|

|

|

|

1. Resting on a sled that moved over rollers, the

giant obelisk was pulled to the edge of a steep ramp.

1. Resting on a sled that moved over rollers, the

giant obelisk was pulled to the edge of a steep ramp.

|

First Attempt

by Rob Meyer

In 1995, a NOVA team dared to demonstrate firsthand what has

mystified historians for millennia: how to raise an obelisk

using only materials and techniques the ancient Egyptians

might have used. Archaeologist

Mark Lehner

relied on scholarship to investigate these materials and

techniques.

Roger Hopkins,

an expert stonemason, pushed the group forward with an

unyielding optimism and a keen knowledge of the granite that

they were to work with. The late Aly el Gasab, one of Egypt's

foremost specialists in moving heavy statues, brought his vast

experience to the project and motivated the hundreds of

Egyptian workers who struggled to accomplish this monumental

task. Finally, Martin Isler, a sculptor and graphic artist

with a passion for stonework, provided his own theories and

tried to keep the team's ideas realistic.

2. Once the obelisk began to pivot over the edge,

three braking ropes attached to the monument's tip

were pulled taut to control the fall. Were the ropes

to fail, the granite obelisk would violently smash

against the ground and crack.

2. Once the obelisk began to pivot over the edge,

three braking ropes attached to the monument's tip

were pulled taut to control the fall. Were the ropes

to fail, the granite obelisk would violently smash

against the ground and crack.

|

|

The first challenge was to secure an obelisk, which the

ancients traditionally sculpted from a single piece of granite

carved from quarries in Aswan. Lehner sought hints about

ancient quarrying at the so-called Unfinished Obelisk, a

monolith that some unidentified pharaoh abandoned after

structurally dangerous cracks appeared during its removal.

Other evidence suggests that ancient laborers pounded away the

surrounding granite with round hammers of dolorite, which is

harder than granite. Foremen likely assigned small "working

patches" to each laborer, who would spend months or possibly

even years chipping away at the hard granite. It was not long

before Roger Hopkins, the stonemason, realized that, if the

team wanted an obelisk anytime soon, it needed a shortcut. The

crew then brought in bulldozers and other modern machinery,

which quickly quarried a large obelisk for the NOVA team.

|

3. Once in place, the obelisk was removed from its

sled and gently fell right into the turning groove.

3. Once in place, the obelisk was removed from its

sled and gently fell right into the turning groove.

|

Before trying to raise the new obelisk, the team explored a

number of issues surrounding these sculptural wonders. How did

the ancients transport them from the quarries at Aswan to

Thebes and other New Kingdom capitals farther down the Nile?

The polished sides and beautifully carved hieroglyphs of

existing obelisks were examined for clues. Using model boats,

team members traded theories on how the pharaohs' engineers

placed these gargantuan monuments, which could weigh up to 440

tons, onto boats and shipped them down the Nile. Finally,

Martin Isler lead the team in successfully raising a smaller,

two-ton obelisk using a levering technique.

4. Pushing down on a lever placed under the obelisk

and pulling on a rope fixed to its tip proved futile.

Once the angle became too steep, the lever became too

high for the men to effectively use it. The pulling

rope only pushed the obelisk down into the turning

groove.

4. Pushing down on a lever placed under the obelisk

and pulling on a rope fixed to its tip proved futile.

Once the angle became too steep, the lever became too

high for the men to effectively use it. The pulling

rope only pushed the obelisk down into the turning

groove.

|

|

After some delay, the large obelisk was ready for raising.

Tensions mounted as each member of the team advanced his own

theory as to how to raise it. Isler felt levering alone could

do the trick. Another proposed technique called for a giant

counterweight, attached to the bottom of the obelisk, that

would swing the shaft up like a seesaw. Hopkins was convinced

the answer lay in building a great earthen ramp up to a

specially designed chamber containing sand. In this scenario,

laborers would carefully tip the base of the obelisk into the

top of the chamber, then begin removing sand from a trap door

in the chamber's base. When the obelisk reached a pedestal at

the bottom of the chamber, team members would ease one edge of

its base into a so-called "turning groove," which would hold

the obelisk in position as other laborers pulled it upright.

|

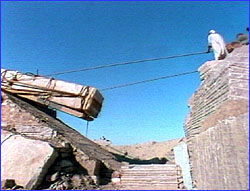

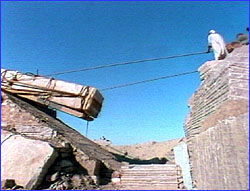

Aly el Gasab skillfully directed the Egyptian crew

that carefully lowered the pillar down the ramp and

into the turning groove.

