

CHRIS TUBBS: The low pressures are basically bad weather, strong winds, rain, a lot of clouds, the high pressures are mainly fine weather, with lack of clouds and quite warm temperatures, in June, anyway.

NARRATOR: At the center of the operation was Group Captain James M. Stagg. His responsibility was to track the weather data and report it directly to General Eisenhower. He kept a personal diary that is still held at the Meteorological Office. It shows the enormous pressure he was under.

The invasion was originally planned for June 5.

JAMES M. STAGG (U.S. Army/Excerpt from Diary read by Met Office Employee) Saturday, June the 3rd. Day of extreme strain, the weather situation got worse. Two depressions below 98 millibars at one in June. Who could have forecast this?CHRIS TUBBS: This map was from June the 3rd. And this is showing it typical, bad, early summer weather in the U.K.

NARRATOR: Before D-Day, there were several storms lined up.

CHRIS TUBBS: We've got a succession of low pressures across the chart. One here, one here, one to the northwest. This is going to keep the weather what we called “unsettled”: so clouds, rain, gale force winds in the Channel. Going to stir very rough seas. So anybody who is on a boat crossing the Channel would be in danger.

JAMES M. STAGG (Excerpt from Diary): Sunday June 4th, 1944. At 04:15 conference this morning assault for tomorrow definitely canceled.

NARRATOR: The bad weather would limit air support and create treacherous conditions for ships on the Channel. The invasion force is put on hold, but time is running out.

JAMES M. STAGG (Excerpt from Diary): Today, it began to appear that there might be a temporary fair interval Monday night. Should we advise to make use of it?

NARRATOR: The timing of the invasion had been selected to correspond with the lowest tide of the month.

This would give the Allies maximum time to unload men and equipment. With the tide low and coming in, ships can unload and be carried out to sea on the rising tide. If the tide were high and going out, boats would get stuck on the beach as the water receded.

HENRY HENDRIX: If you are on a ship that makes land at high tide and suddenly the tide is running out, you either need to leave then, or your ship is going to come and ground in the mudflats.

NARRATOR: Because of the changing tides, Eisenhower could only wait one more day. If the weather didn't clear, the invasion would have to be postponed for weeks.

JAMES M. STAGG (Excerpt from Diary): I'm now getting rather stunned. It is all a nightmare.

NARRATOR: Every day they waited, there was an increased chance that German intelligence would discover the huge invasion force poised at the coastline and realize that the invasion was coming. If discovered, the crucial element of surprise would be lost.

CHRIS TUBBS: This is the chart for Monday, June the 5th. This was the original D-Day. There was some crucial observations which made some of the meteorologists start to think that the 6th could be possible. And these operations were up here, in the north of the Atlantic. And, interestingly, they marked things on here that we don't nowadays, called “cols.”

NARRATOR: Cols are a gap, or interval of calm, that can exist between bad weather systems.

CHRIS TUBBS: Cols exist between areas of low pressure. And these were quite important for this situation, because they knew that if they could get into an area of a col the chances for getting the right weather for the landing were better. It wasn't a definite, but it was a possibility.

ADRIAN LEWIS: It's Eisenhower's decision. The momentum had already built up. I've got everybody locked and cocked ready to go. The fact that the weather was so bad…it actually made it one of his harder decisions.

JAMES M. STAGG (Excerpt from Diary): Monday, June the 5th, 1944. After one hour's rest, Met conference at 0300. Fair interval confirmed and invasion put on final and irrevocable decision. Whatever the outcome the decision is taken.

NARRATOR: Following this weather report from Stagg, General Eisenhower ordered the invasion to begin. Later he broadcast his blessings to the troops.

GENERAL DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER RECORDING: Soldiers, sailors, and airmen of the Expeditionary Force. You are about to embark upon the Great Crusade toward which we have striven these many months. The eyes of the world are upon you. Good luck and let us all beseech the blessing of Almighty God upon this great and noble undertaking.

NARRATOR: D-Day had begun, and there was no turning back. The armada of Allied ships left England and would sail through the night to the five different landing beaches.

NICK HEWITT: The scale of it is almost inconceivable: it's 7,000 ships.

RICK ATKINSON: And they include not only the ships that are carrying the infantrymen who are going to the beaches, but they include bombardment ships.

HENRY HENDRIX: Battleships after battleship, and destroyers.

RICK ATKINSON: All of those have to be launched from Britain. There's intense choreography that goes on. “You will go here. You will go there. You will go at this hour,” and so on.

HENRY HENDRIX: It was the most massive naval force that's ever assembled.

NICK HEWITT: D-Day is, without doubt, the single biggest, most complex amphibious landing in history.

ADRIAN LEWIS: The naval plan, Operation Neptune, encompasses 50 miles of beachfront and hundreds of thousands of soldiers, thousands of ships and landing craft. The magnitude of it is incredible.

NARRATOR: The landings were set for 0630, early the following morning. On the shores of Normandy, the Germans could only see the bad weather and thought that it would prevent any immediate invasion. They also did not see that, just off the coast, were a handful of small X-craft submarines. On board one was Jim Booth.

JAMES BOOTH: It was a hell of a time ago…69 years. It is very emotional, very, very emotional. It was, sort of, in the direction of the yacht, but where the last ripples are. That was the distance. We saw the soldiers playing football, here. That was the day before, actually. That was the day before. They didn't know what was coming.

NARRATOR: Off the coast, Jim Booth and the X-craft submarines were not alone. An 18-year-old, Robert Haga, from Virginia, was aboard the U.S.S. Chickadee, one of the ships that left England ahead of the armada to perform the essential task of clearing the Nazi underwater mines, an extremely dangerous operation.

ROBERT HAGA (Former Yeoman, U.S. Navy/Excerpt From Diary): June 5th, 1944, Underway for France.

NARRATOR: Haga kept a personal diary of these historic days.

ROBERT HAGA: The invasion will be early in the morning. We are to go in first and sweep a channel clear.

NARRATOR: The Germans had heavily mined the English Channel as part of their Atlantic Wall. Mines, in World War II, are like the I.E.D.s of today's wars in Iraq or Afghanistan: low-cost weapons, but highly lethal.

