|

|

|

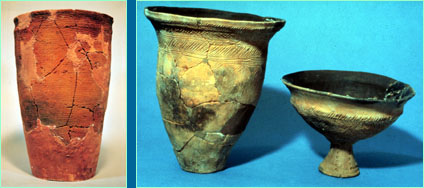

Part 2 | Back to Part 1 Yet the relationship between the Jomon and the Ainu is anything but straightforward. Sometime around A.D. 600 to 700 in Hokkaido, rectangular pit-houses suddenly appear, and a new type of earthenware called "Satsumon" pottery just as precipitately replaced traditional cord-marked pottery. Decorated with incised, geometric patterns, Satsumon pots are quite distinct from those of the preceding Jomon. Their shapes are different, and their walls show evidence of smoothing by pieces of wood having been scraped over the surface. So the Sakushukotoni-gawa site is not a Jomon village. Rather it represents a community of what, after its characteristic pottery, Hokkaido archeologists call the "Satsumon culture." Falling in time between the Jomon and the Ainu, the site is crucial to understanding Ainu development. Rewriting the Ainu Story Having slept fitfully after a nearly 20-hour journey to Sapporo, Hokkaido's capital, I made my way to the lab, where Yoshi took me to a table covered in sample jars. What I saw was not just a few grains of barley, but thousands of charred grains packed into dozens of jars. My Japanese colleagues had recovered the seeds from the initial series of flotation samples from Sakushukotoni-gawa, the first set of such samples ever collected from a Satsumon site. What Yoshi had not told me in that fateful telephone call was that he and his compatriots had only identified a few grains; thousands remained to be analyzed.

Over the next few years, our team examined nearly a quarter million carbonized seeds from Sakushukotoni-gawa. In addition to barley, the samples contained bread wheat, foxtail and broomcorn millet, bean (probably azuki, or Japanese red bean), hemp, rice, melon, and safflower as well as seeds of weeds and wild fruit. We explored many more Satsumon sites on Hokkaido, and all produced crop remains. Sometimes these sites contained only one or two types of grain; others like Sakushukotoni-gawa show a wide range of crops. The list of crops in use on Hokkaido at the time has since expanded to include buckwheat, barnyard millet, and sorghum. The conclusion is inescapable: The Satsumon ancestors of the Ainu were not solely hunter-fisher-collectors. They were farmers. Such a distinction may not sound very significant, but in studies of prehistoric societies, it makes all the difference in shaping a proper understanding of a people's identity, power structure, economy, social relations, and so on. It's as if you were researching your roots and discovered that your ancestors came from South America rather than Europe as you'd always thought; it would change the whole way you thought about your family history.

The general archeological record in Japan is consistent with this view. Starting about 400 B.C., the Jomon in southwestern Japan had given way to strong influences from China and Korea, including migration. Eight hundred to a thousand years later, most of Japan excluding Hokkaido had made a significant commitment to agriculture. This period (400 B.C. to A.D. 300) was the time of the Yayoi, a rice-farming culture named after the first site of its kind, which was discovered in Tokyo's Yayoi neighborhood. While known for being the first group in Japan to use irrigated rice fields for intensive food production, the Yayoi also grew other crops, including barley, wheat, and foxtail and broomcorn millet. In northeastern Japan, where attempts to grow rice met with little success, these other crops flourished. All the crops found in Satsumon Hokkaido were likely growing by A.D. 400-500 in Tohoku, the northernmost province of Honshu, Japan's main island that lies just to the south of Hokkaido. Continue: Hokkaido Jomon cultures continued during the Yayoi period Origins of the Ainu | Ainu Legends | Find Your Way Resources | Transcript | Site Map Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule About NOVA | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Jobs | Search | To print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated November 2000 |

An early Jomon pot (left) and later Satsumon pottery.

An early Jomon pot (left) and later Satsumon pottery.

An archeological team works on an early Satsumon

house on Hokkaido.

An archeological team works on an early Satsumon

house on Hokkaido.

An electron microscope image of a grain of barley

from the Sakushukotoni-gawa site on Hokkaido.

An electron microscope image of a grain of barley

from the Sakushukotoni-gawa site on Hokkaido.