Aly el Gasab skillfully directed the Egyptian crew

that carefully lowered the pillar down the ramp and

into the turning groove.

|

The team agreed to adopt the ramp technique but decided that

sand was not dependable. Instead, it was the vision of Aly el

Gasab that drove the final stage. First, the crew put the

obelisk on a sled and hauled it on rollers up the ramp. Once

it began to pivot over the top edge of the ramp, workers

yanking down on ropes fixed to its top controlled its descent

down another, steeper ramp into the turning groove.

So far so good. The obelisk then rested at a 32-degree angle

from the ground. Workers with levers quickly forced it up to

about 40 degrees—nearly halfway to success. Once at this

angle, however, the team proved unable to get the leverage

necessary to raise the obelisk the rest of the way. Workers

redoubled their efforts, pulling hard at ropes fixed to the

obelisk's tip. But this simply forced the shaft's butt end

deeper into the turning groove. As the sun passed the horizon,

they realized with a shudder that they had but one more

day.

Roger Hopkins ran the pulling rope over an A-frame to

give the pullers a mechanical advantage.

Roger Hopkins ran the pulling rope over an A-frame to

give the pullers a mechanical advantage.

|

|

Early the next morning, Hopkins set up a large A-frame, over

which he ran the rope tied to the tip of the obelisk. By

adjusting the angle of the rope in this way, he hoped to give

the pullers a mechanical advantage: Now they were essentially

pulling up rather than down. Alas, this last-ditch effort

proved futile. The ropes on the pullers' side of the A-frame

angled down too steeply for enough workers to reach them.

Another ramp was needed—one whose angle matched that of

the rope—but time had run out.

|

5. In an eleventh-hour effort, the rope was run over

an A-frame in order to give more lift to its pull.

Unfortunately, this resulted in the rope being too

high for the pullers to reach, and the obelisk never

was raised beyond 42 degrees.

5. In an eleventh-hour effort, the rope was run over

an A-frame in order to give more lift to its pull.

Unfortunately, this resulted in the rope being too

high for the pullers to reach, and the obelisk never

was raised beyond 42 degrees.

|

While unsuccessful in meeting their goal, the team members had

learned much from their efforts—knowledge that they will

apply during their

second chance

to raise an obelisk.

Rob Meyer is Production Assistant of NOVA Online.

Explore Ancient Egypt

|

Raising the Obelisk |

Meet the Team

Dispatches |

Pyramids |

E-Mail |

Resources

Classroom Resources

| Site Map |

Mysteries of the Nile Home

Editor's Picks

|

Previous Sites

|

Join Us/E-mail

|

TV/Web Schedule

About NOVA |

Teachers |

Site Map |

Shop |

Jobs |

Search |

To print

PBS Online |

NOVA Online |

WGBH

©

| Updated November 2000

|

|

|

1. Resting on a sled that moved over rollers, the

giant obelisk was pulled to the edge of a steep ramp.

1. Resting on a sled that moved over rollers, the

giant obelisk was pulled to the edge of a steep ramp.

2. Once the obelisk began to pivot over the edge,

three braking ropes attached to the monument's tip

were pulled taut to control the fall. Were the ropes

to fail, the granite obelisk would violently smash

against the ground and crack.

2. Once the obelisk began to pivot over the edge,

three braking ropes attached to the monument's tip

were pulled taut to control the fall. Were the ropes

to fail, the granite obelisk would violently smash

against the ground and crack.

3. Once in place, the obelisk was removed from its

sled and gently fell right into the turning groove.

3. Once in place, the obelisk was removed from its

sled and gently fell right into the turning groove.

4. Pushing down on a lever placed under the obelisk

and pulling on a rope fixed to its tip proved futile.

Once the angle became too steep, the lever became too

high for the men to effectively use it. The pulling

rope only pushed the obelisk down into the turning

groove.

4. Pushing down on a lever placed under the obelisk

and pulling on a rope fixed to its tip proved futile.

Once the angle became too steep, the lever became too

high for the men to effectively use it. The pulling

rope only pushed the obelisk down into the turning

groove.

Aly el Gasab skillfully directed the Egyptian crew

that carefully lowered the pillar down the ramp and

into the turning groove.

Aly el Gasab skillfully directed the Egyptian crew

that carefully lowered the pillar down the ramp and

into the turning groove.

Roger Hopkins ran the pulling rope over an A-frame to

give the pullers a mechanical advantage.

Roger Hopkins ran the pulling rope over an A-frame to

give the pullers a mechanical advantage.

5. In an eleventh-hour effort, the rope was run over

an A-frame in order to give more lift to its pull.

Unfortunately, this resulted in the rope being too

high for the pullers to reach, and the obelisk never

was raised beyond 42 degrees.

5. In an eleventh-hour effort, the rope was run over

an A-frame in order to give more lift to its pull.

Unfortunately, this resulted in the rope being too

high for the pullers to reach, and the obelisk never

was raised beyond 42 degrees.