The Magic Star team has not found any unexploded German mines, so far, since they were largely cleared for safety after the war, but can the sonar reveal their effect?

CHARLES BRENNAN (Hydrographic Surveyor): This is pointed, up here, and looks like a bow.

ANDY SHERRELL: I think it hit a mine.

NARRATOR: They come across a Canadian ship, called the Fort Norfolk. Its bow was broken off by a mine.

ANDY SHERRELL: That is unbelievable.

CHARLES BRENNAN: That is a gorgeous, gorgeous wreck.

NARRATOR: One mine can have a disproportionately large impact, sinking a whole ship full of soldiers and equipment.

NICK HEWITT: The important thing about all naval warfare, the equipment or the men contained in it are an awful lot easier to destroy at sea than they are once they've got ashore. A single mine could drown all those men and destroy all their equipment. It would take days of fighting to do the same job on land.

NARRATOR: One place you can safely see some of these mines and other military hardware is the Museum of Normandy Wrecks, in a little town called Port en Bessin. It is a private collection of D-Day military equipment salvaged off the coast here.

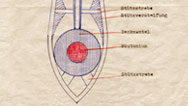

Axel Niestle, an expert on the German military, says the Nazis used four different kinds of mines in the ocean off Normandy. The most common was a contact mine.

AXEL NIESTLE (German Military Historian): The whole body is filled with explosives. Once it goes up close to the ship, it can take a battleship.

NARRATOR: These mines were anchored to the ocean floor and floated just below the water's surface. The horns are detonators, something like a very large off/on switch.

AXEL NIESTLE: And once the ship hits one of these detonators here, a chemical reaction is started, the detonator is ignited, which is a primer, then the full charge is going off.

NARRATOR: The Nazi's had heavily mined the bay just off the beaches, and, so, the Allies had to sweep lanes clear just before the landings.

NICK HEWITT: It's very, very dangerous work. As one veteran described to me years ago, everyone is walking, kind of, half-crouched, in anticipation of an explosion.

HENRY HENDRIX: We waited until the last instance. Minesweeping tells you where the landing is going to occur. If you begin too early, then you have already tipped them off on where the operation will be focused and concentrated.

NARRATOR: Haga's boat was third in a line in the minesweeping operation off of Omaha Beach, next to the U.S.S. Osprey.

ROBERT HAGA (Diary Excerpt): At 1800, the U.S.S. Osprey was hit by a mine.

ROBERT HAGA: I was on the bow of the ship. And when it hit, the ship just lifted out of the water and exploded. This mine hit the magazine that carried all the ammunition in the ship.

NARRATOR: Six men on the Osprey were killed in the initial blast. These were the first casualties of D-Day.

ROBERT HAGA: A lot of the crewmen and officers were blown out into the water and they were badly burned. We were throwing ladders, rope ladders, as fast as we could, but they couldn't see. So we were having to, sometimes, hook onto each other to pull them up. And the skin would come off their arms. I still have bad memories about that.

NARRATOR: Haga has returned to Normandy as part of the expedition and wanted to see the newly installed Navy Memorial at Utah Beach that honors many of his fellow minesweepers.

The minesweeping operation went on in view of the German-controlled beaches in the hours leading up to the invasion. Everyone was haunted by the possibility that the soldiers there would sound the alarm. But that never happened, perhaps because, as part of Operation Overlord, the Allies made a massive effort to mislead Hitler into thinking that the invasion would be further north, along the coast near Calais.

Fleets of fake military gear were positioned in England, across from Calais, and an extensive counter-intelligence campaign was organized to deceive the Nazis.

RICK ATKINSON: It's one of the most brilliant deceptions in the history of warfare. It's right up there with the Trojan horse.

NARRATOR: Not the Trojan horse, but, on the night before the invasion, another wood vehicle was slipping behind enemy lines, unnoticed, under the cover of darkness.

There are two large rivers that cross the road between Normandy and Paris, the Caen Canal and the Orne River. The Allies realized they needed to capture these bridges and other strategic targets before the landings or risk getting trapped on the beaches.

It was urgent to get men behind enemy lines and secure these targets. But how do you do that without modern Apache helicopters? One possibility was dropping paratroopers, but loud airplanes could alert the Germans, giving them time to blow up the bridges. So instead, the job fell to men like Kermit Swanson, a farm boy from Minnesota, who was trained to fly a silent wood glider behind enemy lines.

KERMIT SWANSON (Former Glider pilot, U.S. Air Force: Our mission was to fly that glider over there and land and try to keep from killing ourselves. If we did that, we completed most of our objective.

NARRATOR: The objective was made more dangerous by the landscape of Normandy. This farming region is known for its patchwork of small fields, with fences formed out of a dense hedge of rocks and trees. The plan was to land in the cover of darkness, and those hedges would not be visible.

KERMIT SWANSON: You couldn't see, because it was dark.

NARRATOR: The gliders could carry 12 men or even a jeep, land, and jump right into action, if they landed safely. These planes were made of wood and fabric, with a thin metal frame, and would easily break apart if they hit an obstacle.

DON PATTON (Colonel, U.S. Army, Retired): It was terribly dangerous to fly a glider. It was dark, it was overcast, you were having to land into the little small fields. I don't think anyone would want to be going 90 miles an hour and crash into a tree with only plywood as a barrier.

NARRATOR: The commander for Allied air forces predicted, in a letter to General Eisenhower, that the gliders could suffer casualties of up to 70 percent on D-Day.

The plan was to tow them across the English Channel, with C-47 planes, just after midnight. When they reached the drop zone, their towrope would be cut. Then the pilots had about three minutes before they had to land, no matter what obstacles were in their way.

KERMIT SWANSON: You are traveling at about 80 miles an hour. Now, you make a turn, downwind, and you've got three minutes and the wheels are going to be on the ground—probably got three minutes of your life left.

NARRATOR: Swanson, now 94 years old, says that it was the last 30 feet of the descent that was the most dangerous, because you might hit a tree.

KERMIT SWANSON: I must have been 20, 30 feet off the ground. I didn't even see the tree, and I hit the ground, like that, and that took the wheels off. And then you slid until you stopped. And everything got perfectly quiet and perfectly black, and I said, “Anybody hurt?” The guys behind me said “nobody back here.” And about that time a cow bellowed real loud, real loud. I said, “Now you know where you're at.” We were in the pasture.

NARRATOR: Once on the ground, these troops moved into position to take the strategic targets.

RICK ATKINSON: What you are trying to do with these troops is trying to prevent the Germans from counterattacking in your flanks, before you have got enough combat power coming ashore to repel these attacks.

NARRATOR: The glider operation went better than expected, with less loss of life than predicted. The troops took control of the strategic targets without alerting the German command.

Along with the gliders, 13,000 paratroopers were dropped into France, with a mission to disrupt the German defenses. These men were the very first Allied soldiers to touch French soil on the morning of D-Day.

Back at sea, the armada of ships was approaching the coastline, behind the minesweepers, with Robert Haga aboard.

Jim Booth and X-craft crews were at work, setting up the beacons.

The next obstacle was getting 150,000 troops on shore, something that the Nazis had spent years making sure would not happen.

ADRIAN LEWIS: The Germans were good engineers. They knew how to build bunkers, I tell you. The thickness is from there to about here.

NARRATOR: Ever since invading Europe, the Germans worked to build massive fortification all along the north coast of Europe, including 15,000 bunkers overlooking the beaches.

ADRIAN LEWIS: Just take a look at this. You can see the entire beach, and if you can see something, you can destroy it.

NARRATOR: At this point in the war, the Germans knew their troops were stretched thin, so defending their hold on the beaches was essential to their strategy.

ADRIAN LEWIS: Defense is the stronger form of war. If your defense is well done, if you have enough obstacles, enough mine fields, enough firepower, you can reduce the number of troops you need.

NARRATOR: Along the coast of France, these bunkers held powerful guns that could shoot 20 miles.

And the beaches were covered with a series of mined obstacles, hidden just below high tide, that would destroy any ship that tried to land, including the famous hedgehog: crosses of steel that could rip open the bottom of a ship.

All of this was part of one the most fearsome military fortifications ever built. It was known as Hitler's Atlantic Wall.

ADRIAN LEWIS: The Atlantic Wall was strong, and it was getting stronger day by day.

RICK ATKINSON: In the six months before June 6, Hitler allowed almost unlimited resources to be poured into it. The German forces had almost doubled. So, it's pretty serious.

NARRATOR: One of Hitler's top generals, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel was sent to the front, by Hitler himself, to fortify this powerful death trap.

The beach obstacles dictated a terrible choice to the Allies. Do you land at high tide, so your soldiers spend less time on the beach exposed to enemy fire, or do you land at low tide to protect the ships from these obstacles?

HENRY HENDRIX: Operation Overlord runs on the back of ships, so the men are coming, the tanks are coming, the supplies are coming. And so it's important that the ships to survive. It's all to preserve the logistic ships, because those are the irreplaceable items of Operation Neptune. Without them Neptune fails.

NARRATOR: General Rommel knew that landing at high tide would offer the shortest run to safety for the soldiers. At high tide, these deadly defenses would be hidden. But the decision had been made to land at low tide. The ships would be protected from the deadly hedgehogs, but how do you protect your soldiers?

The answer would come from an unlikely place, a town better known for music than the military: New Orleans.

Andrew Jackson Higgins was a colorful local boat builder who believed he had the solution for the Navy. He already had a boat, called the Eureka, that was built to navigate the shallow waters of the Mississippi River, not Rommel's deadly mines, but the logs and sandbars here, so why not use them for beach landings?

The Navy was skeptical. It seems Higgins didn't always follow military protocol.

JERRY STRAHAN (Author and Higgins Biographer): As the Depression was going on, business was bad, and then he started building boats for rum runners. Then he went to the Coast Guard and said, “I don't know if you noticed it, but the opposition has a lot better and quicker boats.” And then he would build faster boats for the Coast Guard. Then he would go back to the rum runners and say, “The Coast Guard has newer vessels. We need to build you something a little faster.” So he did play both sides of the fence.

NARRATOR: Today, at the National World War II Museum, in New Orleans, they are working rebuild some of Higgins' famous boats.

Tom Czekanski, the chief curator at the museum, is an expert in military hardware. He says, to understand what makes the Higgins boat work, you have to look under one, to see the unique engineering of the hull.

TOM CZEKANSKI (Curator, National WWII Museum): The important thing here is that the hull churns up the water at the front, gets lots of air in it. If you got water and air mixed together, that's getting the boat up just that little bit more. That gets you onto the beach.

NARRATOR: At the back of the boat, there was a specially designed metal structure that ran below the propeller to protect it when the boat ran aground.

ANDREW JACKSON HIGGINS (Film Clip): Bring the boats on in and damn the obstacles.

NARRATOR: The Eureka boat was designed for unloading cargo over the sides of the boat, like illegal liquor. But the Navy's cargo of soldier would need to climb over the sides, making them vulnerable to enemy fire.

Was there a way to get the men out faster?

Naval engineers had seen Japanese boats with front-loading ramps, but no one knew how to build them. And so they asked Higgins to draw up some plans.

JERRY STRAHAN: The Navy had been trying it for over two decades, had been unsuccessful. They wanted drawings. Higgins said, “Drawings, hell. You be here in three days, and I'll have one in the water,” which he did.

NARRATOR: Without a ramp, it took 57 seconds to unload troops; with a ramp it took only 19 seconds.

ANDREW JACKSON HIGGINS (Film Clip): They could land quicker, exposed for a shorter time to enemy fire.

JERRY STRAHAN: Which saves you 38 seconds from being shot at on an open beach, which saved incredible numbers of lives.

NARRATOR: Adolph Hitler knew of Higgins' famous boat and is said to have called him the “new American Noah.”

Not unexpectedly, the sonar operators are unable to find any of these wooden boats. It would have been difficult for them to survive the strong currents of the English Channel for 70 years. But there were many other landing craft made of metal, which did survive. And they come in all shapes and sizes.

RALPH WILBANKS: All of these wrecks are just out here, and you don't know it. If you could drain this, people would go “God, look at all of that.” But you can't.

NARRATOR: In World War II, there were dozens of different kinds of landing craft, all engineered for specific tasks. The famous Higgins boat carried soldiers, called personnel, or possibly a jeep, so the boat was labeled Landing Craft, Vehicle, Personnel, or L.C.V.P.

There were landing crafts with powerful guns, appropriately called landing craft gun, or L.C.G.

The list went on: L.C.I, for infantry; L.C.M. for mechanized, L.C.R. for rockets. And there was a whole class of larger ships, like the L.S.T., or Landing Ship Tank.

RALPH WILBANKS: I can't even imagine. We're sitting here looking at something and trying to decide whether it's an L.S.M. or an L.S.T. or an L.S.V.P. There's this massive amounts of L.S.s. The guys that planned the logistics for this were unbelievable.

NARRATOR: Today the sonar team sees the signal of an enormous ship, longer than a football field.

ANDY SHERRELL: All right.

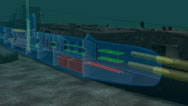

NARRATOR: Even though the ship is buried beneath 100 feet of water, this new multi-beam sonar is accurate within half an inch. Millions of sonar points are detected and then translated into a three-dimensional image that reveals intricate details of the engineering.

ANDY SHERRELL: We'll go by it again.

…busted up.

NARRATOR: This level of visualization allows the team to make precise measurements that help identify the ships. They make out what looks like a bow door and what the sonar team thinks is a vehicle, still on the ship's deck.

These features help them identify the type of ship, which they can cross reference with a military manual.

The ship they've discovered today is an L.S.T., a Landing Ship, Tank, the workhorse of the Allied naval forces. L.S.T.s were some of the largest landing vessels in the fleet and played an essential role in the D-Day invasion. They addressed one of the biggest problems created by the new amphibious landing strategy: how do you get all the gear the army needs onto the land?

ADRIAN LEWIS: One of the ways to look at an amphibious assault is that it's a race. The race starts the minute you hit the beach there, and it's a race for buildup. Who can build up the most forces the fastest?

HENRY HENDRIX: In World War II, tank warfare dominates, so you are bringing a lot of tanks across the Channel. They're not flown in, they can't drive there. So tanks, jeeps, other vehicles had to be brought by ships.

NICK HEWITT: You don't need a port to use an L.S.T. These are the chess pieces that get moved around that global board. And they are probably the single most important type of ship used in assault landings anywhere in the Second World War, massively important piece of technology.

NARRATOR: The U.S. manufactured so many of these L.S.T.s, they didn't even bother to give each ship a name, just a number.

HENRY HENDRIX: These ships were built in the United States and then sent to England, hundreds of them. We had to change virtually every bridge on the Ohio River and on the Mississippi to allow these combatant ships to make it back to the ocean. And we did it, and we did it very rapidly.

TOM CZEKANSKI: One of the key elements in our technology was our ability to build overwhelming numbers. That production was an amazing factor in our victory over Nazi Europe and Japan.

ADRIAN LEWIS: The engineering is not all that miraculous but the, production, American production, American capacity to produce volumes is what made the difference. We could produce 50 to their 10. We win.

NARRATOR: On the morning of D-Day these L.S.T.s ferried men across the English Channel. But they were too big to land before the German defenses had been cleared. That's where the Higgins boats came in.

NICK HEWITT: In the early assault phases, you don't want to put all your eggs in one basket. You don't want to put one big vulnerable ship on the beach. So, you have the famous Higgins boat and the British equivalent, which was small craft, capable of carrying 30 men who could get into action immediately. And to be really crude about it, if you lose one, it's not the end of the operation; it's 30 guys, not 800.

NARRATOR: This landing chart shows where the large ships, like the L.S.T.s, pulled up on the morning of D-Day, 11 miles off shore. Then there are smaller paths into the beach for the landing craft, like Higgins boats.

For Ralph Wilbanks, mapping these wrecks on the ocean floor is more than just sonar science. His father fought in the Pacific, which makes these two-dimensional images really come alive.

RALPH WILBANKS: These boats that are blown up and pieces missing from them…and even when they dived on it the other day, they had big holes in it. You could see where something happened, violent, to cause that boat to go to the bottom, which had to have been really catastrophic for the crew that was on the boat when it happened. That's the reason they were the greatest generation.

NARRATOR: It is very present to you, even today?

RALPH WILBANKS: Yeah, tough place.

NARRATOR: And as dawn broke on D-Day, it was about to get a lot tougher. The massive fleet appeared just off the German beaches, a scene made famous in the 1962 film The Longest Day.

HENRY HENDRIX: If you've seen that classic scene in The Longest Day, when the German is in the pillbox, and the morning mist begins to lift, and then, stretched out in front of him, from as far on the, you know, from the east to as far on the west as he can see, are ships, and they're emerging out of that fog. It was the most massive naval force that's ever been assembled.

NARRATOR: At 0530, it was time for the Allies to bring out their biggest guns, and the naval bombardment began.

HENRY HENDRIX: You have to imagine battleship standing maybe a mile, two miles off shore.

RICK ATKINSON: This is going to happen right around sunrise, because you can see what you are shooting at.

HENRY HENDRIX: So, you are hurling these large bunker penetrating projectiles, about the weight of a Volkswagen. It's tremendously loud. It's loud unlike anything you can possibly imagine. The smell, the smell of cordite burning, of gunpowder burning is something you won't forget.

NARRATOR: The Air Force bombers also joined in.

RICK ATKINSON: The Americans had made the decision they were going to have a very truncated naval preparatory fire. It only lasted 35 minutes. If you were invading an island in the South Pacific, sometimes the bombardment would last for days, but because we were invading an area where the enemy can reinforce quickly, the decision was made to do it quickly. Let's try to get on the beaches quickly. The British preparatory gunfire lasted closer to two hours. I think the British were right, as it turned out.

The Channel was full of boats. The pillboxes were back up on the cliffs, and they were firing continuously.

NARRATOR: Bill Allen was on an L.S.T., bringing soldiers into Omaha Beach, and remembers this brutal start to the day.

BILL ALLEN (Former Corpsman, U.S. Navy, L.S.T. 523): I remember all the firing, the noise, all the disasters and death. You'd see someone who had been killed, floating on the water.

NARRATOR: Allen was a medic, with an overwhelmingly difficult assignment.

BILL ALLEN: I was on the death detail. Started bringing casualties out to us, and we loaded casualties over the side of the ship. By the time we would get them, they'd be dead. But we'd clean them up the best we could. Identify them, to the fact put the dog tags…and you tried not to really dwell on it, I guess.

NARRATOR: Painful memories like these prevented Allen from talking about his D-Day experiences until recently, but today, he has come back to Normandy, for the first time since 1944.

He is once again on a ship off the coast of Normandy. This time he isn't tending to casualties, but instead he has brought his wife, Idalee, two daughters and two of his of grandchildren.

BILL ALLEN: When I was here before, everything was so confused and noisy. Now it's so calm and peaceful. It is hard to realize the difference between the two.

NARRATOR: Allen's L.S.T. delivered men into Omaha Beach on the morning of D-Day. Then, on their fourth trip into the beaches, they hit a mine and the boat sank. Today the sonar crew can show Bill just what happened to it.

SONAR CREW MEMBER: Oh, look, here comes something. There's the stern.

BILL ALLEN: Boy, that is something.

CHARLES BRENNAN: I have been doing multi-beam survey work for over 25 years. When we had Bill, the veteran, on, as soon as he saw that image, his story, his memories came back. It was a way I had never seen multi-beam data before,…

ANDY SHERRELL: Look at that big hole there. You think that's from the mine?

BILL ALLEN: Far as I know, it almost had to be.

CHARLES BRENNAN: …because he could see, fully, the vessel that was blown out from under him, on the seafloor.

BILL ALLEN: You had a galley, down below, that's where we ate.

CHARLES BRENNAN: It was the first time I felt the multi-beam data had a soul.

NARRATOR: After 70 years of holding back his World War II memories, Bill Allen, now, at 88, is brave enough, not only to return, but to go down in the small submarine to see the ship he was on when it sank.

SUB PILOT: Okay Bill, I'm going to get in the sub first. I'm going to get myself into the pilot seat. Then we have a ladder that we are doing to drop down in.

PATTY LEE ALLEN (Bill Allen's Daughter): Not to brag on him, but I can't think of too many 88-year-old men who would go down to where they almost lost their lives and revisit it and be excited about it, like he is.

NICK HEWITT: One of the most important aspects of looking at this now, and not waiting any longer, is that we still have veterans with us. We can still hear the testimony of those who were there while we investigate the battlefield they fought on. If we wait any longer, there simply won't be any left.

NARRATOR: The details of that horrific day slowly come back during his dive with sonar expert Andy Sherrell.

ANDY SHERRELL: Hard to believe huh?

BILL ALLEN: Boy, I tell you.

ANDY SHERRELL: Want to try to find the bow?

BILL ALLEN: I'd like to see it.

ANDY SHERRELL: I'd like to see it, too.

BILL ALLEN: We made three trips in, successfully, and started on our fourth trip.

ANDY SHERRELL: How old were you?

BILL ALLEN: I was just barely 19. I had finished lunch and come out on the topside, and it was about one o'clock.

I don't even know how to describe the noise it made…that it made. It sort of reminded me of when you step on a banana peel and you know how you're flip-flopping? You know you're going to hit the ground, sooner or later.

NARRATOR: L.S.T. 523 was sailing in rough waters, when it came down mid-ship, directly on a German mine. Allen was at the bow of the ship, in front of where the mine exploded.

BILL ALLEN: It just blew the ship completely in half.

ANDY SHERRELL: And it happened so quick?

BILL ALLEN: Yep. A real state of panic. Everyone began to jump off.

NARRATOR: On today's dive, Allen wants to see where that mine hit. And it doesn't take long before the expedition's submarine is right on top of it.

SUB PILOT: We are on the wreck. Over.

NARRATOR: This is all that remains of the L.S.T. 523, a rusting hulk of metal, overgrown with barnacles and algae. They can barely make out a tank on its surface.

ANDY SHERRELL: Bet you never thought you'd see that again?

NARRATOR: The explosion tore through the ship, and the bow that Allen was on was sinking. Everyone began to jump off.

BILL ALLEN: I knew I wasn't too good a swimmer, but I knew that something had to be done pretty quick, because our bow was going down. What it boiled down to was which way I wanted to drown. Did I want to go down with the bow or did I want to drown swimming?

NARRATOR: Just at that moment, Allen saw a life raft, with a medic he knew from Mississippi.

BILL ALLEN: And he hollered at me, “You can't swim out here. Stay there. I believe I can get in there to you.”

He got within, oh, I guess, 12 to 15 feet of me, and I said, “I can jump that far. I know I can.” And I took off, and I made it. We both had just one arm over the raft. We picked up four more army personnel.NARRATOR: Allen and the others were saved when a passing ship spotted their raft and pulled them to safety.

BILL ALLEN: Every time you close your eyes you just reliving the same thing, a blast, and seeing those same sights. Sometime after midnight, I rolled over, and Jack said, “Bill, have you been to sleep yet?” I said, “Jack, I don't think I'll ever go to sleep.”

NARRATOR: They say farewell to the 523.

SUB PILOT: We're coming up. Saying farewell to the 523.

BILL ALLEN: On the ship, we had a compliment of 145; the final count: 28 of us got off, 117 was killed or lost.

NARRATOR: For Bill Allen, another powerful way to reflect on his time during D-Day was taking his wife and family to the American cemetery that overlooks Omaha beach.

BARBARA (Bill Allen's Daughter): Daddy, what's the name you are looking for? Stabil?

IDALEE ALLEN (Bill Allen's Wife): It's just never-ending.

NARRATOR: There are more than 9,000 American soldiers buried here. One of them was Allen's commanding officer, Vito Stabil, a young doctor just out of medical school.

BILL ALLEN: He was an officer, and the rest of us were enlisted men, but we were all shipmates. There wasn't that much distinction between us. He had a great life ahead of him, but it got stopped. But I appreciate being able to come to his grave, very much.

ADRIAN LEWIS (Historian): In World War II, 70-million people are killed, 70-million people. It is the most significant event in the twentieth century, bar none. Nothing comes close to it in terms of shaping the world that we live in. And so, when you stand at that cemetery, these are the men who made the difference. These are the men who did more to shape the world that you live in right now than anybody else. And you should understand that.

NARRATOR: The loss of life weighed heavily on D-Day planners. Minimizing casualties was a solemn duty and strategically essential.

One way to reduce casualties on the beach would be to make sure the bunkers of the Atlantic Wall were taken out before the infantry landed. But doing so would prove to be one of the biggest challenges on D-Day.

The naval and Air Force bombing just before the landings were the first steps to dismantle the bunkers, but then the guys on the beach also needed to have the big firepower of tanks.

ADRIAN LEWIS: One of the attributes of the tank is firepower. Main gun of a tank can destroy bunkers, machine gun positions. It can penetrate some of the concrete positions. Small arms fire, even machine gun fire from infantry will not do that.

NARRATOR: The Allies had tried to put tanks in landing craft at the battle for Dieppe, but the process of unloading made them sitting ducks and contributed to the slaughter. So, for D-Day the Allies needed to figure out how to get the tanks to the beach quickly without putting them in boats. So the engineering question was, “Can you turn a tank into a boat?”

Nicholas Straussler specialized in engineering military equipment in England. He had emigrated from Hungary, now under Nazi control.

Straussler took inspiration from the ancient Greeks. Archimedes discovered that any object could float if it displaced enough water to offset the volume that's submerged. Archimedes' principle was engineered into Straussler's design. By deploying an inflatable skirt that came up on the sides of the tank, about four feet, it turned the tank into a rather poorly designed, but adequately floating boat, at least in calm waters.

You can see how Straussler pulled off his design on this tank, retooled by Bob Gundy, a military vehicle expert. There is a framework made up of inflatable support tubes that are then wrapped by a canvas skirt. They were called Duplex Drive tanks, or D.D. tanks.

With the push of a lever, the support tubes deflate, and the skirt would drop, so the tank was ready to roll into action.

These floating D.D. tanks were to hit the beaches five minutes before the troops went ashore. But on the morning of the invasion, the seas were dangerously rough, with swells recorded at six feet high. When the tanks off Omaha Beach were launched, they immediately started to sink: wave after wave.

ADRIAN LEWIS: Let's say you are one of these guys in the D.D. tank. Put yourself in the place of those guys, four of them in the L.C.T. First one goes off into the water and immediately starts to sink in; and the second one rolls off into the water, and it starts to sink. You are the third guy; what are you going to do? I don't know. You ask yourself, why?

RICK ATKINSON: It's pretty hard to understand 70 years later. It was pretty hard to understand then. These were their orders. It was critical to get these tanks ashore. Even though you saw that the guys in front of you were having trouble and, in some cases, gone under, they kept pushing.

NARRATOR: There is a mystery about just how many D.D. tanks are still buried under water. The definitive answer will come from the expedition's comprehensive sonar survey.

SUB: Once we close the hatch, the submersible is pressure proof.

ADRIAN LEWIS: I am a retired soldier; I spent 20 years in the army. I haven't done much with the Navy, so going down in the sub was a unique experience for me.

SYLVAIN PASCAUD: Okay, Adrian. Time to go.

NARRATOR: Today, Adrian Lewis and Andy Sherrell are going down in the submarine off Omaha Beach, to investigate what happened to the D.D. tanks. Sherrell has located a group of tanks, not far apart.

ANDY SHERRELL: We have the bottom in sight. Tanks over there.

NARRATOR: Two battalions of 32 D.D. tanks were supposed to lead the way onto Omaha Beach.

ADRIAN LEWIS: Most of them are gone now.

NARRATOR: Without them, the infantry would inevitably suffer from an unrelenting German attack.

ADRIAN LEWIS: There we go. You can see the main gun now. That's it.

NARRATOR: The water in the English Channel is so murky, it is only with the help of sonar coordinates that Sherrell and Lewis finally locate one of the lost D.D. tanks.

ADRIAN LEWIS: You don't see the skirt any more, though.

ANDY SHERRELL: No, right around that edge, though.

ADRIAN LEWIS: Right. That would have deteriorated, gone away.

When we first saw the D.D. tank, I didn't recognize it.ANDY SHERRELL: That's pretty cool, huh?

NARRATOR: These swimming tanks were not engineered for the six-foot swells they found on D-Day. In all, 27 tanks sank off of Omaha Beach.

ADRIAN LEWIS: Looks like the hatch is open. One of the front hatches is open. Which would make sense, so they could get out.

My first thought is: the men in this tank, soldiers in this tank, who they were and did they get out? Those tanks are burial places essentially. You have to keep that mind.

NARRATOR: Despite the loss of tanks, the Higgins boats, full of soldiers, arrived on the beaches right on time. But the battlefield they faced was not what they were expecting.

RICK ATKINSON: If you're an infantryman on Omaha Beach at 7:30 in the morning, you're really sorry you don't have more armor with you. Because it's hell. It's awful. It's about as bad as combat can get. And there are men by the dozens, then by the hundreds, who are being slaughtered all around you. And so, the fact that you don't have the protection of a 33-ton Sherman tank next to you, firing back at that pillbox over there or firing at that machine gun over…nest over there, all you've got is your rifle, means that you've got a difficult row to hoe for the next several hours.

NARRATOR: Combat engineers trained with explosives to blow up beach obstacles like mines and hedgehogs, landed in the first wave.

RICK ATKINSON: The job of those engineers was to blow gaps in these defenses. They were to blow 12 gaps on Omaha Beach. About half of all those combat engineers were killed, wounded or missing.

NARRATOR: Along with the floating tanks, the plan had counted on Air Force and naval bombings to take out the German bunkers. But it did not work, and, so, the men on the beach faced the Germans alone.

ADRIAN LEWIS: I've made the argument that the generals failed. The generals failed. The plan did not work at Omaha Beach. This is why the cost was so high in terms of American lives, in terms of numbers of soldiers killed, because they had to generate the combat power necessary to get over the bluff there at Omaha Beach.

RICK ATKINSON: No, there was no failure; in fact, the failure is entirely on the side of the Germans. Omaha was a lot harder than they thought it was going to be, but look, the Germans had four years to build the Atlantic Wall. It took less than four hours to crack the Atlantic Wall, including at Omaha Beach. Once those initial soldiers scaled the bluffs at the back of the beach, and they're up on the escarpment, even though the war is not over, the battle of Normandy has hardly been won, the Atlantic Wall has been cracked.

NARRATOR: Wave after wave of infantry kept coming. By 12 noon, after several hours of brutal fighting, the first Americans had fought their way onto the bluffs overlooking Omaha Beach.

The cost of that victory was very high. Even today, there is confusion among experts as to the total casualties, with estimates ranging from two- to more than four-thousand in the battle for Omaha.

The landings at the other four Allied beaches went more smoothly, with far fewer deaths, although they were not without significant valor and casualties.

It is argued that one reason things might have gone better on the British beaches were a group of inventions that the American army decided not to use.

Ian Hammerton, a tank driver on Sword Beach, still has the landing map from the Hydrographic Department that he carried in his pocket on D-Day.

IAN HAMMERTON: It suffered a bit from seawater, but that's top secret.

NARRATOR: Hammerton's unit is famous because of its leader, Major General Sir Percy Hobart.

IAN HAMMERTON: He was an innovative character who wouldn't take “no” for an answer.

NARRATOR: Hobart was known as a brilliant but eccentric character, who Churchill specifically called back into service for the preparation of D-Day. His unit was known as Hobart's Circus.

IAN HAMMERTON: Hobart's Circus it was called, because from time to time, all sorts of ideas were dreamed up for dealing with situations, and we acquired all sorts of strange equipment.

NARRATOR: Hobart's goal was to engineer a way around the Nazi's deadly obstacles. One of his most famous inventions was the flail tank, used to clear mines.

IAN HAMMERTON: This is a model of a flail tank, made by my son.

NARRATOR: Ian Hammerton, who piloted one of the flail tanks on D-Day, shows how it worked.

IAN HAMMERTON: It is an ordinary Sherman tank, but it has this apparatus on the front. The chains on the front would spin around on this drum and thwack into the ground. They're like this. That's a part of a chain that got blown off.

RICK ATKINSON: The British actually have a more inventive approach in some cases. Americans have the attitude, “We don't really need those on our beaches; it complicates our training.” And there's a bit of a “not-invented here” attitude. These are British gadgets; let the British play with them.

NARRATOR: Hobart's engineers invented all sorts of clever ways of overcoming the German obstacles, which became known as Hobart's Funnies, though their purpose was anything but that: flame throwers, for incinerating anyone inside the concrete bunkers; devices to fill anti-tank ditches or create an instant bridge.

On June 6, Ian Hammerton's flail did successfully break through the defenses at Sword Beach and help clear the terror mines.

Bill Allen's L.S.T. 523 unloaded men bound for Omaha Beach in the morning, and that afternoon, they began to receive the casualties.

And Robert Haga, the minesweeper, kept working to clear the lanes through the German underwater minefield.

By nightfall, on June 6, 1944, all five landing beaches were under Allied control. Determining the exact cost in lives lost is difficult, but it is estimated that there were at least 10,000 casualties, including 2,500 deaths.

But more death and destruction was yet to come, as the D-Day expedition will reveal.

The goal of Operation Overlord, the D-Day invasion, was not just to gain a foothold in Europe, it was to secure all of Normandy and ultimately drive through to Berlin.

Carver McGriff, who landed on the other U.S. beach, Utah, says, to understand the difficulty of fighting in Normandy, you need to walk around the small farms that lie just off the coast here.

E. CARVER MCGRIFF (Former Private First Class, U.S. Army 90th Infantry Division): Imagine you're a young second lieutenant, leading 25 kids like me, and your job is to take the next hedgerow: what do you do?

NARRATOR: Despite all the years of planning for the invasion, the Allies were not prepared for the obstacles they would face in the battles here.

The problem was easy to overlook. It was the ancient fences, which surround farms in Normandy, called hedgerows. They seemed so unassuming.

One aerial photograph of eight square miles revealed nearly 4,000 small fields.

RICK ATKINSON: There's a kind of terrain known as the hedgerow country. These are fields that have basically turned into mini-fortresses. The French have been farming that area for a millennium and every farmer has been clearing the land by pushing the rocks and debris and trees and what not to the edges of his fields. And consequently, walls have been built around the fields.

CARVER MCGRIFF: The hedgerows were a virtually perfect defensive way for the Germans to fight the battle, and we had to find a way to get over them or around them.

ADRIAN LEWIS: There was so much focus, so much energy on getting ashore that follow-on tasks, the advance, were not given the attention that they deserve, in terms of figuring out how you need to break through this stuff.

NARRATOR: The battle for the hedgerows consumed the Allies and their resources for much longer than expected.

On D-Day, there were roughly 10,000 Allied casualties. But by the time Normandy was taken, six weeks later, another 200,000 Allied soldiers had been wounded or killed, including McGriff's squad leader.CARVER MCGRIFF: He died while lying next to me. In fact, he tried to talk to me and then was not able. It was a long time ago. The memories don't hurt like they did for a while, but they're always there.

RICK ATKINSON: It's important not to think that once June 6 turns into June 7 that, somehow, the war becomes less intense. The fighting in the hedgerows is as awful, in some cases, as anything that has occurred on Omaha Beach. So the intensity that we see on June 6 is simply a foreshadowing of what's going to come over the next three months in Normandy. 02:35:27

NARRATOR: So what did it take the Allies to win control of Normandy, in terms of men and supplies?

SYLVAIN PASCAUD: One of the things that amazed us the most, I think, was the amount of wrecks we found, the targets. We ended up finding 400 targets during our survey. That's a lot of wrecks.

NARRATOR: The most astounding revelation by the sonar experts inside the Magic Star is the vast majority of those 400 wrecks were sunk after D-Day, revealing the extent of the enormous effort required to reclaim Normandy.

NICK HEWITT: The really exciting thing for me, an historian: we can peel back the water and expose the playbook of Normandy, just like assembling a huge jigsaw puzzle. It's just fascinating.

So, we have evidence when the troops went to shore, and then we have evidence of the support phase that took place for months afterwards. All of that is there.

NARRATOR: Today, the divers have found a barge carrying unusual crossbeam structures, components used to replace bombed-out bridges in France.

The barge was headed to one of the most extraordinary engineering projects of World War II, something designed to make it possible to unload all the necessary gear and men.

It was, in fact, a pet project of British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. In London, just down the street from Churchill's wartime headquarters, is the Institution of Civil Engineers, where evidence still exists of this ambitious plan.

These reams of detailed drawings all resulted from a short, angry memo, written by Churchill himself. That memo got passed along to Tim Beckett's father, Allan, a young military engineer.

TIM BECKETT: My father was working, at the time, in the bridging department of the War Office. Colonel Everall came to him with this memo and said to him, “Beckett, you're a yachtsman, see if you can make something out of this.”

NARRATOR: The memo resulted from a disagreement between President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill about possible locations for the invasion. Churchill was worried that there was no port in Normandy, and, so, these landings could turn into another Dieppe.

His solution was as bold as it was daring. If the Allies couldn't take a port by force, then they would need to build one and take it with them.

TIM BECKETT: It's astonishing, the scale of it and the new organization required.

NARRATOR: Tim Beckett, a port engineer himself, says the plan was astoundingly ambitious. Certainly, the engineering challenges were: no one had ever conceived of building a portable port.

Any port must first provide shelter for ships from the fury of the sea, and it must also have a way to dock and unload the ships. How could they engineer around the notoriously rough seas and changing tides on the coast of France and anchor a port onto the sandy beaches there?

Churchill didn't want to hear about the problems, so he dashed off his short angry memo.

TIM BECKETT: Churchill's memo is very famous. It says: “Piers for use on beaches: They must float up and down with the tide. The anchor problem must be mastered. Let me have the best solution worked out. Don't argue the matter. The difficulties will argue themselves.”

I think you can read into that that Churchill was pretty frustrated, shall we say, when he wrote that. It's a bit terse.

NARRATOR: The challenge of figuring out how to solve these engineering problems fell, in part, to the young Allan Beckett. His initial idea was to build a road that would float up and down with the changing tide. The problem was basic physics: how do you control the movement of a floating road on a rough sea?

TIM BECKETT: Most bridges typically like to have four bearings, and they like their bearings to stay more or less where they are. When you put a floating bridge on, you've got a whole lot of movements. Obviously it's pitching, going up and down, and rolling; then you also have the load going on it as well. Now, you either try to resist that with a rigid structure trying to hold it all together, or you go with it.

NARRATOR: Beckett decided to go with it. He designed a floating road that consisted of pontoons sitting on the water, with roadways, like a bridge, spanning between them.

Another part of the design were massive structures that are still visible today, at low tide, off the coast of Normandy. Like a jetty, these huge concrete blocks were used to hold out the rough sea.

ANDY SHERRELL: See the caissons that are submerged now.

NARRATOR: Seen on sonar, these structures make up some of the largest wrecks off the coast here. But to see what his father created, Tim Beckett goes just outside of Paris, into the world of virtual reality.

NICOLAS SERIKOFF: I think you recognize this place?

TIM BECKETT: I certainly do.

NARRATOR: A French engineering company, called Dassault Systems, has re-created one of these artificial harbors, in 3-D.

TIM BECKETT: We are walking along it. It's as if we could touch it.

NARRATOR: The codename of the project was Mulberry, and so these were known as “Mulberry harbors.” Two harbors were built, one for the Americans, at Omaha Beach, and one British, at the town of Arromanches.

TIM BECKETT: It is really very good.

NICOLAS SERIKOFF: Take your 3-D glasses and we'll jump into the 3-D.

NARRATOR: The basic design of the Mulberry harbors was to create the needed breakwater to block out the rough seas. This was done in two steps: first, old ships were sailed over from England and then dynamited and sunk. Next came massive concrete structures, each the size of a five-story building. They were built in England, pulled across the English Channel.

These massive concrete blocks, called “caissons,” created the jetty that held out the waves.

TIM BECKETT: I think the floating roadways, he was particularly proud of.

NARRATOR: Then came Allan Beckett's roadway that stretched from the beach, over floating pontoons, to piers where ships could dock.

These roadways needed to be strong enough to carry a 33-ton Sherman tank and yet flexible enough to accommodate the water's motion. Engineering around this was the key to Beckett's plan.

TIM BECKETT: You can see that the pontoons are pitching and rolling. The bridges are following it. The bridge spans are not rigid; they can go with the motion. They do it by a rather clever detail. Can we go underneath the bridge?

We've got a rigid connection on the central member here. And all the other ones are pinned, and that's what allows the bridge to twist torsionally.

I always knew it was big, but I think this makes you feel how big it is and how busy it was. It was the busiest port in the world, for a few weeks.

HENRY HENDRIX: There are such things such as war-altering technologies that, once it's revealed that you have that capability, it changes the face of battle. To take an L.S.T., a Landing Ship Tank ship, and land it on the beach and put the ramp down, it would take it ten to 12 hours to offload.

NARRATOR: That's because huge ships have to work around the tides and all of that takes time.

HENRY HENDRIX: When we established the Mulberry harbors, we were able to offload a ship in one hour and 40 minutes.

NARRATOR: And all of this was anchored by a clever system that held the roadways in place, designed by Allan Beckett.

Astonishingly, the first of two massive harbors was functional in only three days after the landings.

But then, not even two weeks after the harbors were built, disaster struck. One of the worst storms of the century blew down hard on the coast of Normandy. The American harbor at Omaha Beach was completely destroyed.

But despite being designed to last only three months, the British Mulberry was in use for nearly 10, during which time it became known as Port Winston, for the man whose angry memo got it built.

In all, two-and-a-half-million men and a half-a-million vehicles passed across these floating roadways. They are just one of the many engineering feats and innovations that helped the Allies prevail in this crucial battle of Normandy.

The seas off the coast of France remained dangerous for months after the landings. The Germans still had control of ports to the east and west of the landing beaches, and so they could send in submarines or drop mines from the air.

NICK HEWITT: All it takes is one aircraft to fly through fast, at night, and drop half-a-dozen pressure mines, and your nice safe passage area is suddenly lethal again.

NARRATOR: Today, the Magic Star crew has found a German U-boat submarine that operated in the English Channel after the landings, finally being sunk in July.